Despite decades of international aid and trillions of dollars in development programs, poverty persists in many regions, not because of a lack of resources, but due to flawed systems, misaligned incentives, and institutional control. From conditional lending and structural adjustment programs to tied aid and the sprawling aid-industrial complex, foreign assistance has often fostered dependency, undermined local governance, and eroded social and cultural resilience. Real progress emerges when nations prioritize internal reform, empower local entrepreneurship, invest in human capital, and engage in fair trade, while technology and grassroots innovation amplify self-reliance. Breaking the cycle of poverty requires rethinking aid as a tool for empowerment rather than control, fostering ecosystems where communities can thrive with dignity, autonomy, and sustainable prosperity.

Perpetuating Poverty – Why Aid Fails and How to Break Free

I. Introduction: The Paradox of Development Aid

For more than seven decades, the world has rallied around the promise of development aid. Trillions of dollars have flowed from wealthy nations and multilateral institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) into the coffers of governments across the developing world. The intention was noble: to accelerate growth, reduce poverty, and ensure that no nation was left behind in the march of progress. Yet, the sobering reality is hard to ignore—despite this massive financial infusion, vast populations across Africa, Latin America, South Asia, and parts of the Middle East remain trapped in poverty, weighed down by debt, and caught in cycles of corruption and underdevelopment.

This paradox forces us to confront a difficult question: Is aid helping, or is it perpetuating poverty? The answer is not straightforward. On the one hand, aid has undeniably provided emergency relief during famines, natural disasters, and wars. It has built schools, roads, and clinics, and in some cases, saved millions of lives. On the other hand, decades of evidence reveal a troubling pattern—aid often creates dependency rather than empowerment, displaces local initiative, props up authoritarian regimes, and distorts economic incentives in ways that make long-term development harder, not easier.

The issue is not merely economic—it is political, cultural, and deeply psychological. When governments become more accountable to international donors than to their own citizens, the social contract fractures. When communities learn to look outward for solutions rather than inward for resilience, the capacity for self-sufficiency erodes. And when global institutions impose “one-size-fits-all” prescriptions on vastly different societies, they risk undermining the very fabric of local agency and dignity.

This article is written for those who have a stake in this debate: policymakers who shape aid packages, economists who analyze their impact, NGO leaders and social entrepreneurs who work on the ground, donors who fund initiatives, and citizens who care about justice and prosperity. The goal is not to dismiss aid wholesale, nor to paint global institutions as villains. Instead, it is to critically examine how well-intentioned mechanisms have entrenched cycles of poverty—and to explore new models that prioritize empowerment, self-reliance, and human dignity over dependency.

The thesis is stark yet essential: Aid systems, dominated by the World Bank and IMF, often reinforce dependency, distort incentives, and undermine local capacities, making poverty a permanent condition instead of a solvable challenge. Unless the global community reimagines development beyond the narrow lens of financial transfers, the paradox will persist—billions spent, yet billions still poor.

II. Historical Background: From Colonialism to Aid Dependency

A. Colonial Legacies

The roots of today’s development challenges run deep into the soil of colonial history. For centuries, much of Africa, Asia, and Latin America functioned not as independent economies but as resource appendages for imperial powers. Colonies were rarely developed to serve their own people; instead, they were designed to extract raw materials—cotton, rubber, gold, sugar, oil—and to serve as captive markets for manufactured goods from Europe and North America. This extractive model left behind economies heavily dependent on a narrow range of exports, fragile political institutions, and social divisions deliberately fostered by colonial rulers.

When political independence arrived in the mid-20th century, many nations inherited borders drawn by outsiders, economies distorted toward extraction rather than diversification, and governance systems ill-equipped to manage inclusive development. The transition from political colonization to economic dependency was almost seamless. Where imperial administrators once dictated trade flows, international lenders and aid donors began to dictate economic policy. The logic of control shifted—but the imbalance remained.

B. Rise of Development Institutions

The next chapter in this story unfolded at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in 1944. As World War II neared its end, the Allied powers sought to build a new financial architecture that would stabilize currencies, rebuild war-torn Europe, and prevent another global depression. Out of this vision emerged two institutions that still dominate the development landscape: the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank.

Initially, their missions were limited and pragmatic. The IMF was tasked with ensuring monetary stability and short-term balance-of-payments support, while the World Bank (then the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development) was meant to finance Europe’s post-war reconstruction. Yet, as Europe recovered—through the Marshall Plan and domestic reforms—the institutions redirected their gaze toward the “developing world.” By the 1960s, they were deeply embedded in global poverty management, extending loans and designing policies for countries across Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

This shift marked a profound transformation: what began as a system for rebuilding industrialized economies became the backbone of development policy for nations with entirely different historical, cultural, and economic contexts. The tools and assumptions of Bretton Woods were never tailored for fragile post-colonial states, yet they were applied wholesale, often with damaging consequences.

C. Aid as Soft Power

It would be naïve to imagine that aid was ever a purely humanitarian enterprise. From the Cold War onward, aid became a powerful instrument of soft power. The United States and the Soviet Union funneled resources into allied states to secure loyalty, open markets, and maintain spheres of influence. Roads, dams, and schools were built, but so were military bases and authoritarian regimes. In Africa, leaders who pledged allegiance to either superpower were often rewarded handsomely, regardless of their record on governance or human rights.

This logic persists even in today’s ostensibly “neutral” aid. Donor countries often tie assistance to the purchase of their own goods and services, ensuring that a significant share of aid money circles back to their own industries. Aid flows can be conditioned on aligning with geopolitical priorities—supporting wars, opening markets to foreign corporations, or voting a certain way in international bodies. In this sense, “development” has too often been the polite packaging for strategic self-interest.

This historical backdrop is essential: poverty in many nations cannot be understood simply as the failure of local leaders or communities. It is the product of structural weaknesses born of colonial extraction, reinforced by international institutions, and manipulated through aid as a tool of influence. Understanding this trajectory sets the stage for examining the paradox of aid more critically—how systems meant to uplift often deepen dependency instead.

III. The Myth of Aid Effectiveness

A. Aid as a Noble Promise

Development aid was born out of lofty aspirations. After World War II, the vision of a more just and equitable world inspired donor countries and international institutions to commit resources to “lift nations out of poverty.” The moral argument was compelling: wealthy nations that had benefited from industrialization and global trade had both a responsibility and a strategic interest in supporting poorer countries. Aid would build schools and hospitals, improve agricultural productivity, modernize infrastructure, and seed the foundations of prosperity.

For decades, policymakers, economists, and philanthropists repeated the promise: with enough aid, poverty would decline, growth would flourish, and societies would stabilize. Aid was not just seen as charity; it was framed as an investment in shared global progress. It carried with it a sense of inevitability—that if rich nations transferred sufficient resources, poor nations would naturally follow the same development trajectory.

B. Ground Reality

The record, however, tells a sobering story. Despite trillions of dollars in aid since the mid-20th century, the impact on long-term growth rates has been minimal. While aid often addresses immediate needs—disaster relief, disease eradication, short-term budgetary support—its role in generating sustained economic development remains weak.

Instead, evidence shows the rise of aid dependency cycles. Countries receiving consistent inflows of aid often adapt their economies and governance structures around these flows, rather than developing domestic revenue systems or building resilient institutions. Governments prioritize donor relationships over citizen accountability, since political survival hinges more on external funding than on tax collection or voter approval. Over time, aid becomes less a tool for development and more a financial lifeline—difficult to escape, but equally difficult to build upon.

Worse still, aid inflows can distort local economies. When external funds pour into a country, they can artificially inflate currencies (the so-called “Dutch disease”), making local exports less competitive. Large-scale aid projects may also displace local industries, weaken entrepreneurial incentives, and foster corruption by concentrating resources in the hands of elites. The result is a paradox: while aid is supposed to accelerate growth, it often entrenches stagnation.

C. Illustrative Cases

The contrast between Africa and East Asia offers a telling lesson. Since the 1960s, Africa has received enormous volumes of aid, often accounting for 10–15% of GDP in some countries. Yet, living standards in many African nations have either stagnated or declined, with large portions of the population still lacking access to clean water, stable electricity, or quality education. While aid has provided temporary relief, it has not catalyzed structural transformation.

Now compare South Korea and Ghana. In the early 1960s, both nations had similar income levels, agricultural economies, and aspirations for modernization. Ghana, a recipient of significant aid, became emblematic of Africa’s “development project,” while South Korea, though receiving some support, relied heavily on domestic reforms, export-oriented policies, and disciplined investment in education and industry. Today, South Korea is one of the world’s most advanced economies, while Ghana, despite progress in recent decades, still grapples with poverty and underdevelopment. The divergence illustrates a central truth: aid alone does not create prosperity; internal reforms, local ownership, and institutional strength do.

The myth of aid effectiveness lies not in denying that aid has saved lives or provided essential relief—it has. The myth lies in the assumption that aid, in its current form, can engineer development. Evidence suggests that without addressing structural incentives, governance, and self-sufficiency, aid risks becoming a sedative: numbing the symptoms of poverty while allowing its deeper causes to fester.

IV. The World Bank and IMF: Institutions of Control

A. Conditional Lending

Perhaps no aspect of international development has been more controversial than the lending practices of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). When countries face fiscal crises, balance-of-payment deficits, or urgent budgetary shortfalls, these institutions step in with loans. On paper, this looks like a safety net; in practice, it often comes with heavy strings attached.

The central mechanism has been the Structural Adjustment Program (SAP). To qualify for loans, countries were required to implement sweeping reforms: cut spending on education, healthcare, and welfare; privatize state-owned enterprises; liberalize trade; and deregulate markets. These policies were based on the “Washington Consensus”—a set of free-market prescriptions designed in Western capitals but imposed on fragile economies without sufficient regard for local realities.

The results were often devastating. Cuts to public spending meant overcrowded schools, underfunded hospitals, and reduced safety nets for the poor. Privatization frequently transferred public assets into the hands of politically connected elites, while market liberalization exposed weak domestic industries to global competition they were ill-equipped to withstand. What was intended as economic reform became, in many cases, economic shock therapy, with ordinary citizens bearing the brunt of the pain.

B. Debt Traps

If the intent of these programs was to stabilize economies and reduce poverty, the evidence suggests otherwise. Instead of fostering resilience, many countries became ensnared in debt traps. Loans meant to solve short-term liquidity problems often created long-term financial burdens. As new loans were taken to service old ones, debt spiraled, and interest payments consumed increasing portions of national budgets.

The scale of the problem is staggering. Take Zambia as a case in point. By the 1990s, Zambia was spending more on servicing its external debt than on health and education combined. Entire generations grew up in a country where resources that could have built schools or supplied medicines were instead funneled back to creditors in Washington, London, and Paris. Far from solving poverty, debt repayments reinforced it, leaving nations locked in a cycle of borrowing and austerity with little room for domestic investment.

This cycle is not limited to Zambia. Across sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and parts of Asia, countries have struggled with debts so large that the idea of “development” often feels secondary to the imperative of repayment. For many citizens, the IMF and World Bank became less symbols of support and more symbols of perpetual financial subjugation.

C. Sovereignty Undermined

Beyond the economic numbers lies a deeper issue: sovereignty. When a nation’s fiscal and monetary policies are effectively dictated by loan conditions, who truly governs? Elected officials may hold office, but the real power often resides in the boardrooms of Washington, D.C. or Geneva.

The so-called Washington Consensus—privatization, liberalization, deregulation—became a universal prescription, regardless of whether it matched the social, cultural, or economic fabric of the recipient nation. Local voices, community leaders, and even national parliaments were sidelined in the name of technocratic efficiency. Policies that should have been crafted through democratic debate were instead signed off under the pressure of conditional lending.

This undermining of sovereignty carries long-term consequences. Citizens lose faith in governments that appear to serve foreign creditors rather than domestic needs. Political instability often follows, with cycles of unrest, coups, or populist backlash. At its core, the issue is not just about money—it is about dignity, agency, and the right of nations to chart their own futures without external puppeteering.

In theory, the World Bank and IMF exist to stabilize economies and promote development. In practice, their policies have too often entrenched dependency, hollowed out institutions, and eroded sovereignty. For millions across the Global South, these institutions are less remembered for building stability than for deepening poverty under the guise of reform.

V. The Politics of Poverty

A. Who Really Benefits?

When development aid is announced, the public image is often one of altruism: wealthy nations extending a helping hand to poorer ones. Yet beneath the surface lies a complex web of interests. Aid is rarely neutral. In many cases, the primary beneficiaries are not the citizens of recipient countries but the institutions and corporations of donor nations.

A significant share of aid is tied to contracts requiring that recipient governments purchase goods and services from companies in donor countries. This ensures that billions in aid effectively flow back to Western construction firms, engineering consultancies, and technology suppliers. A highway in Africa may carry the stamp of foreign aid, but the profits from its construction often end up in New York, London, or Paris.

The “development industry” itself has become a lucrative career path. Bureaucrats and consultants from donor countries, often earning salaries far exceeding local standards, travel the globe conducting studies, drafting reports, and implementing projects. While some bring valuable expertise, others perpetuate a system in which development becomes a business model. Poverty, paradoxically, sustains employment for armies of well-meaning professionals whose livelihoods depend on its persistence.

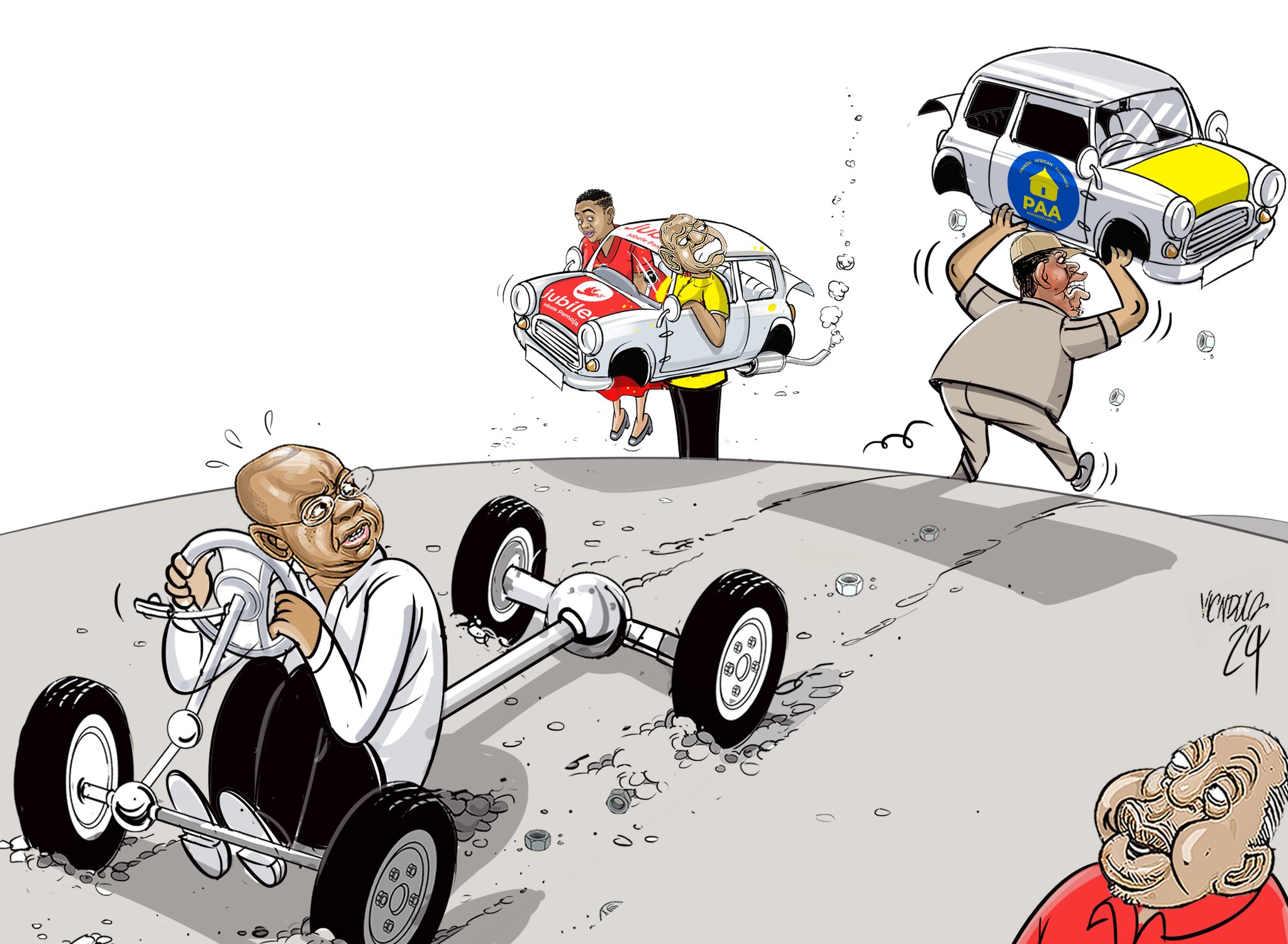

B. Domestic Corruption

The dysfunction does not end at donor borders. In recipient countries, aid funds frequently fall prey to corruption. Instead of reaching schools, clinics, or farmers, money is siphoned off by political elites. Ruling classes capture aid as a resource for patronage—rewarding allies, buying loyalty, or even enriching themselves directly.

The phenomenon of “phantom projects” is all too common: a hospital may exist on paper, complete with allocated budgets and international approval, but the building never materializes. Roads are inaugurated but remain incomplete. In some cases, funds are diverted into offshore accounts, fueling a cycle where aid intended for development ends up financing luxury villas, foreign investments, or political campaigns.

This corruption not only wastes resources but also deepens inequality. Ordinary citizens are left with unmet needs while elites tighten their grip on power, insulated by the very funds that were meant to reduce poverty.

C. The Accountability Gap

At the heart of the politics of poverty lies a profound accountability gap. In functioning democracies, governments are accountable to their citizens, dependent on taxes for revenue and votes for legitimacy. But when aid flows constitute a large share of a nation’s budget, this accountability is disrupted. Governments become more responsive to donor agencies than to the people they ostensibly serve.

Instead of designing policies through consultation with local communities, leaders tailor strategies to meet donor requirements—focusing on what looks good in reports rather than what works on the ground. This creates perverse incentives: leaders who fail their citizens can still secure international legitimacy so long as they maintain donor relationships. Meanwhile, citizens lose faith in institutions that seem unresponsive to their realities.

The tragedy is that aid, intended to strengthen governance, often weakens it. By shifting accountability away from citizens and toward external actors, aid distorts the very foundations of political legitimacy. Poverty, in this context, is not just an economic condition but a political outcome—sustained by systems that reward dependency and disempower democratic accountability.

VI. Social and Cultural Costs of Aid

A. Dependency Mentality

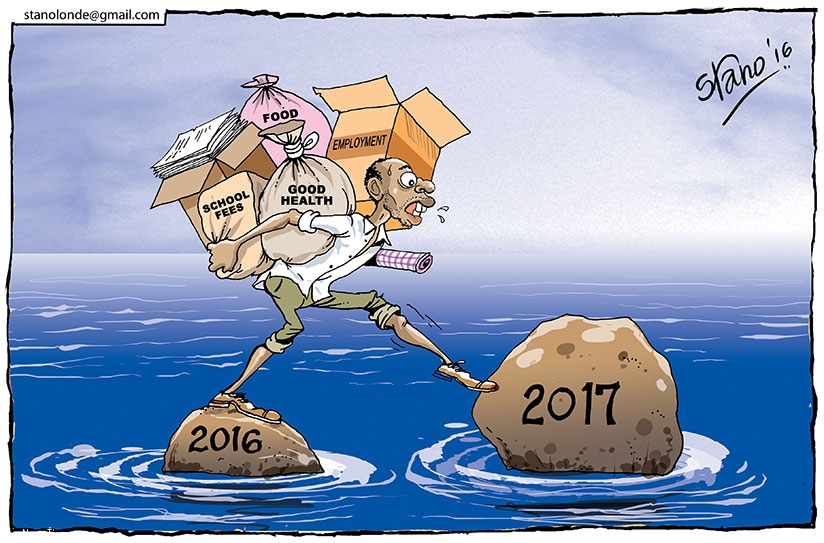

One of the least acknowledged but most damaging consequences of aid is the psychological conditioning it creates. When citizens see their governments habitually turning to the World Bank, the IMF, or bilateral donors for solutions, a message is subtly reinforced: salvation lies outside, not within.

Over time, this breeds a dependency mentality. Local populations begin to expect foreign intervention for everything from food security to education, rather than cultivating indigenous solutions. Even governments internalize this mindset, treating aid as a permanent revenue stream instead of a temporary support mechanism.

The result? Local innovation is suppressed. Communities that once developed creative ways to deal with scarcity—rotating credit associations, cooperative farming, indigenous medicinal practices—now see those methods devalued or abandoned in favor of externally funded programs. Instead of unleashing entrepreneurship, aid unintentionally narrows the scope of imagination to what donors are willing to fund.

B. Weakening Social Bonds

Traditional societies often relied on reciprocity and collective responsibility as survival strategies. For example, African villages had “work parties” where neighbors helped build each other’s homes; Indian communities relied on shramdaan (voluntary collective labor) for irrigation or temples. These practices were not just economic tools but cultural anchors, binding people together through shared responsibility.

But large-scale aid projects, channeled through governments or NGOs, gradually displace these local systems. Why join a community effort when an international donor is building a school or clinic? Why rely on neighbors when outside funds provide subsidies or handouts?

This shift undermines social capital—the trust, reciprocity, and collective agency that hold communities together. Once eroded, these bonds are difficult to restore, leaving societies more fragmented and individuals more isolated.

C. Psychological Erosion

Perhaps the deepest wound aid leaves is not economic or political but psychological. Aid frameworks often present poverty not as a temporary challenge but as a permanent condition requiring external rescue. The poor are subtly redefined as helpless recipients rather than resilient actors.

This narrative corrodes dignity. A farmer who once saw himself as a provider now sees himself as a “beneficiary.” A nation proud of its heritage begins to internalize an identity of perpetual deficiency.

Worse still, aid often exports foreign values that don’t always align with local traditions. When metrics of “development” are dictated externally—measured in donor-defined indicators—people begin to view themselves through the lens of inadequacy. Poverty is no longer just about lack of resources; it becomes a state of the mind.

The long-term effect is a quiet erosion of self-belief. Generations grow up learning not that they can solve their own problems, but that they must wait for outsiders to do it for them. This is the most insidious poverty of all: a poverty of hope.

VII. The Aid-Industrial Complex

A. The Development Industry

Over decades, aid has evolved into a vast industry with its own rules, hierarchies, and self-interest. Donors, NGOs, international consultants, and think tanks form a self-perpetuating ecosystem that thrives on the continuation of poverty rather than its elimination. In this system, success is measured less by the eradication of poverty than by the disbursement of funds, the number of projects initiated, or the scope of influence achieved.

Careers are built on what might be called “poverty management.” Professionals travel from capital to capital, country to country, monitoring programs, attending donor meetings, and producing studies. While expertise is real, the incentives are misaligned: the fewer the systemic solutions, the greater the need for ongoing consulting, evaluation, and program implementation. Ironically, persistent poverty sustains a significant global workforce, making the eradication of poverty a potential threat to the livelihoods of those who work to address it.

B. The Illusion of Progress

Much of the development industry operates in symbolic spaces rather than on the ground. International conferences, glossy annual reports, and sophisticated dashboards give the appearance of progress, even when tangible results remain limited.

A village may receive a new school building funded by foreign aid, yet without local teachers, maintenance, or curriculum tailored to community needs, the school remains underutilized. Similarly, large-scale programs that distribute food, seeds, or technology often fail to foster long-term self-reliance, instead creating temporary relief that vanishes when donor funding ends.

This creates an illusion of progress: policymakers and donors can showcase activity and investment, but systemic poverty remains untouched. Meanwhile, communities adapt to project cycles rather than building resilience, reinforcing the perception that poverty can only be solved externally.

C. Aid as Business

In recent decades, philanthrocapitalism has reshaped the aid landscape. Wealthy individuals, corporations, and foundations inject billions into development initiatives, often guided by business models emphasizing efficiency, measurable outputs, and innovation. On paper, this approach promises more accountability and better outcomes.

In reality, aid money frequently cycles back into corporate interests. Donors fund contracts, technology, and consultancy services that primarily benefit firms from donor countries. While development outcomes may improve incrementally, the financial flows ensure that aid functions as both a moral endeavor and a business opportunity. In effect, poverty funds part of the global economy, creating a market where charitable impulses are entwined with profit.

The aid-industrial complex illustrates a central paradox: while billions are dedicated to ending poverty, the very structure of the system often ensures its persistence, sustaining careers, businesses, and institutions that rely on the continuation of dependency. The challenge, therefore, is not just the allocation of aid but the redesign of the incentives that govern its flow.

VIII. The Cost of Structural Adjustments

A. Social Devastation

Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs), introduced by the IMF and World Bank as conditions for lending, were intended to stabilize economies and promote growth. In practice, however, they often inflicted severe social costs on the most vulnerable populations.

By enforcing spending cuts, SAPs led to widespread job losses in public sectors, undermining the very institutions meant to support citizens. Inflation frequently surged as subsidies were removed and currencies adjusted, eroding the purchasing power of ordinary families. Public safety nets—pensions, welfare programs, food subsidies—collapsed under fiscal austerity, leaving millions exposed to hunger, unemployment, and insecurity.

Communities that once relied on government programs for basic services suddenly found themselves navigating a harsher, privatized landscape. The intended “efficiency” often translated into social dislocation, heightening inequality, and fueling political unrest.

B. Educational and Health Crises

SAPs also reshaped the human development landscape in ways that continue to reverberate today. To reduce public expenditures, many countries introduced user fees for education and healthcare, effectively pricing out the poorest segments of the population. Children from low-income families were forced to drop out of school, while families deferred or avoided medical care due to cost.

The long-term impact is stark. Educational attainment stagnated, literacy rates slowed, and health outcomes deteriorated, particularly among vulnerable populations such as women and children. Even when aid-funded schools or clinics were built, their accessibility remained limited, undermining the very purpose of international development efforts.

C. Generational Impacts

Perhaps the most insidious effect of structural adjustment is its intergenerational consequences. When young people are denied quality education, healthcare, and vocational training, their potential to contribute productively to the economy diminishes. Skills, innovation, and human capital—all crucial for long-term development—are stunted.

Entire generations grow up with reduced opportunities, often trapped in cycles of low-wage work, precarious employment, or informal labor markets. The human cost of SAPs is therefore not just measured in immediate deprivation but in lost potential: young people unable to escape poverty become the foundation for a society structurally constrained by underdevelopment.

Structural adjustment, designed as a technical solution to economic imbalance, thus translates into human suffering, weakened institutions, and stunted national growth. The irony is striking: in seeking fiscal discipline and stability, SAPs frequently eroded the very social and human capital needed for sustainable development.

IX. Rethinking Development: From Dependency to Empowerment

A. Internal vs. External Drivers

History shows that sustainable development rarely emerges from external aid alone. Nations that have achieved rapid and enduring growth often relied on internal reform, domestic investment, and strategic governance rather than foreign assistance.

Take East Asia as a prime example. South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore in the latter half of the 20th century pursued export-oriented industrialization, invested heavily in education, and implemented land and labor reforms. While some aid was received, it was secondary to internal drivers of growth: strong institutions, merit-based bureaucracy, and policies designed to nurture domestic industries. These countries illustrate a critical principle: development succeeds when citizens and governments prioritize local capacity, ownership, and accountability.

Contrast this with countries that became heavily aid-dependent. Here, external funding often substituted for domestic reforms, creating short-term improvements but failing to establish the institutional foundations needed for long-term resilience. Aid cannot substitute for self-determination and internal initiative; it can only supplement them.

B. Empowering Local Entrepreneurship

A core pathway to breaking cycles of dependency is the empowerment of local entrepreneurship. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs), cooperatives, and community-driven initiatives are the engines of sustainable development when they are given resources, training, and autonomy.

Microfinance, pioneered in Bangladesh and elsewhere, demonstrates how targeted financial support can enable individuals to start businesses, build livelihoods, and reinvest in their communities. Cooperatives in sectors like agriculture, handicrafts, and energy allow communities to pool resources, share risks, and capture more value locally.

Empowerment is not about charity; it is about creating systems where people solve their own problems, where profits and benefits remain within communities, and where dependency on external funding gradually diminishes. Education, mentorship, and access to technology amplify these effects, enabling local actors to innovate and scale solutions tailored to their own realities.

C. Trade over Aid

Finally, a shift from aid to trade-based development offers a structural solution to dependency. Open and fair markets allow nations to leverage their comparative advantages, participate meaningfully in global value chains, and generate sustainable wealth.

Western agricultural subsidies, protectionist policies, and unfair trade barriers have historically undermined developing economies, preventing local farmers and producers from competing globally. Removing these distortions, while supporting infrastructure and skills development domestically, can create organic growth rather than relying on conditional aid.

Trade-driven approaches also incentivize efficiency, innovation, and competitiveness. Countries are no longer passive recipients of resources but active participants in global markets, building resilience and reducing vulnerability to external shocks. By combining trade with targeted support for domestic entrepreneurship, nations can shift from aid dependency to economic empowerment.

Conclusion of this Section:

Rethinking development requires moving beyond donor-centric models. True progress emerges when nations prioritize internal reform, local enterprise, and fair participation in global markets. Aid should complement, not substitute, these strategies. Empowerment—economic, social, and political—must replace dependency if cycles of poverty are to be broken.

X. New Pathways to Prosperity

A. Policy Recommendations

Breaking the cycle of aid dependency requires structural reforms at both the international and national levels. Policy interventions must shift from prescriptive, donor-driven programs toward strategies that prioritize sovereignty, accountability, and human development. Key recommendations include:

- Debt Forgiveness Linked to Governance Reforms

- Long-term indebtedness traps nations in cycles of poverty. Forgiving debt can free resources for public investment—but it must be coupled with transparent governance reforms, ensuring funds are allocated efficiently and equitably.

- Ending Tied Aid

- Donor countries often require that aid be spent on goods or services from the donor nation, reducing its effectiveness. Granting recipient autonomy allows governments to invest in local businesses, industries, and human capital, generating sustainable returns within the country.

- Investing in Human Capital

- Infrastructure projects are important, but long-term prosperity depends on education, healthcare, and skill development. Investing in teachers, healthcare workers, vocational training, and innovation ecosystems ensures that citizens are empowered to contribute productively to the economy.

B. Grassroots Innovations

Development must be rooted in local realities, leveraging community knowledge and social capital. Grassroots innovations demonstrate that solutions generated from within communities are often more resilient, scalable, and culturally appropriate than top-down interventions. Examples include:

- Education Systems Tailored to Local Realities

- Schools and curricula designed for specific communities—accounting for language, culture, and economic context—improve learning outcomes and foster long-term empowerment.

- Community-Led Energy, Food, and Tech Solutions

- Microgrids, cooperative farming, and local technology hubs illustrate how communities can address basic needs while generating income. These models reduce dependency on external aid and enhance resilience against environmental and economic shocks.

- Inclusive Governance Mechanisms

- Participatory budgeting, community councils, and local decision-making bodies ensure that development projects respond to real needs rather than donor priorities.

C. Role of Technology

Technology offers transformative tools for accelerating empowerment and bridging systemic gaps:

- Mobile Banking and Digital Finance

- Platforms like M-Pesa in Kenya show how financial inclusion can empower individuals, stimulate local economies, and reduce reliance on cash-based aid systems.

- AI and Data-Driven Solutions in Agriculture

- Digital platforms can optimize crop yields, predict market trends, and improve supply chain efficiency, allowing farmers to earn more and innovate independently.

- Healthcare Innovation

- Telemedicine, AI diagnostics, and remote monitoring systems extend quality healthcare to underserved areas, improving health outcomes without relying solely on foreign aid programs.

By combining policy reform, grassroots innovation, and technology adoption, nations can cultivate self-reliance, equitable growth, and durable prosperity. Aid, if properly structured, can play a supporting role rather than dominating the development process.

XI. Ethical and Philosophical Reflections

A. The Morality of Aid

At its core, aid raises profound moral questions. Is it a pure act of generosity, a sincere attempt to alleviate suffering? Or does it serve as a subtle form of control, imposing external values and priorities on vulnerable nations?

The evidence of tied aid, conditional loans, and policy prescriptions suggests that the line between charity and influence is often blurred. While saving lives and providing resources is unquestionably virtuous, the broader consequences—dependency, weakened institutions, and eroded sovereignty—invite a careful ethical examination. True morality in development may require restraint, humility, and respect for local agency rather than a relentless drive to “fix” problems according to external definitions of progress.

B. Justice vs. Charity

There is a crucial distinction between charity and justice. Charity is episodic, often temporary, and reinforces a donor-recipient hierarchy. Justice, by contrast, emphasizes equity, dignity, and empowerment.

Development rooted in justice focuses not on providing handouts but on creating conditions for self-reliance: access to quality education, fair markets, political accountability, and opportunities for entrepreneurship. Empowerment respects human dignity; it treats citizens as actors in their own development rather than passive recipients. True progress is measured not by the volume of aid disbursed but by the capacity of individuals and communities to thrive independently.

C. Global Responsibility

The ethical imperative for the global community extends beyond helping the poor—it is about dismantling the structures that perpetuate poverty. Historical exploitation, unequal trade systems, extractive debt arrangements, and foreign interference are barriers that prevent nations from achieving self-sufficiency.

Global responsibility, therefore, is not simply about sending resources; it is about restructuring relationships, reducing systemic inequities, and creating opportunities for autonomous growth. Developed nations, international institutions, and donors must recognize that aid should be a tool for liberation, not a mechanism of dependency. When framed in this light, development becomes a shared endeavor rooted in justice, solidarity, and mutual accountability.

Reflection:

Ethical development is not merely a technical exercise in resource allocation—it is a philosophical and moral commitment to respecting human agency, nurturing capacity, and dismantling barriers to opportunity. Aid, when misaligned with these principles, risks perpetuating cycles of poverty under the guise of benevolence. When aligned with justice, it becomes a catalyst for empowerment, dignity, and sustainable transformation.

XII. Conclusion: Breaking Free from the Aid Trap

Key Takeaway

Poverty is not primarily the result of a lack of resources. It is perpetuated by flawed systems, misaligned incentives, and institutional control—from colonial legacies to modern aid mechanisms, from debt traps to tied funding. Generations of development assistance have shown that well-intentioned aid, when poorly structured, can entrench dependency, distort local economies, and weaken both governance and social cohesion.

Forward Vision

The future of development lies not in the continuous flow of external aid, but in the cultivation of ecosystems of self-reliance, resilience, and human dignity. Nations and communities flourish when they are empowered to design their own solutions, leverage local innovation, and access fair trade opportunities. Education, healthcare, and technology should be enablers of autonomy, not instruments that bind citizens to external priorities. By prioritizing empowerment over charity, we create durable change that benefits current and future generations.

Call to Action

Ending cycles of dependency is not solely the responsibility of governments or international institutions—it requires collective participation. You can contribute by supporting initiatives that focus on local capacity-building, entrepreneurship, and sustainable solutions.

Participate and Donate to MEDA Foundation. Your support helps us implement programs where individuals and communities become truly self-sufficient, breaking free from systemic poverty and nurturing ecosystems of hope, opportunity, and dignity. Together, we can turn the promise of development into a reality that respects human potential rather than undermining it.

Book References

- Perpetuating Poverty: The World Bank, the IMF, and the Developing World – Doug Bandow & Ian Vásquez

- Dead Aid – Dambisa Moyo

- The White Man’s Burden – William Easterly

- Poor Economics – Abhijit Banerjee & Esther Duflo

- The Bottom Billion – Paul Collier

- Confessions of an Economic Hit Man – John Perkins