Freedom is humanity’s greatest achievement and its gravest responsibility: when rightly used, it safeguards autonomy, dignity, and progress; when misused, it corrodes trust and neglects duty; when abused, it becomes a weapon that undermines rights themselves. True liberty requires the inseparable companion of responsibility, distinguishing the self-chosen limits of conscience from coercion, and protecting society through the harm principle rather than paternalistic overreach. In the modern age, especially in digital spaces, balancing individual rights with accountability is essential to prevent manipulation, exploitation, and authoritarian control. The enduring challenge for every generation is not only to inherit freedom but to actively preserve and renew it through responsible action—ensuring liberty remains a tool for human flourishing rather than its undoing.

ಸ್ವಾತಂತ್ರ್ಯ ಮಾನವತೆಗೆ ಪಡೆದಿರುವ ಮಹತ್ತಮ ಸಾಧನೆಯಾಗಿಯೇ ಅಲ್ಲ, ಅದರಿಂದ ಬರುವ ಅತ್ಯಂತ ಭಾರೀ ಹೊಣೆಗಾರಿಕೆಯೂ ಆಗಿದೆ: ಸರಿಯಾಗಿ ಬಳಸಿದಾಗ, ಅದು ಸ್ವಾಯತ್ತತೆ, ಗೌರವ ಮತ್ತು ಪ್ರಗತಿಯನ್ನು ರಕ್ಷಿಸುತ್ತದೆ; ದುರ್ಬಳಕೆಯಾದಾಗ, ಅದು ನಂಬಿಕೆಯನ್ನು ಕುಗ್ಗಿಸುತ್ತದೆ ಮತ್ತು ಕರ್ತವ್ಯವನ್ನು ನಿರ್ಲಕ್ಷಿಸುತ್ತದೆ; ದುರುಪಯೋಗವಾದಾಗ, ಅದು ಹಕ್ಕುಗಳನ್ನು ಧ್ವಂಸ ಮಾಡುವ ಆಯುಧವಾಗುತ್ತದೆ. ನಿಜವಾದ ಸ್ವಾತಂತ್ರ್ಯಕ್ಕೆ ಹೊಣೆಗಾರಿಕೆ ಅವಿಭಾಜ್ಯ ಸಂಗಾತಿಯಾಗಿದೆ, ಅದು ಆತ್ಮಚೇತನದಿಂದ ಆಯ್ದ ಮಿತಿಗಳನ್ನು ಬಲಾತ್ಕಾರದಿಂದ ವಿಭಿನ್ನವಾಗಿ ಗುರುತಿಸುತ್ತದೆ ಮತ್ತು ಪಿತೃತ್ವದ ಅತಿರೇಕವಿಲ್ಲದೆ ಹಾನಿ ತತ್ತ್ವದ ಮೂಲಕ ಸಮಾಜವನ್ನು ರಕ್ಷಿಸುತ್ತದೆ. ವಿಶಿಷ್ಟವಾಗಿ ಡಿಜಿಟಲ್ ಕ್ಷೇತ್ರಗಳಲ್ಲಿ, ವೈಯಕ್ತಿಕ ಹಕ್ಕುಗಳು ಮತ್ತು ಜವಾಬ್ದಾರಿಯ ನಡುವಿನ ಸಮತೋಲನವನ್ನು ಕಾಯ್ದುಕೊಳ್ಳುವುದು ಅತ್ಯವಶ್ಯಕ, ಇದರಿಂದ ದುರುಪಯೋಗ ಮತ್ತು ಅಧಿಕಾರದ ಅತ್ಯಾಚಾರವನ್ನು ತಡೆಯಬಹುದು. ಪ್ರತಿ ತಲೆಮಾರಿನ ಸವಾಲು ಎಂದರೆ ಸ್ವಾತಂತ್ರ್ಯವನ್ನು ಮಾತ್ರ ಸ್ವೀಕರಿಸುವುದಲ್ಲ, ಅದನ್ನು ಸಕ್ರಿಯವಾಗಿ ಕಾಪಾಡಿ, ಹೊಣೆಗಾರಿಕೆಯಿಂದ ನವೀಕರಿಸುವುದಾಗಿದೆ—ಹೀಗಾಗಿ ಸ್ವಾತಂತ್ರ್ಯ ಮಾನವನ ಅಭಿವೃದ್ಧಿಗೆ ಮಾರ್ಗದರ್ಶಕವಾಗಿರಲಿ, ನಾಶಕವಲ್ಲ.

The Imperative of Responsible Liberty: Using Freedom, Avoiding Misuse and Abuse

I. Introduction: Freedom’s Paradox

A. Freedom as Humanity’s Crown and Burden

Liberty has always stood as the crown jewel of human aspiration. From ancient struggles against tyrants to modern campaigns for civil rights, the cry for freedom has united people across cultures and centuries. To be free is to live with dignity, to shape one’s destiny, and to act without the shadow of arbitrary control. But liberty is not only humanity’s crown—it is also its heaviest burden.

The paradox is stark and unrelenting. When freedom is exercised without responsibility, it unravels into chaos, selfish indulgence, and even violence. History is filled with examples: revolutions that began in the name of liberty but descended into bloodshed when individuals mistook liberty for licence. On the other hand, when freedom is overregulated—smothered under paternalistic laws or authoritarian control—it suffocates human creativity, initiative, and the spirit of dissent that drives progress.

This tension leaves us with an enduring challenge: how can we use freedom wisely without misusing or abusing it? To live free is to live in balance—between autonomy and accountability, between the individual and the collective, between expression and restraint. The vitality of freedom lies not in its existence alone but in the discipline with which it is practiced.

B. Philosophical Anchors

Philosophers through the ages have wrestled with this balance. Four perspectives stand out as guideposts for our discussion.

- Mill’s Harm Principle

John Stuart Mill, in On Liberty (1859), offered perhaps the clearest line in the sand: freedom extends until it inflicts harm on others. A person’s speech, choices, or actions may be eccentric, unpopular, or even offensive, but as long as they do not cause real injury—whether physical, psychological, or material—they should not be curtailed. This principle remains a cornerstone in liberal democracies, though its application grows increasingly complex in the digital age, where the boundaries of “harm” are blurred. - Berlin’s Dual Freedoms

Isaiah Berlin deepened the conversation by distinguishing between negative liberty (freedom from interference) and positive liberty (freedom to self-determination). Negative liberty protects us from oppressive external forces, while positive liberty emphasizes the internal resources and conditions needed to exercise choice meaningfully. A starving person may technically be “free” to seek food, but without access or opportunity, that freedom is hollow. Berlin’s insight compels us to see freedom not as a single entity but as a dynamic interplay of protection and empowerment. - Aristotle’s Warning

Centuries earlier, Aristotle cautioned that liberty detached from virtue quickly degenerates into licence. In his political philosophy, true freedom is inseparable from moral character; a society of undisciplined individuals cannot remain free for long. This ancient wisdom reminds us that liberty is not merely about rights—it is equally about cultivating habits of responsibility, moderation, and justice. - The Modern View: Sen & Nussbaum

Contemporary thinkers like Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum extend the conversation by framing freedom as capability. To be free is not merely to be unshackled from coercion; it is to possess the real power to live a valued life. This view connects liberty with social justice: freedom is shallow if people lack education, health, or economic security. Thus, sustaining freedom demands not just legal guarantees but also the creation of social conditions that allow people to use it meaningfully.

Together, these anchors form a prism through which we can examine liberty. Freedom is not a monolith but a spectrum: protection against domination, empowerment for self-realization, discipline through virtue, and capability for flourishing.

C. Intended Audience & Purpose

This article is written for a wide yet connected audience:

- Students, who must learn that freedom is not indulgence but disciplined self-expression.

- Citizens, who must practice liberty in daily life while respecting the rights of others.

- Policymakers, tasked with drawing boundaries that protect freedom without strangling it.

- Educators, entrusted with cultivating civic virtue and moral reasoning in the next generation.

- Community leaders, who carry the responsibility of guiding collective freedom toward harmony and progress.

The purpose is clear: to illuminate how freedom can be sustained only when its legitimate use is distinguished from its misuse through neglect and its abuse through harm. By exploring these distinctions, we aim to show that liberty’s survival is not guaranteed by laws alone but by the wisdom, restraint, and courage with which individuals and societies wield it.

II. The Legitimate Use of Freedom

A. Negative Liberty: Shielding the Individual

The first and most widely recognized face of freedom is negative liberty—the absence of external interference. At its core, this form of liberty asserts that individuals must have a protected sphere of life where neither the state, nor society, nor any authority can dictate their choices. It is the right to live uncoerced.

Classic examples illustrate its value. The freedom of privacy shields citizens from invasive surveillance; religious liberty allows individuals to practice or reject faith without coercion; the freedom to dissent guarantees that unpopular or minority voices can challenge the prevailing order. These rights are not luxuries—they are safeguards against tyranny.

Yet, thinkers in the republican tradition refine this idea further. For them, freedom is not merely non-interference but non-domination. A person might live without interference from a master, but if that master retains arbitrary power over them, the person is not truly free. Immunity from domination—not just the absence of meddling—is what secures genuine liberty. This insight is crucial in today’s world, where institutions, corporations, and even algorithms can shape lives invisibly, exercising control without overt coercion.

B. Positive Liberty: Empowerment and Agency

While negative liberty protects against intrusion, it does not guarantee the ability to act meaningfully. This is where positive liberty enters the discussion. It is the freedom to—the capability and resources needed to make choices that matter.

Positive liberty is not about paternalistic control; rather, it is about empowerment. A person cannot be said to be free if they lack food, education, or access to justice, even if no one is actively obstructing them. Freedom requires conditions that enable genuine agency: schools to educate, courts to ensure fairness, healthcare to preserve life, and an economy that offers opportunities.

At its heart, positive liberty points to autonomy and self-mastery. To be free is to live deliberately, not at the mercy of ignorance, poverty, or manipulation. Universal education, equal access to justice, and protections against economic exploitation exemplify how societies create conditions where individuals can stand tall as autonomous beings. In this sense, liberty is not only a shield against interference but also a ladder that allows people to rise to their fullest potential.

C. Social Liberty: Freedom Through Community

A third dimension, often overlooked, is social liberty—the recognition that freedom is relational, not solitary. Hegel reminds us that individuality flourishes only in relation to others; we become fully human not in isolation but in a network of mutual recognition.

Freedom thus requires community. It is not the rugged independence of the solitary hero but the shared construction of spaces where each person’s dignity is acknowledged. Diversity plays a vital role here. Societies advance not by enforcing uniformity but by permitting “experiments in living”—the freedom to try new ideas, embrace different lifestyles, and challenge social norms.

History shows how such social liberty fuels progress: the civil rights movements in the United States, the dismantling of apartheid in South Africa, the spread of inclusive democratic participation across the globe. Each was not only an assertion of individual rights but also a collective demand for recognition, equality, and justice.

Social liberty reminds us that the use of freedom is never just personal—it is civic. To use freedom responsibly is to contribute to a world where others can also be free. Liberty, in this sense, is not diminished when shared; it is strengthened.

III. Responsibility: The Guardian of Freedom

Freedom without responsibility is not freedom at all—it is entropy masquerading as choice. Every liberty granted to us is shadowed by an obligation, and without this counterweight, liberty collapses into selfish indulgence, social fracture, or systemic breakdown. Responsibility is therefore not an external limitation imposed on freedom, but the very condition that gives it coherence, dignity, and endurance.

A. Ontological Bond

Philosophers have long insisted that liberty and responsibility are inseparable twins. Jean-Paul Sartre captured it with uncompromising clarity: “Man is condemned to be free.” For Sartre, freedom is never an escape from responsibility but its perpetual summons—every choice creates meaning not only for the self but also for humanity. To choose is to bear accountability.

When individuals accept this bond, liberty evolves beyond personal gratification into moral strength. Freedom, then, is not the licence to do whatever one wishes, but the conscious act of aligning one’s choices with the good of others, the community, and posterity. It is in this sense that responsibility functions as the guardian, ensuring that freedom does not consume itself.

B. Responsibility vs. Coercion

A critical distinction must be drawn between responsibility freely embraced and responsibility externally imposed. The former elevates freedom into maturity; the latter often smothers it under resentment. Voluntary restraint is morally superior to state coercion because it arises from inner discipline, not fear of punishment.

For instance, responsible journalism—fact-checking, respecting privacy, protecting the dignity of vulnerable groups—demonstrates freedom at its best. In contrast, blunt censorship laws, even if well-intentioned, corrode both liberty and trust. The paradox is that a society that does not cultivate responsibility will demand coercion, whereas one that fosters responsibility needs fewer external restrictions.

C. Misuse of Liberty: Neglecting Duties

If liberty is a gift, then neglect is its silent betrayal. Misuse often does not appear as direct abuse but as failure to uphold duties. A parent abandoning family obligations, a citizen evading taxes, or a voter refusing to participate in democracy—all corrode the social foundations that make liberty possible.

Equally, freedom demands positive duties. It is not enough to refrain from harming others; one must also contribute to collective well-being. Military service in times of peril, environmental stewardship in an age of climate collapse, or paying fair taxes in a fragile economy are not coercions but extensions of freedom into solidarity. They are the living proof that liberty thrives only when individuals accept sacrifices for the greater good.

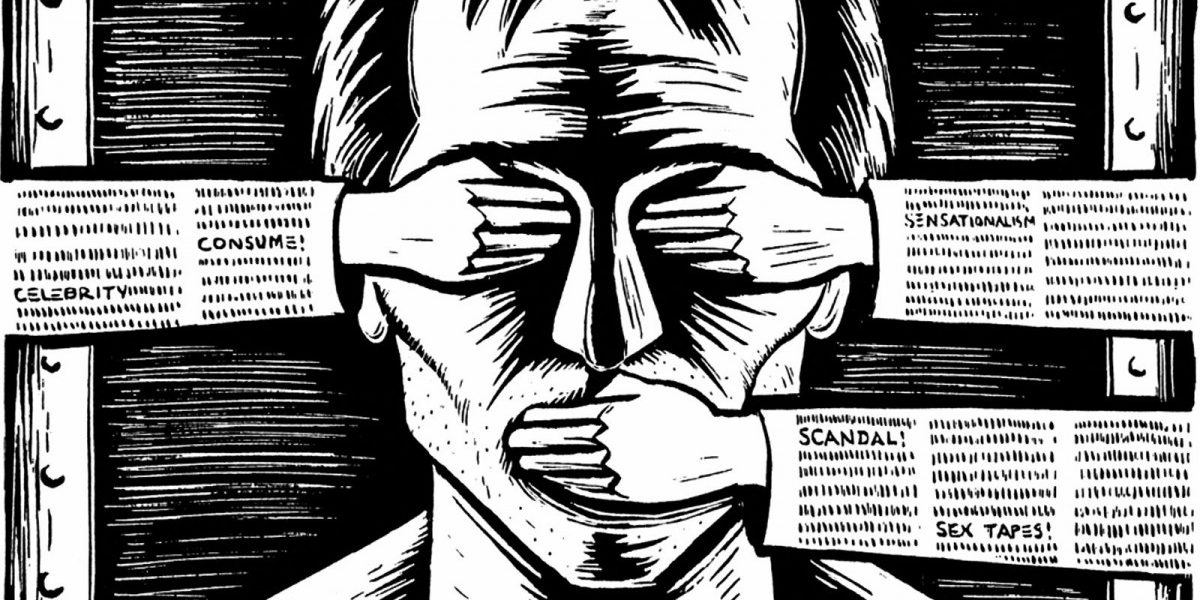

IV. Abuse of Freedom: When Liberty Becomes a Weapon

Freedom is not only vulnerable to neglect but also to weaponization. The very principle meant to liberate human potential can, if twisted, be turned against others and against itself. The abuse of freedom occurs when liberty ceases to be a sphere of self-realization and becomes a tool for domination, manipulation, or destruction. This is where the line between legitimate exercise of rights and their corrosion must be drawn with moral clarity.

A. Harm Principle as the Boundary

John Stuart Mill’s Harm Principle provides a sturdy compass: freedom ends where one person’s exercise of it inflicts real harm upon another. The legitimacy of restrictions rests here—violence, fraud, exploitation, and coercion are not expressions of freedom but its violation, for they strip others of their ability to act as free beings.

Equally important is recognizing false harms—mere offense, personal disapproval, or discomfort. To equate disagreement with oppression is to shrink the space for debate and experimentation that freedom requires. A society hypersensitive to “hurt sentiments” risks suffocating under the weight of its own fragility, mistaking inconvenience for injury.

B. Abuse Through Speech

Nowhere is the tension sharper than in speech. Words can liberate or enslave, enlighten or incite.

- Incitement & Threats: Speech becomes abuse when it ceases to argue and begins to command violence—whether in the form of mob incitement, terror threats, or calls for persecution. Here, words act as weapons, not ideas.

- Unjust Speech: Defamation, targeted harassment, and malicious propaganda corrode both individual dignity and public trust. Unlike genuine criticism, they aim not at truth but at silencing or destroying others.

- Abuse Clause (ECHR Article 17): Even in liberal frameworks, freedom of expression is not absolute. The European Convention on Human Rights explicitly denies protection to speech that seeks to abolish rights themselves—such as Holocaust denial or hate propaganda. A system that tolerates speech aimed at annihilating freedom undermines its own foundation.

Thus, free speech must be defended robustly, but not unconditionally. The challenge is to separate the uncomfortable from the unacceptable, critique from cruelty, dissent from destruction.

C. Abdication of Freedom

Perhaps the most insidious abuse is not aggression against others but the surrender of one’s own liberty. The voluntary slavery paradox shows that freedom cannot legitimately be used to abolish itself; one cannot sell or enslave their own autonomy, for that would destroy the very capacity to choose.

In modern societies, this abdication often takes subtler forms:

- Addiction to technology, where attention and agency are outsourced to algorithms.

- Corporate manipulation, where consumer choice is engineered by surveillance capitalism.

- Radical relativism, where the idea that “truth is whatever I say it is” erodes any shared moral horizon, leaving only power as arbiter.

The consequence of such abdication is stark: the erosion of universal human rights and a return to the oldest, harshest law of all—rule by force. When individuals relinquish freedom in exchange for convenience or illusion, society risks slipping into quiet servitude under new masters.

V. Institutional Safeguards and Limits

Freedom, to endure, requires not only individual responsibility but also carefully designed institutional frameworks. Laws, courts, and regulations are meant to serve as fences—restraining excess without caging liberty. Yet the paradox remains: too much protection curdles into paternalism, while too little collapses into anarchy or exploitation. The art of governance lies in finding the equilibrium where institutions act as guardians, not masters.

A. Rejecting Paternalism and Moralism

John Stuart Mill’s stern warning remains as urgent today as it was in the 19th century: the state should not override the informed choices of adults “for their own good.” To treat citizens as children incapable of self-governance is to insult their dignity and hollow out freedom.

That said, Mill conceded the legitimacy of soft paternalism—intervention when choices are made in ignorance or under deception. Cigarette health warnings, mandatory disclosures of financial risks, or truth-in-labeling laws do not crush liberty; they enhance it by ensuring choices are informed rather than manipulated.

By contrast, hard paternalism—outright bans on risky lifestyles such as consuming alcohol, extreme sports, or unconventional diets—betrays freedom in the name of safety. A society that insists on protecting people from themselves ends up producing dependency, not autonomy. The line between care and control must be vigilantly patrolled.

B. Freedom in the Digital Age

If the 20th century was a battlefield for political liberty, the 21st is the frontline of digital freedom. Data privacy and online speech are now the crucibles where liberty is tested.

- Data privacy: Citizens cannot be free if every click, purchase, and conversation is harvested for profit or surveillance. The right to control one’s digital identity has become as fundamental as the right to one’s body.

- Accountability of tech giants: Companies that build algorithms shaping thought, behavior, and elections wield quasi-sovereign power. Transparency in content moderation, algorithmic fairness, and respect for users’ rights are no longer optional—they are democratic imperatives.

- The state’s role: Governments face the razor’s edge. On one side lies dereliction, allowing corporations to morph into digital oligarchies; on the other lies digital authoritarianism, where “regulation” mutates into censorship and surveillance. The challenge is minimal but effective oversight—rules that restrain abuse without suffocating innovation or liberty.

C. Legal & Constitutional Mechanisms

Constitutions and legal frameworks provide the formal scaffolding of liberty. Yet their legitimacy depends on striking balance between rights and responsibilities.

- Freedom of expression tied to duties: For instance, Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights guarantees free expression but simultaneously recognizes responsibilities and limits, ensuring rights are not exercised in destructive ways.

- Criteria for restriction: Restrictions on liberty must pass a triple test—legality (clear basis in law), legitimate aim (protection of rights, security, or order), and proportionality (the narrowest possible limitation to achieve the aim).

- The test of democracy: Ultimately, a society must ask: do restrictions preserve the conditions of freedom, or do they smother them? The line between protection and oppression is thin, and only vigilant democratic culture can prevent drift toward authoritarianism.

Institutions cannot guarantee liberty by themselves—they can only frame it. Their effectiveness depends on citizens who are informed, vigilant, and unwilling to trade freedom for comfort.

VI. Conclusion: The Perpetual Choice of Liberty

Freedom is never a finished achievement; it is a choice renewed in every generation, every institution, and every individual decision. The paradox remains constant: liberty is humanity’s highest crown, yet without responsibility, it corrodes into its own enemy.

A. Balance Recap

- Use: At its best, freedom empowers autonomy, preserves dignity, and fuels human progress. It is the soil in which creativity, justice, and solidarity grow.

- Misuse: When liberty is treated as licence without duty, it erodes trust, weakens communities, and drains meaning from rights. Neglect is the slow poison of freedom.

- Abuse: When liberty is weaponized against others—through violence, exploitation, or manipulation—it becomes self-destructive, undermining the very rights it claims to defend.

B. Call for Responsible Liberty

Freedom is not a passive inheritance, secured forever by the struggles of the past. It is a living responsibility, demanding vigilance, sacrifice, and moral imagination. A society’s strength lies not merely in its laws, but in the responsibility of its citizens—the willingness to restrain impulses, honor obligations, and defend the vulnerable.

Our generation’s challenge is stark: to conquer freedom anew, not through revolution, but through responsibility. To wield liberty not as a weapon of self-interest but as a tool of collective flourishing. Every choice we make—what we consume, how we speak, how we care for one another—is a vote for either the preservation or the erosion of freedom.

👉 Participate and Donate to MEDA Foundation

Join us in building ecosystems where every individual—including autistic persons and marginalized groups—can exercise liberty responsibly, with dignity and opportunity. Together, let us ensure freedom is never misused or abused.

Book References

- John Stuart Mill, On Liberty

- Isaiah Berlin, Two Concepts of Liberty

- Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness

- Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition

- Amartya Sen, Development as Freedom

- Philip Pettit, Republicanism: A Theory of Freedom and Government