Aristotle’s enduring insights reveal a paradox at the heart of power: societies rarely elevate the wisest or most capable, but instead choose leaders who feel safe, familiar, and compatible. Practical wisdom (phronesis) teaches that virtue lies in balance, yet power consistently favors stability over excellence, comfort over truth. The truly brilliant often remain in the shadows, either rejected as threats or forced to dilute their vision into palatable simplicity. Leaders, more often symbols than originators, act as shock absorbers who preserve continuity while unseen forces script decisions behind the curtain. From politics to business, charisma and conformity outshine competence, as emotional resonance outweighs rational debate. The path forward lies not in lamenting mediocrity but in cultivating phronesis within ourselves and our communities, redefining leadership as service, integrity, and empowerment—where true change begins.

Aristotle’s Enduring Insights: Why Practical Wisdom Rarely Reaches the Seat of Power

I. Introduction: The Puzzle of Power and Practical Wisdom

Intended Audience and Purpose

This article is written for leaders, professionals, educators, thinkers, and concerned citizens who find themselves puzzled—or perhaps frustrated—by the paradox of leadership in society. Why do we so often see mediocrity rise while brilliance remains in the shadows? Why are communities, corporations, and nations led by those who are safe rather than those who are wise?

The purpose here is not to moralize or lament but to examine Aristotle’s timeless insights into phronesis—practical wisdom—and use them as a lens to understand why human societies consistently prioritize familiarity, stability, and comfort over brilliance, vision, and excellence.

A. Aristotle’s Distinctive Legacy

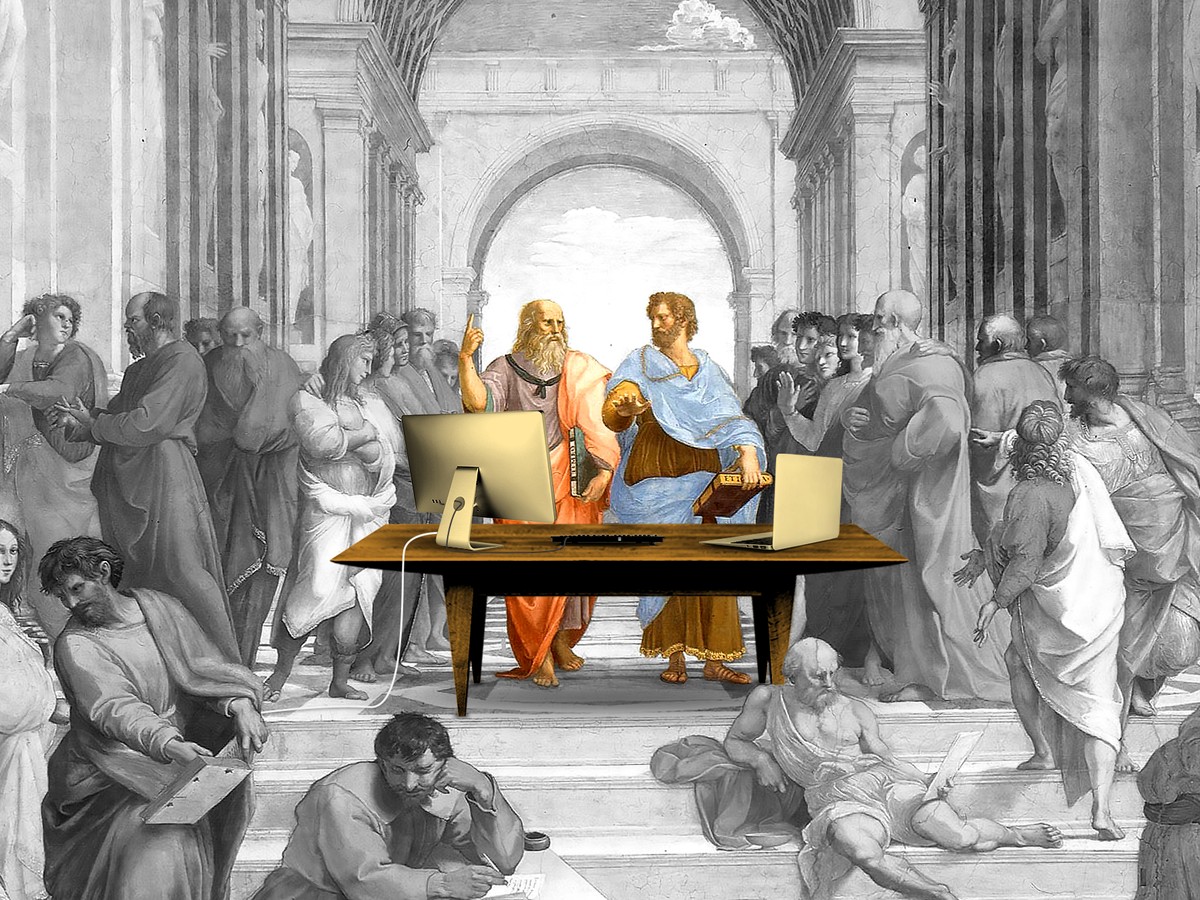

Among the great thinkers of antiquity, Aristotle occupies a special place—not for being the most abstract, but for being the most grounded. Where Plato often speculated about ideals and metaphysical forms, Aristotle asked how human beings could actually live well in the here and now. His philosophy was never meant to be an ivory-tower exercise; it was a manual for human flourishing (eudaimonia).

Aristotle concerned himself with the choices people make, the habits they form, and the ways communities can organize themselves to promote a meaningful life. In short, he sought not just truth but usefulness—how to apply reason to the messiness of everyday living. That is why, two millennia later, his observations about wisdom, virtue, and leadership still feel startlingly fresh.

B. The Golden Mean: Balance, Not Extremes

At the core of Aristotle’s ethical thought lies the idea of the Golden Mean—the belief that virtue is found not in extremes but in balance. Every quality, he argued, exists on a spectrum: courage, for example, lies between cowardice (too little) and recklessness (too much). Generosity lives between stinginess and wastefulness. Even honesty must be tempered, existing between deceit on one side and brutal candor on the other.

This pursuit of balance was not just a personal ethic but a guiding principle for governance and leadership. A society thrives not when pushed to extremes, but when its leaders embody measured judgment—choosing neither reckless upheaval nor paralyzing caution, but something in between. Practical wisdom, therefore, is not about knowing abstract truths but about discerning the right measure in concrete situations.

C. Setting Up the Central Paradox

Here, however, emerges the puzzle. If wisdom and virtue are indeed the highest goods, why do the best among us so rarely rule? Why are societies not led by their most virtuous, capable, or insightful individuals?

Aristotle’s unsettling answer is that power does not naturally gravitate toward excellence. Instead, it selects for stability, familiarity, and reassurance. Leaders rise not because they embody the highest wisdom, but because they fit the collective’s instinct for survival and continuity.

This is the paradox that haunts every age: the wisest often remain in the shadows while the stage is occupied by those who are acceptable, relatable, and safe. To understand why requires us to look beyond ideals of merit and into the deeper instincts of human communities—a journey we will now take with Aristotle as our guide.

II. Why the Best Rarely Rule: Aristotle’s Anatomy of Power

If wisdom and virtue represent the highest human achievements, one might expect society to naturally elevate its best and brightest into positions of authority. Yet history tells a different story. Time and again, we see the wise overlooked, the brilliant rejected, and the truly virtuous sidelined in favor of leaders who feel familiar, relatable, or merely “safe.” Aristotle recognized this paradox long before modern democracies or corporate hierarchies. His analysis offers a sobering reminder: leadership is less about excellence and more about compatibility with the instincts of the collective.

A. Competence vs. Comfort

The uncomfortable truth is that people rarely choose leaders on the basis of competence alone. Instead, they gravitate toward those who make them feel comfortable—leaders who resemble them, who reinforce their worldview, or who offer the illusion of stability.

A supremely capable individual may be brilliant in vision and execution, but if they unsettle the group, they are unlikely to gain trust. Leadership, then, is not simply about solving problems; it is about soothing anxieties. In this sense, the “best” do not always rise, because society prizes reassurance over raw ability.

B. Society as an Organism

Aristotle often described society as a living body, where every part has its function. Within this metaphor, the leader is not the “brain” that generates ideas but the “heart” that maintains rhythm. The heart does not innovate or strategize—it keeps the organism alive.

From this perspective, the leader’s primary role is not brilliance but survival. A leader succeeds when they prevent collapse, hold a group together, and maintain a steady beat, even if they are not the sharpest mind in the room. In moments of crisis, society instinctively seeks not the most original thinker but the figure who can keep the pulse going. Power, therefore, serves continuity, not creativity.

C. The Fear of the Extraordinary

The greatest irony of leadership is that those with extraordinary vision often become threats to the very people they wish to serve. Radical thinkers and reformers appear destabilizing because they move too far, too fast. Their brilliance, instead of inspiring, unsettles.

History offers ample examples: Socrates was condemned for “corrupting the youth” with his relentless questioning. Prophets across traditions were ignored, resisted, or persecuted for challenging established norms. Innovators from Galileo to Tesla encountered ridicule or rejection before their insights were accepted—often long after their deaths.

Aristotle recognized this instinct for self-preservation: societies fear leaders who outpace them, preferring instead those who move incrementally within familiar bounds. In other words, brilliance threatens order, and order almost always wins.

D. The Compatibility Principle

Aristotle captured this dynamic in a simple but profound observation: “The best regime is the one that fits its people.”

The operative word here is “fits.” Leadership, in this sense, is not about elevating the most excellent but about selecting the most compatible. A good leader, according to this view, is not the one who pushes a society toward ideals it cannot yet embrace but the one who mirrors its current identity, values, and pace of change.

This explains why leaders often look like reflections of their societies: they embody prevailing cultural norms more than they challenge them. They succeed not by being exceptional outliers but by being familiar enough to represent “one of us.”

E. Persuasion Mechanics

Aristotle also dissected the mechanics of persuasion, a skill central to leadership. He identified three pillars:

- Logos (reason and logic),

- Ethos (credibility and character), and

- Pathos (emotion).

While logic (logos) may seem like the strongest foundation, Aristotle observed that most decisions—especially collective ones—are shaped by ethos and pathos. People respond to trust, credibility, and emotional resonance far more readily than to complex reasoning.

This remains true in both politics and business today. Campaigns are won not by the most rational policies but by the most relatable narratives. Managers rise not by demonstrating brilliance but by projecting reliability and cultural fit. Humans prefer belonging over being right, reassurance over innovation. The leader who feels familiar, who speaks to our hearts, will almost always triumph over the one who only appeals to our minds.

Aristotle’s anatomy of power forces us to rethink leadership in unsettling ways. It suggests that the system is not “broken” when mediocrity prevails; rather, it is functioning exactly as designed—to preserve survival through stability, even at the cost of brilliance.

III. The Fate of the Truly Capable

If the most competent minds rarely ascend to power, where do they go? Aristotle’s framework offers both a sobering and liberating answer. The truly capable often step away from the messy compromises of politics and hierarchy—not out of weakness, but because their pursuit lies elsewhere. They seek eudaimonia: a flourishing life rooted in self-mastery, creativity, and the cultivation of wisdom. Their fate, then, is paradoxical. They may never rule, but they often shape the world in deeper, more lasting ways than rulers ever could.

A. Excellence Redirected: Pursuing Eudaimonia

Aristotle’s highest human good was not dominance but flourishing—eudaimonia. This flourishing is not passive happiness but active engagement in living well, thinking deeply, and creating meaning. The truly capable person recognizes that political power demands endless compromise: bargaining with mediocrity, appealing to base instincts, and trading clarity for consensus. For the wise, these are distractions. Their energy is better invested in cultivating virtue, advancing knowledge, or perfecting their craft.

Thus, philosophers, scientists, artists, and reformers often redirect their brilliance into creating legacies beyond the reach of kings or presidents. Power is temporary; wisdom and innovation, when translated into culture, endure.

B. Brilliance as a Threat

Yet brilliance carries its own burden. To the crowd, the visionary does not always inspire confidence but suspicion. Aristotle’s insight was blunt: extraordinary individuals unsettle the ordinary fabric of society. A radical thinker appears unrelatable, even dangerous, because their horizon stretches far beyond the present.

History is littered with examples. Socrates was condemned for “corrupting the youth.” Galileo was forced to recant truths about the cosmos. Innovators like Tesla died in obscurity while safer, more palatable figures reaped rewards. To be brilliant is often to be misinterpreted, caricatured, or dismissed as eccentric—proof that genius, without translation, risks alienation.

C. The Self-Limiting Act

Those rare visionaries who manage to gain influence usually succeed not by dazzling with complexity, but by simplifying. They practice what could be called the “translation act”: distilling profound ideas into digestible narratives. Aristotle’s own works, often written as lecture notes for students, demonstrate this balance—layered with rigor yet accessible enough to instruct.

But this translation comes at a cost. The capable must dilute nuance, round off sharp insights, and sometimes conceal the radical implications of their thought. They trade raw brilliance for relatability, authenticity for influence. It is a compromise that explains why the legacies of great leaders are often remembered in fragments—half-truths and slogans rather than the full depth of their vision.

And so the fate of the truly capable is bittersweet: to flourish in the private realm, to shape posterity indirectly, or to step into the public square only after trimming their brilliance into a language the many can accept.

IV. Idiots in Power? The System’s Hidden Logic

The lament that “idiots are running the world” is a sentiment as old as politics itself. Aristotle, with his disarming realism, would neither fully disagree nor entirely affirm it. The so-called “idiots in power” are less anomalies than predictable outcomes of the way societies organize themselves. Power is rarely about selecting the most capable; it is about ensuring stability, continuity, and reassurance. To understand this, we must look not at leadership as a failure of wisdom, but as a hidden survival mechanism built into the system itself.

A. Leaders as Shock Absorbers

Leadership, in Aristotle’s anatomy of power, often functions less like a guiding intellect and more like a stabilizing organ. Leaders cushion disruption, slow down change, and project a sense of order—even when chaos is brewing underneath. In this sense, the “idiot” leader, who offers platitudes instead of vision, serves a function: keeping the collective pulse steady. They reassure the public that the world tomorrow will look familiar enough to prevent panic.

Seen this way, the presence of uninspired leaders is not accidental—it is the immune system of society working to prevent shock.

B. Leadership as Theater

Power is not just functional; it is theatrical. Aristotle noted how rhetoric—logos, ethos, and pathos—often outweighed truth in persuasion. In modern terms, leaders are the front-stage actors of an elaborate performance. The real scripts are often written backstage by donors, advisors, strategists, or interest networks.

The leader’s role, then, is less to originate than to symbolize. They embody the values, myths, and anxieties of their people. Their speeches are less about instruction than reassurance, less about originality than resonance. This explains why charismatic “performers” often rise higher than brilliant but awkward truth-tellers.

C. The Stability Bias

The system is biased toward predictability, even at the expense of excellence. Societies, like organisms, prefer steady survival to risky brilliance. Brilliance disrupts; mediocrity stabilizes.

This comes at a cost. Mediocre leaders may preserve stability, but they also slow down innovation, postpone necessary reforms, and entrench stagnation. Delayed responses to crises—from climate change to economic inequality—are the natural byproduct of this bias. It is not that leaders are ignorant; it is that the system rewards delay over daring.

D. Comfort Before Truth

Ultimately, societies do not place truth at the top of their priority list. Continuity comes first. Leaders who embody continuity, however uninspired, are more likely to rise than those who challenge the comfortable fabric of life with inconvenient truths.

From an evolutionary perspective, this is not a flaw but a feature. Societies that constantly embraced radical change would collapse under the weight of perpetual upheaval. The trade-off, however, is that comfort is purchased at the expense of progress. The system ensures survival, but it often sidelines excellence.

V. Modern Implications: Aristotle in the Age of Politics and Business

Aristotle may have written in the polis of ancient Athens, but his insights into power feel eerily current. The dynamics he described—comfort over brilliance, stability over vision, ethos and pathos over logos—play out with precision in our corporations, governments, and even our online spaces. The puzzle of power he outlined has not disappeared; it has simply upgraded its tools.

A. Corporate Patterns

In today’s organizations, promotion often favors the likable manager over the disruptive innovator. HR policies and executive committees speak of valuing innovation, but when decisions are made, the safer bet usually wins. “Culture fit” becomes the euphemism for predictability—an employee who doesn’t threaten the company’s existing order.

Aristotle’s “compatibility principle” is alive and well here: the best leader is not the one with the boldest ideas, but the one who blends most comfortably into the organization’s identity. The result? Many innovators leave to build startups, while middle managers climb the ladder by being agreeable rather than transformative.

B. Populist Politics

The political stage mirrors this logic on a larger scale. Charisma consistently outshines competence. Politicians who master the art of emotional connection—handshakes, slogans, soundbites—often sweep past rivals with deeper policy expertise. Popularity, not practicality, becomes the ultimate currency.

This is not new. Aristotle himself warned that rhetoric could bend crowds more effectively than truth. But modern mass media has intensified the effect. Campaigns are no longer battles of reasoned policy but contests of storytelling and personality.

C. Social Media and Influence

If politics is theater, social media is its global stage. Platforms amplify Aristotle’s ethos and pathos while marginalizing logos. Emotional resonance—anger, outrage, inspiration—travels farther and faster than rational argument. A single viral video of a politician hugging a child carries more influence than a 200-page policy document.

This algorithmic bias doesn’t just reward emotional leaders; it reshapes leadership itself. Leaders increasingly curate personas designed to maximize relatability and visibility, not necessarily substance. Aristotle’s warnings about persuasion mechanics could be republished as a manual for social media strategy today.

D. Education and Leadership Development

The problem runs deeper than business and politics. Our education and leadership systems often reinforce conformity rather than cultivating wisdom. Schools reward compliance and standardized performance. Leadership programs focus on strategy and communication skills, but rarely on phronesis—the integration of ethics, judgment, and lived wisdom.

What results are leaders who know how to maintain systems, but not how to question them. The missing ingredient is precisely what Aristotle saw as indispensable: practical wisdom rooted in virtue. Reviving phronesis—in classrooms, boardrooms, and political training grounds—may be the only sustainable antidote to the mediocrity trap.

VI. Conclusion: Reconceptualizing Leadership and Responsibility

A. The Unsettling Truth

Aristotle’s sobering insight still rings true: power does not reliably select for excellence. It selects for compatibility. Leaders are chosen not because they embody the best of human potential, but because they fit the expectations, anxieties, and rhythms of their societies. The very structure of power rewards familiarity and reassurance more than vision or brilliance.

B. History’s Endless Repetition

This explains why mediocrity in leadership is not an exception but a recurring pattern across cultures and centuries. From ancient Athens to modern democracies, from medieval courts to corporate boardrooms, the script repeats: those who comfort are elevated, those who challenge are sidelined, and those who dare to stretch the horizon too far are cast as dangerous.

C. The Real Question: Who Writes the Script?

If leaders are actors—symbols on a stage—then the deeper question is not why they are mediocre, but who is directing the play. Who benefits from stability over disruption? Whose interests are served by slowing change, cushioning shock, and projecting continuity? By following this line of inquiry, responsibility shifts from blaming “idiots in power” to recognizing the networks—economic, cultural, institutional—that script their roles.

D. Actionable Reflection

If mediocrity is the system’s default, then the antidote must come from outside the system. Citizens, educators, professionals, and entrepreneurs must shoulder the responsibility of cultivating phronesis—practical wisdom grounded in ethics, balance, and courage. Leadership, reconceptualized, is not about dominance or status, but about service: the capacity to guide, to empower, and to act with integrity in the face of complexity.

True leadership, then, may not come from those who hold formal power, but from individuals and communities who live by wisdom and example. The question is less “Who rules?” and more “How do we live, act, and lead in ways that resist mediocrity?”

E. Participate and Donate to MEDA Foundation

At MEDA Foundation, our work begins from this very principle: that leadership is service, and service is the soil from which true communities grow. We are committed to creating ecosystems where wisdom, compassion, and self-sufficiency thrive. From supporting autistic individuals to building inclusive employment pathways, our mission is to empower people to help themselves—and in doing so, redefine what leadership looks like.

If you believe leadership must evolve beyond mediocrity, we invite you to participate, collaborate, and support our mission. Your donations and involvement directly fuel projects that embody phronesis in action—practical wisdom lived out in the service of others. True leadership begins not in palaces or boardrooms, but in communities where dignity and self-reliance are nurtured.

Book References

- Aristotle – Nicomachean Ethics

- Aristotle – Politics

- Martha Nussbaum – The Fragility of Goodness

- Jonathan Lear – Aristotle: The Desire to Understand

- Hannah Arendt – The Human Condition