Nature has its own ways of signaling which foods are most nutritious, often defying modern assumptions. Contrary to the belief that healthy food lacks flavor, nature suggests that the tastiest, freshest, and most vibrant foods are often the most nutritious. Brightly colored fruits and vegetables, especially those in rich blues, purples, and reds, are packed with antioxidants and essential nutrients. Foods that are harder to access, whether protected by tough shells or grown in challenging environments, often contain concentrated nutrition. Additionally, smaller fruits tend to be more nutrient-dense, and those harvested at their peak freshness require no processing to be both delicious and nourishing, reinforcing nature’s inherent wisdom.

Introduction

Theories of Nutrition: Back in the days when access to advanced scientific testing and research was limited, people relied on observation and wisdom passed down through generations to understand what foods were nutritious. Wise individuals, often with a deep connection to the land and nature, began to notice patterns in the natural world that hinted at the nutritional value of different foods. They observed the effects that various plants, fruits, and vegetables had on human health and developed theories based on these insights.

These theories, while not backed by modern scientific methods at the time, were formed through centuries of collective knowledge and experience. Many people today continue to live by these observations, reporting improved well-being and better health outcomes as a result of embracing nature’s bounty. By learning from the natural world, these early observers understood how to nourish the body in a way that aligned with the rhythms of the earth and human biology.

These theories, while not backed by modern scientific methods at the time, were formed through centuries of collective knowledge and experience. Many people today continue to live by these observations, reporting improved well-being and better health outcomes as a result of embracing nature’s bounty. By learning from the natural world, these early observers understood how to nourish the body in a way that aligned with the rhythms of the earth and human biology.

The following article explores some of these enduring theories that have been passed down through generations. While these ideas offer fascinating insights into natural nutrition, it’s important to recognize that they remain unproven by contemporary science.

Disclaimer: The following theories are based on collective wisdom and are intended for informational purposes. They should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or treatment. Always consult with a healthcare provider before making any significant changes to your diet or lifestyle based on these ideas.

Flavor as a Sign of Nutrient Density

Theory: The tastier and more flavorful a food, the more nutritious it is.

Explanation: Natural foods with complex and layered flavors often signal high nutrient density, containing vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients essential for health. Our taste receptors identify various sensations—sweet, sour, salty, bitter, astringent, pungent, and umami—that provide an understanding of a food’s nutritional content. Nature presents these flavors in unique combinations that stimulate both taste and smell, offering sensory experiences that are hard to document. For instance, both lemon and tamarind are sour, yet their taste profiles are vastly different, reflecting their distinct nutrient compositions.

Modern food processing, however, tends to homogenize flavors, making different food products taste increasingly similar. This has dulled our sensitivity to the diverse and complex flavors found in fresh, natural foods, which often serve as indicators of nutrient-rich options.

Psychological Impact of Nutrient-Dense vs. Processed Foods

The psychological effects of eating flavorful, nutrient-dense foods differ greatly from those of consuming processed, flavor-uniform foods. When we eat fresh, flavorful foods, our brains receive signals of satisfaction and nourishment. These natural flavors, which are dynamic and layered, engage multiple senses and provide a more fulfilling eating experience. Psychologically, eating such foods can make us feel more connected to our bodies, increase mindfulness during meals, and foster a sense of well-being. A vibrant fruit salad, rich with the colors and flavors of ripe fruits, can leave you feeling refreshed, revitalized, and energized.

On the other hand, processed foods are often designed to deliver a quick, uniform flavor hit, usually leaning heavily on sweetness, saltiness, or fat content to stimulate our taste buds. While they may taste pleasant, they do not engage the senses in a complex way, and over time, can reduce our appreciation for the subtle flavors found in natural foods. This can lead to overeating, as processed foods are engineered to trigger cravings without delivering the satiety and nutrition our bodies require. For example, consuming sugary snacks may give an immediate dopamine rush, but it often leaves people feeling unsatisfied and prone to eating more without truly nourishing the body.

Real-Life Instances: Natural vs. Processed Foods

In the real world, the difference between eating natural, nutrient-dense food and processed alternatives is stark. Imagine biting into a ripe, juicy mango. Its sweetness is layered with hints of tanginess, and the aroma is fragrant and rich. This experience is not only pleasurable but also nourishing—mangoes are high in vitamins A and C, fiber, and antioxidants. Eating this mango leaves you satisfied both nutritionally and emotionally, as the vibrant flavors signal that your body is receiving beneficial nutrients.

Contrast this with eating a bag of artificially flavored, processed fruit snacks. These snacks might taste sweet, but the flavors are uniform, and there’s little complexity beyond the sugary coating. Despite the initial enjoyment, you may soon find yourself reaching for more, as the satisfaction is fleeting. The processed version lacks the vitamins, fiber, and other nutrients found in the real fruit, leaving your body still craving real nourishment.

Actionable Steps to Implement This Knowledge

Reintroduce Variety into Your Diet: One way to bring back the enjoyment of nutrient-dense foods is to diversify your diet with fresh, seasonal produce. Try incorporating fruits and vegetables of different colors and flavors—like bitter greens, sweet berries, or sour citrus—into your daily meals. Pay attention to the natural flavors, and practice mindful eating to appreciate the subtle differences in taste.

Minimize Processed Foods: Reducing your consumption of processed and packaged foods can help retrain your palate to enjoy the natural flavors of whole foods. Start by replacing processed snacks with fresh alternatives, such as swapping chips for a mix of raw nuts or opting for a piece of fruit instead of a candy bar. Over time, your taste buds will become more attuned to the richness of natural flavors.

Cook with Fresh Ingredients: Whenever possible, cook your meals using fresh, unprocessed ingredients. Cooking from scratch allows you to experiment with natural flavors, herbs, and spices, which will enhance the taste and nutritional value of your meals. For example, instead of using bottled sauces or pre-made seasonings, try seasoning your dishes with fresh garlic, ginger, herbs, or citrus to bring out complex flavor profiles while preserving nutrients.

By making these small changes in your daily routine, you can reconnect with the natural complexity and richness of whole foods, leading to both improved health and a more satisfying eating experience. This approach not only nourishes the body but also enhances your overall relationship with food, fostering mindful and balanced eating habits.

Color as a Nutritional Indicator

Theory: Darker, richer, and more vibrant colors signal higher nutritional value.

Explanation: Foods with deep, vibrant colors often contain elevated levels of antioxidants, vitamins, and essential nutrients. The pigments responsible for these colors are bioactive compounds, such as anthocyanins, carotenoids, and chlorophyll, which offer significant health benefits. For example, anthocyanins, which give blueberries and blackberries their deep blue and purple hues, have been shown to reduce inflammation and improve brain health. Similarly, beta-carotene, the pigment in orange foods like carrots and sweet potatoes, is a powerful antioxidant that supports vision and immune function.

The correlation between color frequency and nutrient density can also be understood through the visible light spectrum. Darker foods like deep blue, violet, and indigo fruits have pigments that absorb higher frequencies of light, which are often linked to antioxidant activity. Studies confirm that foods like dark leafy greens, richly colored berries, and vibrant root vegetables are packed with micronutrients. For instance, the darker the green in vegetables like spinach and kale, the more chlorophyll they contain, which has detoxifying properties.

Psychological Impact of Color Preferences in Food

Throughout history, the association of lighter colors with purity and superiority has led to the preference for pale or refined foods in many cultures, especially those impacted by colonization. In regions colonized by lighter-skinned people, there has been an ingrained notion that everything pale is better. This preference can be seen in the widespread use of refined white sugar over brown sugar, white bread over whole grain, and polished rice over unrefined varieties. These cultural biases may cause people to overlook the nutritional value of darker, richer foods, despite their superior health benefits.

On the other hand, embracing the vibrant, dark, and rich colors of nature’s bounty can have a positive psychological impact. When we consume deeply colored foods, we often feel more connected to the earth and its natural resources. These foods visually signal abundance, vibrancy, and health. Shifting towards darker, colorful foods can also foster a more inclusive mindset, allowing individuals to embrace the diversity of nature and celebrate all forms of nourishment.

Real-Life Instances: Light vs. Dark Foods

Consider the difference between refined and unrefined grains. White rice, stripped of its outer bran, germ, and husk, is pale and visually “cleaner” but lacks much of the fiber, vitamins, and minerals found in its unpolished, darker counterpart. While white rice may be more popular, it’s the brown or black rice varieties that offer the most nutritional benefits.

Another example is the choice between dark leafy greens and iceberg lettuce. Many people gravitate toward the lighter, crisp texture of iceberg, but it pales (literally and nutritionally) in comparison to dark greens like spinach, kale, or Swiss chard. Dark greens are loaded with fiber, iron, calcium, and antioxidants, while iceberg lettuce is mostly water with few nutrients.

Culturally, lighter foods like white bread and refined sugar have long been associated with higher socioeconomic status. In many societies, darker or less refined foods were often seen as inferior. However, science shows us that the darker, unrefined versions are nutrient-dense and contribute more significantly to overall health.

Actionable Steps to Implement This Knowledge

Add Color to Every Meal: Make it a habit to include at least one dark, colorful food in every meal. Whether it’s a handful of blueberries with breakfast, dark leafy greens in your salad, or a serving of roasted beets for dinner, vibrant colors signal nutrient density. Challenge yourself to “eat the rainbow” and prioritize deep blues, reds, purples, and greens in your diet.

Choose Whole Foods Over Refined Options: Whenever possible, opt for unrefined, darker alternatives to common foods. Replace white rice with brown or black rice, and swap out white bread for whole grain varieties. By choosing less processed, more colorful options, you are likely to increase your intake of essential nutrients without compromising on taste.

Embrace Cultural Food Diversity: Be mindful of cultural biases that may have led to the preference for lighter foods. Explore and embrace traditional foods from different regions that are rich in color and nutrition, such as black beans, red quinoa, or dark leafy greens like collard greens or amaranth leaves. Celebrate the diversity of nature’s bounty and move away from the outdated notion that lighter is always better.

By incorporating these simple steps into your daily life, you can benefit from the full spectrum of nutrients that nature offers through its richly colored, vibrant foods. Not only will this improve your health, but it will also foster a more diverse and inclusive approach to food, acknowledging the power and beauty of nature’s most nutrient-dense offerings.

Hard-to-Access Foods and Nutritional Value

Theory: The more difficult it is to access a food, the more nutritious it is.

Explanation: In nature, foods that are harder to access often contain concentrated nutrients that require effort to obtain. These foods, such as nuts with tough shells or fruits that grow high in trees and are available only during short seasons, tend to be more nutrient-dense. Their hardness to access is nature’s way of ensuring a balance between consumption and effort, making them rare treats rather than staples. For example, walnuts and almonds, hidden inside tough shells, are packed with healthy fats, proteins, and vitamins. Similarly, fruits like coconuts or lychees, which have hard exteriors or brief growing periods, are loaded with nutrients.

This theory suggests that the difficulty in obtaining these foods serves two purposes. First, the physical effort or patience required to access such foods creates a psychological satisfaction, enhancing the appreciation of their nutrition. Second, because they are harder to access, they naturally limit excessive consumption. Urban conveniences, like pre-shelled nuts or year-round availability of exotic fruits, have disrupted this balance. The easy accessibility of nutrient-dense foods often leads to overconsumption, which can cause health problems such as obesity or nutrient imbalance.

Psychological Impact of Easy vs. Hard-to-Access Foods

The psychological effect of effortful eating is significant. When foods are easy to access and available in abundance, they are often consumed mindlessly. This leads to overeating without a real appreciation for their value. In contrast, when a food requires effort—whether it’s cracking a walnut shell, climbing a tree to pick a mango, or waiting for a fruit’s short season—it creates a sense of achievement and satisfaction. This effort can serve as a natural regulator, making people more mindful of their consumption and, ultimately, enhancing their enjoyment and appreciation of the food.

In urban environments, where technology and convenience have removed many of these natural barriers, people tend to overconsume high-calorie, nutrient-dense foods. For instance, nuts are highly nutritious, but when pre-shelled and sold in bulk, they can be eaten in large quantities, leading to excess caloric intake. Conversely, the act of cracking and de-shelling nuts forces people to eat them more slowly, giving the body time to signal satiety, thereby preventing overconsumption.

Real-Life Instances: Effort vs. Ease in Food Consumption

A striking example of this can be found in the consumption of coconuts. In regions where coconuts grow naturally, locals often climb trees to harvest them, then crack open the hard shell to drink the water and eat the flesh. This effort naturally limits how many coconuts one can consume. On the other hand, in modern grocery stores, coconut water is available in convenient, pre-packaged bottles. This ease of access may lead to overconsumption, which diminishes the special value the food traditionally held and can even lead to excessive sugar intake.

Similarly, nuts are another prime example. In traditional cultures, cracking open hard walnut shells was a laborious task, and people consumed them in moderation. Today, shelled walnuts are readily available, and it’s easy to consume them in large amounts without thinking twice. This easy access can lead to overeating, which undermines the balance nature intended.

Actionable Steps to Implement This Knowledge

Seek Whole, Unprocessed Forms: Whenever possible, choose foods in their most natural form. Buy nuts in their shells, and opt for whole fruits with skins rather than pre-packaged, processed options. This extra effort will naturally slow down your consumption, giving you time to appreciate the food and regulate your intake more mindfully. The act of working for your food can help restore balance in your diet and prevent mindless overeating.

Embrace Seasonal Eating: Make a conscious effort to consume fruits and vegetables that are in season. This not only helps you align with nature’s cycles but also allows you to appreciate the fleeting availability of certain nutrient-dense foods. For example, enjoy mangoes during their short summer season, rather than opting for out-of-season imports. The scarcity will enhance your appreciation and prevent overconsumption.

Practice Mindful Eating: Take time to acknowledge the effort that went into obtaining or preparing your food. Whether it’s cracking open a walnut, peeling a pomegranate, or slicing open a coconut, be present in the process. This mindfulness helps connect you to the value of the food and reduces the tendency to overeat. Try incorporating rituals, like taking a moment of gratitude before a meal, to further enhance the psychological benefit of effortful eating.

By reintroducing the element of effort into your eating habits, you can not only enjoy foods in moderation but also appreciate their inherent nutritional value. This return to nature’s balance can foster healthier relationships with food and prevent the overconsumption of nutrient-dense but calorie-heavy items.

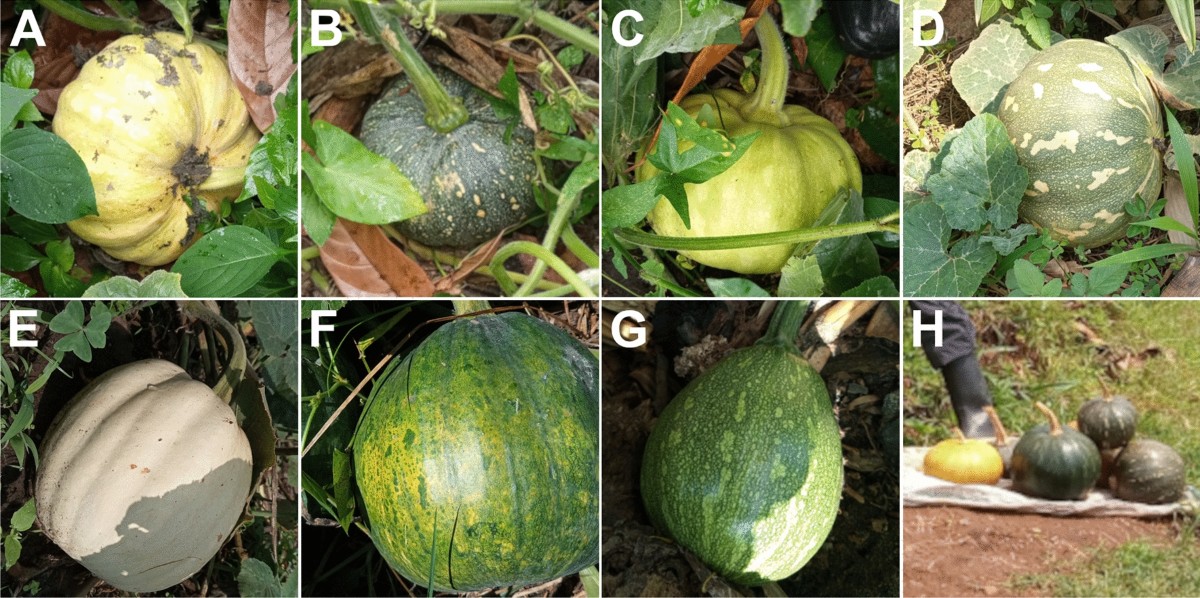

Smaller, Weaker Plants Yield More Nutritious Fruits

Theory: Foods growing on smaller, weaker plants are more nutrient-dense.

Explanation: Plants that are smaller and weaker tend to concentrate their limited resources into producing highly nutritious fruits. Since these plants do not have the vast reserves of energy that larger, more robust plants do, they focus their efforts on creating nutrient-rich fruits to ensure survival and reproduction. The idea is that the plant, in its fight for survival, channels more nutrition into its seeds and fruits to continue its lineage, which leads to denser, more nourishing produce.

Wild berries are an excellent example of this phenomenon. These small, delicate plants produce fruits packed with antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals to protect and sustain the next generation. Similarly, fruits from less-cultivated plants, like wild strawberries or heirloom tomatoes, often have higher nutrient profiles compared to their mass-produced counterparts. The flavor of these fruits is also more complex and vibrant, indicating a higher concentration of nutrients and natural compounds.

Psychological Impact of Smaller vs. Larger Plants

The psychological aspect of this theory also plays a role in human perception. Larger, cultivated plants—often associated with industrial farming—produce fruits that are bigger, easier to grow, and more visually appealing. However, these fruits are often bred for appearance, size, and yield rather than nutrition. As a result, consumers may equate bigger fruits with better quality, when in fact the smaller, seemingly less impressive fruits from weaker plants can be far more beneficial.

On the flip side, wild or heirloom varieties of fruits, which often appear less uniform or are smaller in size, might be overlooked. However, these fruits, having grown in less controlled environments, tend to have more intense flavors and a greater nutrient density, making them healthier options.

Real-Life Instances: Smaller Plants, Bigger Nutrients

A real-life example can be seen in the comparison between wild blueberries and cultivated blueberries. Wild blueberries, which grow on smaller, less robust bushes, are typically smaller in size but are packed with significantly more antioxidants than their larger, cultivated counterparts. The wild berries have a much more intense flavor, further signaling their concentrated nutrients.

Another instance is found in heirloom varieties of fruits and vegetables, which are often smaller and less uniform than the modern, cultivated versions seen in supermarkets. Heirloom tomatoes, for example, are smaller and more prone to blemishes but are celebrated for their richer taste and higher nutrient content.

Actionable Steps to Implement This Knowledge

Opt for Wild or Heirloom Varieties: When available, choose wild or heirloom varieties of fruits and vegetables. These foods often grow on smaller plants that have not been heavily cultivated, meaning they are likely to contain more concentrated nutrients and richer flavors. Look for local farmers’ markets or specialty stores that carry these varieties.

Focus on Nutrient Density Over Size: Avoid selecting fruits or vegetables solely based on their size or appearance. Larger fruits are not always more nutritious. Instead, prioritize smaller, more flavorful options, as these often come from plants that have focused their energy on producing nutrient-rich produce.

Grow Your Own: Consider growing smaller plants like wild berries or heirloom tomatoes in your garden. Smaller, weaker plants often thrive in less fertile soils and require fewer interventions, making them a great addition to a home garden. This allows you to enjoy fresh, nutrient-dense produce straight from the source.

By embracing smaller plants and their nutrient-packed fruits, you can enhance your diet with foods that are naturally more nourishing, flavorful, and beneficial for long-term health.

Slower Growth Equals More Nutrients

Theory: Foods that take longer to develop are more nutritious.

Explanation: Slow-growing plants and fruits have more time to absorb nutrients from the soil, resulting in more nutrient-dense produce. The gradual growth allows the plant to accumulate a richer array of vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals. These compounds are not only essential for the plant’s own survival and reproduction but also contribute to the nutritional quality and flavor complexity of the food we consume. The patience required for these foods to mature translates into a higher nutritional payoff.

In contrast, faster-growing crops are often cultivated for speed and size rather than nutritional content. They may not have the time to fully absorb nutrients from the soil, resulting in fruits and vegetables that are larger but less nutritionally potent. For example, modern agricultural practices often prioritize quick yields and large quantities, sometimes at the cost of nutrient density.

Psychological Impact of Quick vs. Slow Growth Foods

In today’s fast-paced society, there is a tendency to favor convenience and instant gratification. Fast-growing, quickly available produce fits into this mindset, leading many to equate speed and size with quality. However, the deeper, more nourishing foods that take time to grow may be overlooked due to their limited availability or higher cost.

On the psychological front, consuming foods that have taken time to grow can foster a greater sense of appreciation and mindfulness. These foods, with their more complex flavors and nutrient profiles, offer a more satisfying and wholesome experience. This connection between patience, growth, and nourishment can remind us that good health and well-being also require time and care.

Real-Life Instances: Slow-Growing Plants and Nutrient Density

A prime example of this theory is the avocado tree. Avocado trees can take several years to bear fruit, but the payoff is significant. Avocados are packed with healthy fats, vitamins, and minerals, and their rich, creamy texture is a result of the slow maturation process. Another example is chestnut trees, which also take years to produce their first crop but yield highly nutritious nuts rich in fiber, vitamins, and antioxidants.

Heirloom varieties of fruits and vegetables are another excellent example. These slow-growing, non-hybrid plants have more time to develop robust nutrient profiles and unique flavors. Heirloom tomatoes, for instance, are celebrated for their intense taste and higher nutrient content compared to commercially grown, fast-yielding tomatoes.

Actionable Steps to Implement This Knowledge

Prioritize Heirloom and Slow-Growing Varieties: Seek out heirloom varieties of fruits and vegetables at farmers’ markets or specialty grocery stores. These slower-growing varieties are more likely to have higher nutrient concentrations and richer, more complex flavors compared to mass-produced, faster-growing counterparts.

Be Patient with Seasonal Produce: Opt for foods that take longer to grow and are available only during certain seasons, such as chestnuts, avocados, or other tree fruits. Eating seasonally not only supports slow-growing produce but also ensures that you’re consuming fruits and vegetables at their peak nutritional value.

Grow Your Own Slow-Growing Plants: If you have the space, consider growing slow-growing plants like avocado or chestnut trees, or cultivate heirloom vegetables in your garden. While these plants may take more time to bear fruit, the nutritional benefits of your patience will be worthwhile.

Embracing slower-growing foods in your diet means choosing nutrient-dense, flavorful produce that supports long-term health. By giving these foods the time they need to mature, you also invest in your own well-being through thoughtful and nutrient-rich choices.

Food Shape and Human Health

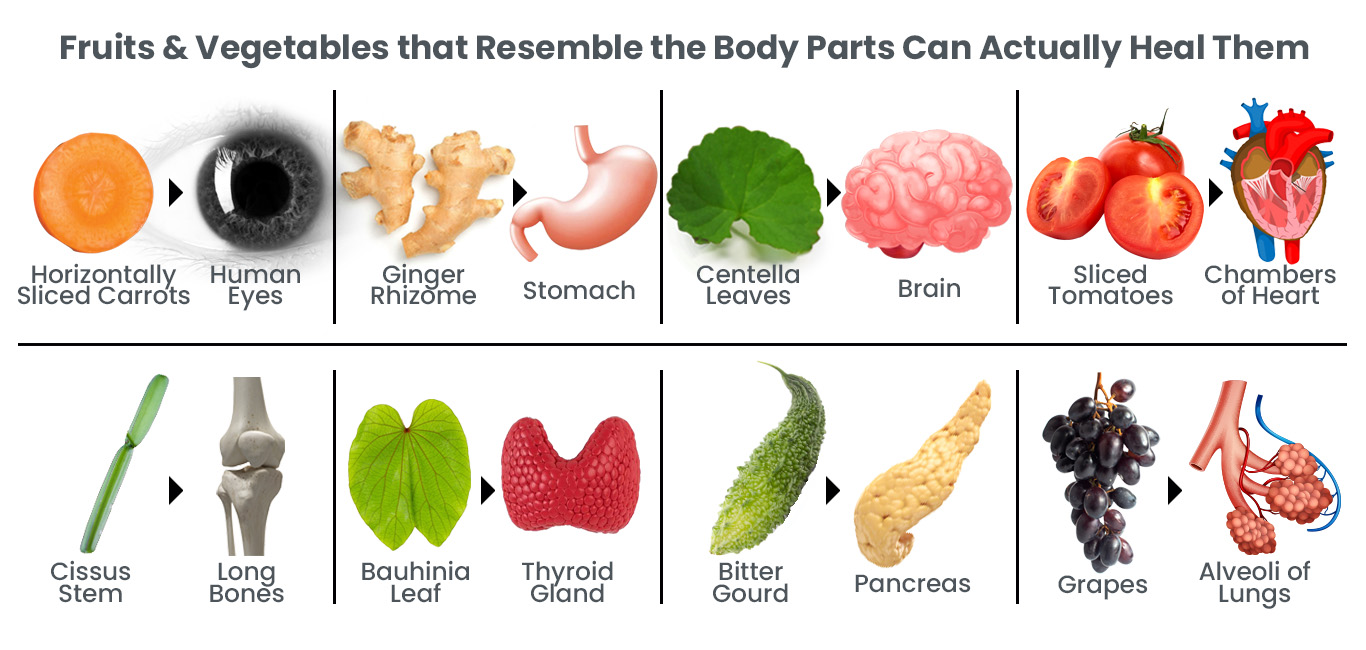

Theory: Foods that resemble parts of the human body may benefit those organs.

Explanation: This theory suggests that the shape of certain foods can indicate the organ or body part they support. Known as the “Doctrine of Signatures,” this belief stems from ancient times, where people observed that foods that resembled human organs could be beneficial for those particular parts of the body. While modern science has not fully validated this theory, it is fascinating how often the nutrient profile of these foods aligns with the health benefits they offer to the organ they resemble.

Examples: Walnuts, with their brain-like shape, are rich in omega-3 fatty acids, which are known to support brain health. Kidney beans resemble kidneys and are packed with fiber and nutrients that promote kidney function. Carrots, when sliced, resemble the iris of an eye, and they contain beta-carotene, which supports eye health and vision. Other examples include ginger resembling a stomach and being effective in aiding digestion, and tomatoes, with their four chambers like the heart, being rich in lycopene, a compound that supports heart health.

Psychological Impact of Food Resemblance

On a psychological level, the visual resemblance between foods and body parts creates a unique connection. This connection encourages people to be more mindful of their food choices, fostering a sense of intentional eating and well-being. The idea that nature has provided these visual clues can lead to a deeper appreciation of food as medicine and encourage more thoughtful consumption. On the other hand, modern diets have distanced people from natural, unprocessed foods, potentially weakening this inherent connection between appearance and health benefits.

Real-Life Instances of Food Resemblance and Health

A common example of this theory in action is the use of walnuts in promoting brain health. The brain-shaped nut is rich in compounds that enhance cognitive function. Another example is kidney beans, often recommended for people with kidney issues due to their fiber content, which aids in maintaining kidney health. Carrots, with their visual similarity to the eye, are loaded with beta-carotene, a precursor to vitamin A, which is crucial for vision and eye health.

Actionable Steps to Implement This Knowledge

Pay Attention to Natural Visual Cues: Next time you’re shopping for produce, consider how the shape of certain foods might reflect their health benefits. Incorporate more foods that resemble human organs into your diet for targeted support.

Research the Nutritional Benefits: While the visual resemblance of foods to organs is intriguing, it’s important to verify the actual nutrients they contain. Research foods that are known for their health benefits and incorporate them into your diet based on their nutritional value.

Mindful Eating and Gratitude: The idea that food’s shape can signal its health benefits encourages mindfulness. When preparing meals, take time to appreciate the form and function of your food, and reflect on how nature may provide subtle clues to guide your health choices.

Embracing the concept of food shape as a guide to nutrition can add a thoughtful, mindful element to your eating habits. While not scientifically definitive, it’s an interesting and holistic approach to making food choices that align with both tradition and health goals.

Skins Protect the Food and the Body

Theory: The protective outer layer of food offers nutritional and health benefits.

Explanation: The skin or outer layer of fruits and vegetables often contains a concentrated source of fiber, antioxidants, and other essential nutrients that serve to protect the food from environmental threats. In the same way, these compounds can offer protective health benefits to the human body. For example, fiber aids in digestion and helps regulate blood sugar, while antioxidants reduce oxidative stress and inflammation. In many cases, removing the skin can strip away a significant portion of the food’s nutritional value.

Examples: Apples, when eaten with the skin, provide a good source of fiber and vitamin C. Potatoes, particularly sweet potatoes, have fiber-rich skins packed with nutrients like potassium and iron. Cucumbers, when consumed with their skin, provide additional fiber and vitamin K. Other examples include carrots and eggplants, whose skins are rich in phytonutrients, contributing to overall health.

Psychological Impact of Skin Consumption

Many people grow up with the idea that food skins should be peeled off, partly due to concerns about texture, taste, or even safety (like pesticides). This has led to a general dismissal of the nutritional benefits skins offer. However, modern understanding highlights how significant these skins are for health. On the flip side, some individuals still hesitate to eat skins due to lingering misconceptions, especially in cultures where food refinement (such as peeling) is equated with higher quality or sophistication. Shifting this perspective can lead to healthier choices and greater appreciation of whole foods.

Real-Life Instances of Skins as Protectors

Farmers and nutritionists alike emphasize the value of eating fruits and vegetables with their skins. Apples are often recommended as a whole food precisely because the skin is rich in quercetin, an antioxidant linked to heart health and anti-inflammatory effects. Potatoes, which are often peeled before cooking, lose much of their nutrient content when stripped of their skin. Additionally, individuals in cultures where vegetables like cucumbers or carrots are consumed raw and unpeeled enjoy a higher intake of vitamins and minerals compared to those who discard the skins.

Actionable Steps to Implement This Knowledge

Choose Organic or Wash Thoroughly: If pesticide exposure is a concern, opt for organic produce or thoroughly wash conventional fruits and vegetables to remove residues before consuming their skins.

Incorporate Whole Foods: Start including more fruits and vegetables in your diet with the skins on. Simple changes like eating apples and cucumbers without peeling can significantly boost fiber and nutrient intake.

Explore Cooking Techniques: Roasting vegetables like carrots or potatoes with their skins on not only preserves their nutritional value but also enhances flavor and texture. Try experimenting with different cooking methods that highlight the benefits of the skins.

By embracing the outer layers of food, you can maximize the nutritional potential of your diet. Rather than discarding this protective and nutrient-rich part of your produce, see it as an essential component of your meals.

Heavy Foods and Digestion

Theory: Nutrient-dense foods are heavier to digest, requiring balance with lighter foods.

Explanation: Foods that are rich in essential nutrients, such as nuts, seeds, legumes, and heavy grains, tend to be heavier on the digestive system. These dense foods are ideal for those who need extra nourishment, like the elderly, children, or individuals recovering from illness or injury, as they aid in rebuilding and healing. However, for healthy individuals, regular consumption of heavy, nutrient-rich foods may not be necessary and can overwhelm the digestive system. Overeating such foods can lead to indigestion, sluggishness, or nutrient imbalances. It’s important to balance these heavier foods with lighter, easier-to-digest options, like fruits, leafy greens, and vegetables, to maintain optimal health and digestion.

Examples: Nuts and seeds, while packed with healthy fats, proteins, and minerals, can be tough to digest if eaten in excess. Legumes, such as lentils and chickpeas, are rich in fiber and protein but can cause bloating or discomfort if not balanced with lighter, more water-based foods like salads. Similarly, heavy grains like oats and barley are highly nutritious but may weigh down the digestive system if eaten frequently without lighter counterparts.

Psychological Impact of Balancing Heavy and Light Foods

In many cultures, heavy foods are associated with celebrations or times of recovery, while lighter foods are linked to everyday sustenance. This contrast creates a psychological expectation that rich, heavy foods are indulgent or special, often leading people to overconsume them during holidays or stress periods. On the flip side, there’s a common misconception that heavier foods are always “healthier,” leading some to overload their diets with nutrient-dense foods, which may not be suitable for daily consumption. Balancing the psychological craving for these richer foods with an understanding of their digestive effects can help create healthier eating habits.

Real-Life Instances of Digestive Imbalance

In urban environments, where access to processed and calorie-dense foods is convenient, many people suffer from digestive issues like bloating, indigestion, and even nutrient deficiencies due to overconsumption of heavy foods. For example, regular consumption of energy-dense snacks like nuts and seeds without balancing them with fresh fruits or vegetables can lead to constipation or sluggish digestion. Conversely, rural communities that balance heavy staples like grains with light, seasonal produce often report fewer digestive problems.

Actionable Steps to Implement This Knowledge

Monitor Your Digestive Response: After consuming heavy foods, pay attention to how your body feels. If you notice discomfort, consider reducing the quantity or pairing these foods with lighter options.

Prioritize Balance: For every serving of heavy, nutrient-dense food, pair it with a lighter, hydrating component like leafy greens, cucumbers, or citrus fruits to aid digestion and absorption.

Use Heavier Foods Strategically: Incorporate heavier, more nutrient-rich foods into your diet during times when your body needs extra support, such as during illness recovery, pregnancy, or periods of intense physical activity. Keep your daily meals lighter when you’re in a regular health state.

Achieving balance in your diet between heavy, nutrient-dense foods and lighter options can improve digestion, prevent overconsumption, and enhance overall well-being.

Nature’s Uninfluenced Growth Yields Better Nutrition

Theory: Foods grown without human intervention may be more nutritious than those cultivated for profit.

Explanation: Wild foods that grow in natural environments without human interference often develop their nutrient profiles more organically. Unlike commercially grown produce, which is often influenced by farming practices geared towards yield, appearance, or profit, wild foods rely solely on their natural surroundings to thrive. These naturally grown plants adapt to local soil, climate, and ecological conditions, allowing them to absorb more diverse and often concentrated nutrients. Because they are not artificially fertilized or genetically modified, they retain their authentic nutritional content, making them more nutrient-dense than cultivated counterparts. Nature’s uninfluenced growth fosters a richer, more complex nutritional composition.

Examples: Wild berries like blackberries or elderberries, which are foraged from untamed areas, are often more potent in vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants compared to farmed varieties. Nuts like hazelnuts or walnuts that grow in the wild and fruits from untended trees, such as those found in forests, often exhibit more robust nutrient profiles due to their natural growing conditions.

Psychological Impact of Natural vs. Cultivated Foods

There is a growing awareness around the benefits of wild or organic foods, as people recognize the limitations of industrial agriculture. This realization creates a psychological preference for more “natural” foods, leading to increased demand for organic and foraged options. On the other hand, cultivated foods are often associated with convenience, affordability, and uniformity, which may make them appealing for everyday consumption but less desirable in terms of perceived nutritional value.

Real-Life Instances of Choosing Wild Foods

In some rural or indigenous communities, foraging for wild foods is a regular practice, as these populations understand the superior nutritional value of naturally grown produce. In contrast, urban dwellers may rely on mass-produced fruits and vegetables, which, while convenient, lack the nutrient density found in their wild counterparts. Many health enthusiasts now seek out wild-grown or minimally cultivated foods for their diets, especially as part of movements like “farm-to-table” or “foraging” trends.

Actionable Steps to Implement This Knowledge

Incorporate Wild or Organic Foods: Where possible, opt for wild-harvested or organic varieties of fruits, vegetables, and nuts to ensure higher nutrient intake.

Try Foraging: If safe and legal in your area, learn to identify and forage wild foods like berries or nuts. Start small and always consult a guide or expert before consuming unfamiliar plants.

Support Local, Small-Scale Farmers: Choose produce from local farmers who use natural, less-intensive farming methods. These foods are often closer to their wild counterparts than heavily farmed, mass-produced options.

By embracing wild and naturally grown foods, individuals can access richer, more nourishing produce that supports optimal health and well-being.

Conclusion

Understanding nature’s design provides valuable insight into identifying truly nutritious foods. By observing natural indicators such as flavor, color, difficulty in access, and the growing conditions of plants, we can make more informed choices about what we consume. Nature has designed foods that are both delicious and beneficial for our health, disproving the common belief that healthy foods must be bland or difficult to enjoy. The balance of consuming nutrient-dense foods alongside lighter options ensures optimal digestion and long-term well-being.

By embracing these simple guidelines, we reconnect with nature’s wisdom, allowing us to choose foods that nourish both our bodies and our senses.

Support Meda Foundation

This article, like many others, has been made possible by the generous support of patrons. If you found this article informative or useful, please consider donating to the Meda Foundation to help us continue our work. Additionally, we welcome you to share your knowledge and experiences through our feedback form. Your insights contribute to a growing community dedicated to better health and nutrition!

Resources for Further Research

Nutritional Density and Food Flavors

Color and Nutrient Content

Hard-to-Access Foods

- Blog: https://www.mindbodygreen.com/articles/the-nutritional-value-of-wild-and-foraged-foods

- Documentary: https://www.netflix.com/title/80198200 (Chef’s Table: Foraging episode)

Wild Foods and Uninfluenced Growth

- Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OVnJXwz3VCM (Wild Foods: A Richer, More Nutrient-Dense Alternative)

- Article: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/09/180905101422.htm

Food Resembling Human Body Parts

Balancing Heavy and Light Foods