Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) is a hidden yet life-altering condition that affects how children interpret and respond to everyday sensations, often leaving them overwhelmed, misunderstood, and emotionally fragile. Rooted in neurological differences, SPD manifests in diverse ways—ranging from hypersensitivity to sensory-seeking behaviors—and disrupts routines at home, school, and in social settings. Understanding SPD requires not just clinical insight, but deep empathy and the willingness to see children not as “disordered,” but as uniquely wired. Through sensory-informed parenting, supportive classrooms, and compassionate societal systems, children can thrive, build resilience, and reclaim harmony in a world that often expects conformity. Empowering families, educators, and institutions to recognize and support sensory needs unlocks the hidden potential of every out-of-sync child—offering hope, healing, and a path toward inclusion and joy.

Understanding Sensory Processing Disorder: Insights from The Out-of-Sync Child

Intended Audience and Purpose of the Article

Audience

This article is designed for a broad yet deeply invested audience that touches the lives of children who experience the world through a different sensory lens:

- Parents and caregivers who love, raise, and support children navigating daily challenges due to sensory processing differences—often without clear guidance or validation.

- Educators, occupational therapists, pediatricians, and early interventionists who serve as the frontlines of support in diagnosing, accommodating, and empowering children with Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) or related neurodevelopmental conditions.

- Social entrepreneurs, policy advocates, and nonprofit organizations, particularly those focused on inclusion, mental health, neurodiversity, and child development, who seek systems-level insight and social innovation to create a world more attuned to invisible needs.

Purpose

The purpose of this article is threefold:

- To Illuminate

Many children with SPD go undiagnosed or are mislabeled with conditions that only scratch the surface—like “lazy,” “defiant,” “over-sensitive,” or “unmotivated.” This article brings SPD into the light by distilling key insights from The Out-of-Sync Child—a pioneering and compassionate book by Carol Stock Kranowitz—into a clear, accessible framework. We aim to demystify sensory differences and validate the very real struggles that these children and their families face. - To Equip

Information is not enough. Parents and educators often find themselves overwhelmed by contradictory advice, limited resources, or lack of practical tools. This article not only defines and contextualizes SPD but also provides concrete, field-tested strategies to help children thrive in school, at home, and in social settings. It will guide caregivers in building structured routines, sensory-safe environments, and emotionally attuned relationships that support sensory regulation and resilience. - To Advocate and Transform

A child with SPD doesn’t need to be “fixed.” What must change is our collective mindset—how society accommodates invisible neurological diversity and how we design environments, curricula, and support systems that acknowledge and empower the “out-of-sync” child.

This article makes a strategic and moral case for inclusive practices, better early screening, community-wide education, and policy shifts that respect sensory differences as legitimate human variation. It seeks to build systemic empathy—where love meets action, and understanding becomes infrastructure.

Ultimately, the article aspires to foster a paradigm shift:

From “What’s wrong with this child?”

To “What does this child need from us, and how can we adapt with grace?”

By interweaving neurodevelopmental science, practical parenting wisdom, educational design, and socio-cultural reflection, this article will serve as a comprehensive guide and gentle companion for anyone invested in the flourishing of children who experience the world out-of-sync—but never out of hope.

Key Takeaways

The heart of this article is not in diagnosing or defining a disorder—it is in changing how we see, support, and stand beside children who experience the world differently. Before we dive deep into the what, why, and how of Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD), here are the four transformative insights that frame our entire discussion:

1. Sensory Processing Disorder is real, invisible, and profoundly affects children’s ability to function and relate.

SPD is not a parenting issue. It is not misbehavior. It is not a phase. It is a neurological condition that alters how the brain receives, interprets, and responds to sensory input—from light, sound, and textures to movement, pressure, and internal body signals. What looks like stubbornness or anxiety may actually be a child fighting to survive overwhelming sensory chaos.

Because SPD is not formally recognized in many diagnostic manuals (such as the DSM-5), it often falls through the cracks—leaving children misunderstood and unsupported. We must recognize this condition as real and impactful, even if invisible to the untrained eye.

2. Recognizing sensory differences early enables tailored support that leads to better emotional, social, and academic outcomes.

Early identification is everything. When SPD is caught and addressed in early childhood, the potential for adaptive growth is tremendous. With targeted therapies, structured environments, and sensory-informed parenting, children can learn to self-regulate, connect with others, and engage meaningfully with the world around them.

Delays in recognition can lead to compounding problems: low self-esteem, academic failure, social withdrawal, and secondary mental health issues. Proactive support can break this cycle and replace it with one of trust, confidence, and progress.

3. Empowerment lies in education, compassionate routines, and sensory-informed communities—not in judgment or labeling.

SPD is not a flaw to be fixed—it is a difference to be understood. Our power lies in building systems of support rather than systems of shame. This means:

- Educating families, teachers, and peers about sensory needs

- Creating predictable routines and sensory-safe spaces

- Allowing movement, choice, and sensory tools in learning environments

- Training professionals to recognize and honor sensory signals

We must shift from compliance-based parenting and teaching to connection-based collaboration, where children feel safe enough to grow at their own pace.

4. Every “out-of-sync” child has hidden brilliance when seen through the right lens.

What appears chaotic on the surface—restlessness, meltdowns, avoidance, “quirkiness”—is often the outer expression of an inner storm. But within that storm lies creativity, insight, sensitivity, intuition, and innovation.

Many of the world’s most impactful creators, scientists, artists, and thinkers have walked this path. The goal is not to push children into neurotypical molds but to cultivate their unique strengths in ways that honor their neurology.

When we shift our lens, we stop trying to fix the child—and instead begin to fix the environments, attitudes, and systems that fail to see them.

These four takeaways are more than summary points. They are a moral framework for how we can move forward—together—toward a world that values every child, in sync or not.

1. Introduction: The Unseen Struggle of Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD)

In a world wired for sameness—where children are measured by how well they sit still, follow instructions, color inside the lines, and smile on cue—there exists a quieter, more complex narrative. It belongs to the child who flinches at the buzz of fluorescent lights, who melts down at the scratch of a clothing tag, who spins in circles just to feel grounded, who is labeled “too sensitive,” “too wild,” “too much.” This is the out-of-sync child—a term lovingly coined by educator and author Carol Stock Kranowitz, whose work has illuminated a world many could not see before.

Being “out-of-sync” does not mean being broken. It means that the child’s nervous system is processing the world in a way that does not align with expected norms—especially in environments that demand conformity over curiosity, speed over sensitivity, and silence over self-expression. For these children, the daily act of functioning—dressing, eating, playing, learning, listening—is not effortless. It is exhausting.

Why SPD is Often Misunderstood or Misdiagnosed

Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) does not come with visible markers. There is no blood test. No cast. No wheelchair. The child appears “normal,” and this very invisibility becomes its own trap. Without visible proof, parents are often blamed, educators grow impatient, and clinicians struggle to place the child within neat diagnostic boxes.

SPD is frequently misread as ADHD, oppositional defiance, anxiety, or even autism spectrum disorder (ASD). While it may coexist with any of these, SPD is distinct in that it centers on how the brain interprets and responds to sensory input—not necessarily on attention, cognition, or language per se. It is an issue of neurological traffic control: too much input, too little filtering, too many signals, or too much silence in the system.

This misunderstanding is not just clinical—it’s deeply emotional. Parents of out-of-sync children are often judged, isolated, and desperate for answers. The child, meanwhile, internalizes frustration, rejection, and confusion, unsure why their experience of the world is so different—and why the world doesn’t understand.

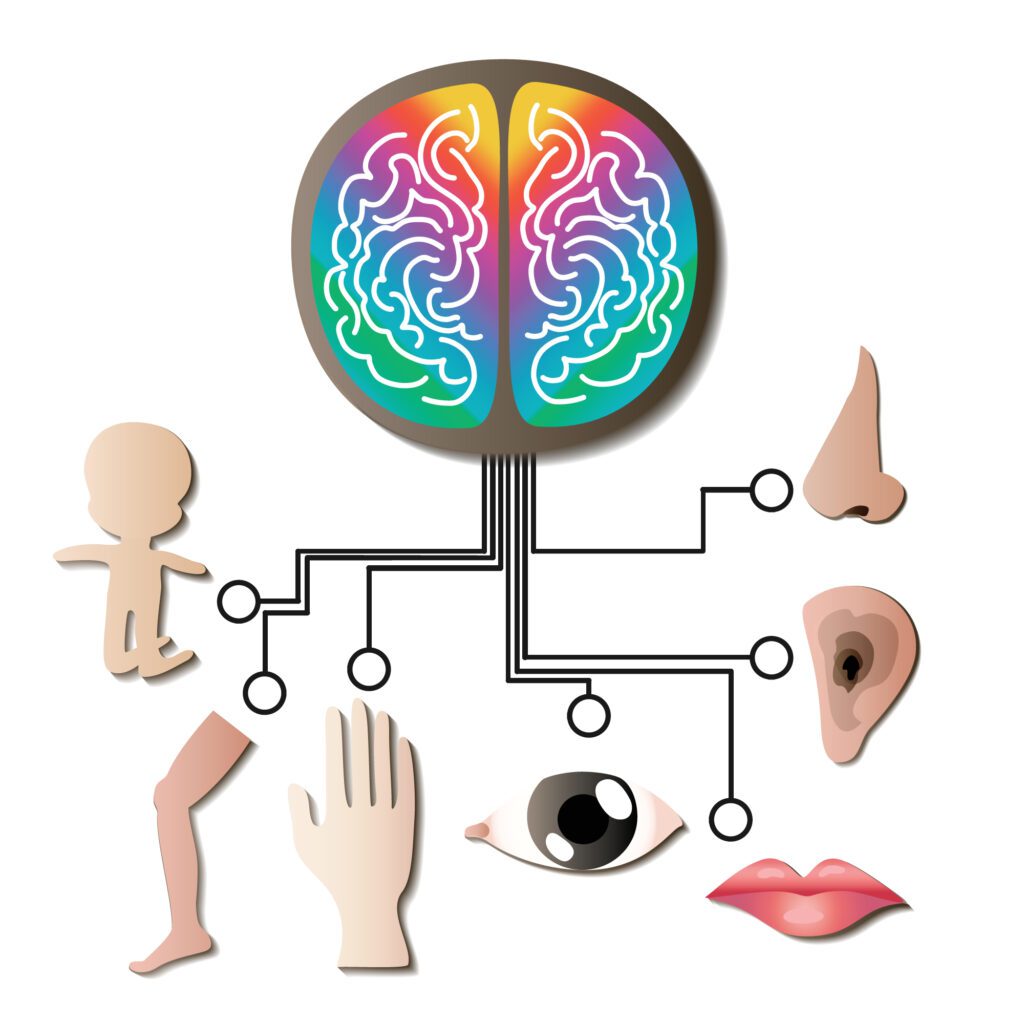

The Importance of Sensory Integration in Human Development

Sensory integration—the brain’s ability to take in sensory input, make sense of it, and respond appropriately—is foundational to everything we do. From the moment we are born, our senses guide our motor development, emotional regulation, social bonding, learning, and even identity formation.

Touch calms the newborn. Vestibular input (balance and movement) teaches a toddler how to walk. Proprioception (body awareness) helps a preschooler climb without falling. The ability to filter out background noise allows a student to focus in class. When this integration is disrupted, the consequences ripple across every domain of development:

- A child may gag at food textures and become a picky eater, risking nutritional issues.

- Another might overreact to a gentle touch and push others away, misinterpreted as “aggressive.”

- Yet another may seem disinterested in learning—not from lack of intelligence, but from sensory overload.

Sensory processing is not an “extra” feature of human development—it is its foundation. When that foundation is shaky, so is everything built on top of it.

Framing Through Kranowitz’s Lens: Love, Advocacy, and Hope

Carol Stock Kranowitz—a former preschool teacher turned advocate—did not write The Out-of-Sync Child as a medical treatise. She wrote it as a call to awareness and action born out of love for misunderstood children. Her lens is both compassionate and empowering. She invites us not to pathologize difference, but to understand it. Not to control children, but to connect with them. Not to fix them, but to support them in syncing with the world at their own rhythm.

Kranowitz teaches that while sensory challenges are real and sometimes overwhelming, they are not destiny. With the right knowledge, tools, and community support, children with SPD can flourish. Their struggles do not define them—their potential does.

This article adopts Kranowitz’s frame wholeheartedly. It seeks to be a guide, not a manual; a mirror, not a microscope. We walk alongside the out-of-sync child with humility, curiosity, and deep respect. We speak not only to therapists and teachers, but to parents on the edge of burnout, to neighbors who’ve seen the meltdown in aisle five, and to anyone willing to see the invisible with new eyes.

Because the truth is: it’s not the child who is out-of-sync with the world.

It is often the world that is out-of-sync with the child.

2. What is Sensory Processing Disorder?

Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) is not a behavioral problem. It is not simply a preference for quiet, an aversion to textures, or a dislike for crowds. It is a neurological condition that affects how the brain receives, organizes, and responds to sensory information—touch, sound, sight, taste, smell, movement, body awareness, and internal cues. When this process is disrupted, the child’s ability to function, focus, relate, and self-regulate is deeply affected.

Think of the brain as an orchestra conductor. When sensory input floods in, the brain’s job is to organize the instruments (sights, sounds, touches, smells), balance them, and produce a harmonious response. In SPD, the conductor may be missing a score, mishearing cues, or overreacting to the violins while ignoring the drums. The result is dissonance—a sensory world that feels too loud, too bright, too itchy, too fast, or not enough.

How SPD Differs from Autism, ADHD, and Learning Disabilities

SPD often coexists with other developmental conditions—but it is not synonymous with them:

- Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): While over 90% of individuals with autism show sensory challenges, not all children with SPD are on the spectrum. SPD does not necessarily affect social reciprocity, communication, or imagination—the hallmark traits of autism.

- ADHD (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder): Children with SPD may appear hyperactive or inattentive, but the root cause is often sensory overload or under-stimulation, not necessarily deficits in attention regulation.

- Learning Disabilities: While SPD can impact reading, writing, or math performance, it does not stem from cognitive impairment. Rather, disrupted sensory input can make the act of learning itself overwhelming or inaccessible.

In short, SPD is about how the brain processes sensation, not how it reasons, speaks, or learns—though it inevitably touches all of those areas.

The Neurological Basis of SPD

The brain processes sensory input through a complex network involving the thalamus, brainstem, cerebellum, and sensory cortices. When functioning well, these systems work together to:

- Prioritize relevant stimuli

- Filter out background “noise”

- Translate sensation into appropriate emotional and motor responses

In SPD, this sensory highway becomes jammed, rerouted, or unresponsive. A child might scream at the sound of a vacuum cleaner (hypersensitivity), not notice a scraped knee (hyposensitivity), or crash into furniture in search of feedback (sensory-seeking behavior).

Dr. A. Jean Ayres, the pioneer of sensory integration theory, described SPD as a “traffic jam in the brain”—where messages don’t get where they need to go, or they arrive garbled.

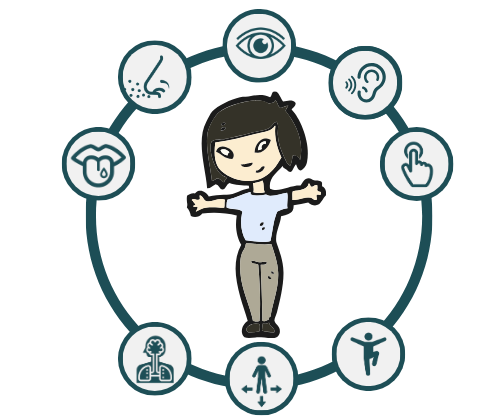

The Eight Senses Involved in Sensory Processing

We are taught there are five senses. In truth, we have at least eight, and all are essential for self-regulation and functioning:

- Sight (Visual): Perceiving and processing light, color, and motion

- Sound (Auditory): Hearing and filtering volume, pitch, and background noise

- Touch (Tactile): Interpreting textures, temperatures, pressure

- Taste (Gustatory): Sensing flavors and textures of food

- Smell (Olfactory): Detecting odors and their meanings (e.g., danger, comfort)

- Proprioception (Body Awareness): Knowing where your body is in space—crucial for movement, coordination, and calmness

- Vestibular (Balance and Motion): The sense that tells us whether we’re upright, moving, spinning, or still—key for spatial orientation and stability

- Interoception (Internal Body Signals): Awareness of internal states such as hunger, thirst, temperature, and the need to use the toilet

Many children with SPD struggle most with the “hidden senses”: proprioception, vestibular, and interoception. For example, a child may not feel hungry, recognize when they need to pee, or sense when they are getting overstimulated—leading to sudden meltdowns that appear to come “out of nowhere.”

The Subtypes of SPD

SPD presents in diverse ways depending on how the nervous system processes input. Carol Stock Kranowitz and subsequent researchers identify three broad subtypes, each with distinct challenges:

1. Sensory Modulation Disorder (SMD)

Difficulty regulating the intensity of response to sensory input. This includes:

- Over-responsive (hypersensitive): Reacts too strongly to light, sound, textures, or movement (e.g., hates tags, avoids hugs, startles easily)

- Under-responsive (hyposensitive): Doesn’t notice pain, temperature, or motion (e.g., unaware of messy face, doesn’t respond to name)

- Sensory-seeking: Craves intense input (e.g., spins, jumps, crashes, chews objects)

Children may swing between these states depending on context and fatigue levels.

2. Sensory-Based Motor Disorder (SBMD)

Difficulty with movement planning and execution due to poor sensory integration. This includes:

- Dyspraxia: Trouble with motor planning (e.g., difficulty learning to tie shoes, ride a bike, imitate actions)

- Postural Disorder: Poor balance, low muscle tone, and instability (e.g., slouches, tires easily, avoids climbing)

These children may be misjudged as clumsy, lazy, or unmotivated, when in fact their motor systems are overwhelmed or uncoordinated.

3. Sensory Discrimination Disorder (SDD)

Difficulty distinguishing between sensory inputs. These children may:

- Struggle to differentiate similar textures, sounds, or movements

- Misjudge distances or force (e.g., writes too hard, bumps into peers)

- Have difficulty with fine motor tasks like buttoning, handwriting, or catching a ball

Though subtle, SDD can affect academic performance, spatial awareness, and social interaction.

The Complexity—and Beauty—of SPD

No two children with SPD are alike. One may melt down at the smell of glue, another may constantly bump into furniture, and yet another may avoid playgrounds entirely. This complexity can make diagnosis and support difficult—but it also calls for tailored, compassionate care.

SPD is not a single, rigid diagnosis—it is a spectrum of sensory experiences that must be understood through the child’s unique behavior, preferences, and responses.

When adults tune in, the child tunes in. When systems adapt, the child can regulate. When environments honor the child’s needs, their nervous system begins to trust the world—and growth becomes not just possible, but inevitable.

3. Signs and Symptoms Across Ages

Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) does not announce itself with a diagnosis or a single, definitive symptom. It whispers through everyday struggles—an unexpected meltdown in a crowded room, a refusal to wear socks, a child who can’t sit still or one who won’t move at all. These behaviors can be mistaken for moodiness, defiance, or even laziness. But when viewed through the lens of sensory integration, they reveal a deeper truth: the child is not giving us a hard time—they’re having a hard time.

Understanding the age-specific signs and behavioral patterns of SPD helps caregivers and educators know when to observe, when to intervene, and when to simply offer grace.

Sensory-Seeking vs. Sensory-Avoiding Behaviors

At the heart of SPD is a mismatch between sensory input and the brain’s response. Children typically fall into one (or more) of three patterns:

- Sensory-Seeking: These children actively crave intense sensory input. They are often labeled as hyperactive, rough, or impulsive.

Examples: Constant jumping, crashing into walls or furniture, spinning in circles, chewing on sleeves or pencils, making loud vocalizations. - Sensory-Avoiding: These children are hypersensitive to certain stimuli and attempt to control or avoid them. They may be seen as rigid, anxious, or overly emotional.

Examples: Covering ears in response to noise, refusing certain clothing textures, resisting hugs, panicking at grooming activities like haircuts or nail trimming. - Sensory-Inattentive (Under-Responsive): These children may appear spacey, lethargic, or unusually calm because their brain under-registers sensory input.

Examples: Doesn’t react to pain, doesn’t notice name being called, may miss food on their face or not realize they’re sitting uncomfortably.

Importantly, children can exhibit both seeking and avoiding behaviors, depending on the type of input (e.g., a child who avoids bright lights may crave deep pressure through bear hugs).

Typical vs. Atypical Development: When to Worry and When to Adapt

All children have sensory preferences—this is part of typical development. One child loves finger-painting; another detests sticky fingers. A toddler may go through a phase of stripping off clothes, or a kindergartener may temporarily gag at new foods.

SPD becomes a concern when:

- The reactions are extreme, persistent, and out of proportion to the situation

- The sensory challenges interfere with daily functioning—such as eating, sleeping, playing, learning, or connecting with others

- The child shows chronic distress or exhaustion from managing their sensory environment

- The behaviors lead to isolation, rejection, or emotional regression

Parents often ask: Is this just a phase?

A good rule of thumb is: When the child cannot adapt to the world, we must adapt the world to the child—and investigate further.

Red Flags and Real-Life Examples Across Developmental Stages

Infants (0–12 months)

- Red Flags:

- Excessive crying or difficulty soothing

- Dislikes being held or cuddled, or conversely, requires constant movement to stay calm

- Trouble with feeding (difficulty latching, aversion to textures, gags easily)

- Overreacts to noises or visual stimulation

- Delayed motor milestones (e.g., rolling, crawling)

- Example: A 10-month-old cries inconsolably during diaper changes, arches away during cuddling, and startles violently at everyday sounds like the doorbell. The parent feels exhausted and “rejected,” not realizing the infant is battling a hypersensitive tactile and auditory system.

Toddlers and Preschoolers (1–5 years)

- Red Flags:

- Meltdowns in response to routine transitions (e.g., changing clothes, leaving the house)

- Avoids messy play or becomes fixated on spinning, bouncing, or crashing

- Delayed speech or poor articulation not explained by hearing loss

- Picky eating beyond typical toddler pickiness (e.g., rejects entire food categories by texture)

- Doesn’t notice injury or overreacts to minor ones

- Example: A 3-year-old refuses to wear socks, insists on wearing shorts in winter, gags at the smell of peanut butter, and chews on his toys constantly. Teachers report that he can’t sit during circle time and is always “on the go.”

School-Age Children (6–12 years)

- Red Flags:

- Difficulty sitting still, focusing, or copying from the board

- Writes too lightly or too hard, breaks pencils frequently

- Avoids playground activities like swings, slides, or climbing

- Easily distracted by background noise, bright lights, or textures in clothing

- Frequent fatigue, slouching, poor coordination or messy handwriting

- Example: A 7-year-old struggles with reading and avoids P.E. because of poor balance. She is easily overwhelmed by noisy classrooms and often hides under her desk. She’s labeled “shy” or “lazy,” but in truth, her vestibular and proprioceptive systems are dysregulated.

The Emotional and Behavioral Toll of Being Misunderstood

Living with undiagnosed SPD is like navigating the world in a body that doesn’t quite work the way everyone expects—but not knowing why.

The child may be punished for behavior that isn’t willful, leading to:

- Chronic anxiety and self-doubt

- Low self-esteem from repeated failure or rejection

- Emotional outbursts that mask internal chaos

- Social withdrawal due to fear of embarrassment or sensory triggers

The parent, meanwhile, often feels confused, blamed, and isolated. Teachers may mistake the child for a “problem,” further damaging their sense of self.

What’s needed is not more discipline, but more understanding. Not stricter rules, but more compassionate structure. When adults learn to read the child’s behavior as communication—not manipulation, the entire story begins to change.

Final Thought for This Section:

Sensory challenges don’t always look dramatic. Often, they’re subtle—hiding in picky habits, academic struggles, or mysterious fatigue. But when we know what to look for, the signs become invitations to connect, not diagnoses to fear.

These children are not disobedient—they are dysregulated. They don’t need fixing—they need decoding, support, and safety.

4. The Everyday Impact: School, Home, and Social Life

Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) doesn’t only show up in therapy evaluations or clinical descriptions. It reveals itself in the quiet frustration of a teacher, the overwhelmed gaze of a parent, or the confused look of a sibling who just got pushed during play. SPD affects the smallest rituals and the biggest moments in a child’s daily life—sometimes loudly, but often silently.

Let’s explore how SPD affects day-to-day functioning and family systems, and how understanding these impacts can lead to more empowered support rather than constant correction.

Challenges in the Classroom: When Learning Becomes Surviving

School is often the ultimate test of sensory tolerance. A classroom is full of unpredictable noises, shifting routines, group dynamics, and uncomfortable stimuli. For children with SPD, it is not just a place to learn—it is often a place of sensory combat.

Common Struggles:

- Handwriting: Many children with poor proprioceptive input or fine motor delays struggle with pencil grip, pressure control, and spatial awareness. Their letters may be too big, too small, uneven, or shaky. Fatigue is common, and frustration is high.

- Focus and Attention: SPD can mimic or co-occur with ADHD. Children may be unable to filter background noises (e.g., the hum of a projector, chatter from a hallway) or become hyper-focused on sensory distractions like a flickering light or the texture of their chair.

- Noise Sensitivity: Fire alarms, school bells, and even lunchroom noise can trigger panic or shutdown.

- Clothing Discomfort: Uniforms, itchy tags, or tight shoes may create constant physical distress that undermines concentration.

- Transitions: Changing classes, moving from recess to indoor time, or shifting from one activity to another without warning can lead to anxiety, resistance, or outbursts.

The Result:

The child may be labeled disruptive, lazy, avoidant, or inattentive. In truth, they are overwhelmed, and the academic demands become secondary to basic sensory survival.

Sensory Meltdowns vs. Tantrums: Decoding the Behavior

It’s essential to distinguish between a tantrum and a sensory meltdown:

- A tantrum is a willful expression of frustration, usually with an audience and a goal (e.g., wanting a toy, resisting bedtime).

- A sensory meltdown is a loss of emotional control due to sensory overload. It is not manipulative—it is neurological. There is no audience, no desired outcome—just the body’s system shutting down or exploding from the inside.

Key Differences:

Tantrum | Sensory Meltdown | |

Trigger | Emotional (wants something) | Sensory (too much input or discomfort) |

Goal-Oriented? | Yes | No |

Stops When… | The child gets what they want | Only after nervous system resets |

Conscious? | Mostly controlled | Often involuntary or dissociative |

Post-Reaction | May resume activity quickly | Often exhausted, tearful, or withdrawn |

Understanding this difference changes the adult response. Instead of discipline or reasoning, a meltdown requires soothing, safety, and space. Recovery is not a reward—it’s a reset.

Sibling Dynamics, Parental Guilt, and Family Stress

SPD doesn’t just affect the child—it reshapes the entire family ecosystem.

Sibling Impact:

- Siblings may feel jealous of the attention given to the sensory-challenged child.

- They may feel rejected or unsafe during aggressive sensory-seeking behavior (e.g., pushing, crashing, yelling).

- Without explanation, siblings may blame themselves or withdraw.

Parental Guilt and Fatigue:

- Many parents feel like they are “failing” their child or being judged by others.

- They may experience compassion fatigue, mental exhaustion, or even depression from constant battles over basic routines.

- Social isolation is common, especially when family outings or public events result in meltdowns or stares.

Family Stress Points:

- Mealtimes are battlegrounds.

- Getting dressed becomes a 45-minute ordeal.

- Family vacations or weddings may be canceled due to sensory unpredictability.

But when families are given the tools, language, and validation they need, they shift from survival to strategy. They begin to understand that their child’s nervous system is not broken—it simply requires a new way of engaging.

The Subtle Invasion of Daily Routines

SPD infiltrates even the most basic self-care rituals. These are often overlooked or misattributed to “spoiled behavior,” when in fact they are profoundly distressing sensory events.

Sleep:

- Hypersensitive children may struggle to fall asleep due to background noise, temperature, or fabric discomfort.

- Under-responsive children may not register tiredness, leading to bedtime resistance and late-night activity.

- Meltdowns at bedtime often reflect nervous system overload, not just disobedience.

Eating:

- Texture aversions make many foods intolerable.

- Children may gag, vomit, or refuse to eat—even if hungry.

- Smell sensitivity can turn mealtime into a war zone.

- Nutritional deficiencies and social embarrassment (e.g., lunchbox stigma) often follow.

Dressing:

- Tags, seams, tight waistbands, and even socks can cause panic.

- Clothing choices become limited, leading to daily power struggles or refusal to leave the house.

- Uniforms or formalwear for school functions may feel like torture.

Grooming:

- Brushing hair, cutting nails, or dental hygiene can trigger full-scale meltdowns.

- Water (too hot, too cold), soap (too slimy), and touch (too scratchy) can make bath time traumatic.

To the outside world, these may seem like minor irritations. But for a child with SPD, they are moments of real suffering—often endured silently until the emotional dam bursts.

The Ripple Effect: From Misunderstanding to Empowerment

The invisible nature of SPD often creates a painful gap between a child’s internal reality and external expectations. But when caregivers, teachers, and communities understand the sensory lens, everything changes.

- Classrooms become adaptable, not rigid.

- Homes become safe zones, not battlefields.

- Parents become partners, not disciplinarians.

- Siblings become allies, not casualties.

The goal is not to bubble-wrap the child or lower standards. It is to support their nervous system so they can meet the world with more trust, confidence, and calm.

5. Understanding the “Out-of-Sync” Child’s Worldview

“They’re not giving you a hard time. They’re having a hard time.”

— Carol Stock Kranowitz

Sensory Processing Disorder is not a disorder of character or discipline—it is a difference in how a child’s entire nervous system receives and interprets the world. To truly help “out-of-sync” children, we must step out of a lens of control and compliance—and into a lens of curiosity and compassion. This requires not just knowledge, but an emotional shift.

This section attempts to put us in their shoes, so we not only treat behaviors but also honor experience.

Empathy Through Sensory Imagination: What Does It Feel Like?

Imagine starting your day with:

- Socks that feel like sandpaper.

- Lights that pierce like lasers.

- Noises that hit your ears like thunderclaps.

- People touching you without warning.

- Being forced to sit still when your body is begging to move.

For many children with SPD, this is not imagination. It is reality—every single day.

Try this exercise:

- Vestibular Challenge: Spin around ten times quickly and try to read a paragraph aloud while standing still. That dizziness is what some kids feel just walking down a hallway.

- Auditory Overload: Try holding a conversation with someone while a loud radio, vacuum cleaner, and construction drill are playing simultaneously. That’s lunchtime in the cafeteria.

- Tactile Defensiveness: Imagine wearing a wool sweater that itches intolerably—but no one allows you to take it off.

- Proprioceptive Confusion: Try typing while your fingers are slightly numb and you’re not sure how hard you’re pressing. That’s handwriting with poor body awareness.

Empathy arises not when we “tolerate” children’s behaviors but when we understand the lived sensory reality behind those behaviors.

The Mismatch Between Societal Expectations and a Child’s Sensory Needs

Our environments—from schools to public spaces to family routines—are designed around neurotypical norms:

- Sit still.

- Make eye contact.

- Eat what’s on your plate.

- Shake hands.

- Play with others.

- Wear what you’re told.

- Stop making that noise.

These expectations presume a child’s nervous system can regulate input, perform under demand, and self-soothe quickly. Children with SPD often cannot do this, not because they are unwilling—but because they are neurologically unequipped in that moment.

The result? A persistent message of failure.

- “You’re too much.”

- “You’re too loud.”

- “You’re too slow.”

- “You’re too picky.”

- “You’re too sensitive.”

This mismatch leads to chronic emotional fatigue, shame, and self-doubt. Without support, the child may internalize the idea that they are broken, bad, or unworthy. That invisible wound runs deep.

The Invisible Trauma of Sensory Overload

Sensory overload is not merely discomfort. It is a physiological state of threat.

When a child’s sensory system is overwhelmed:

- The amygdala (the brain’s fear center) activates.

- Cortisol (the stress hormone) spikes.

- The prefrontal cortex (logic, speech, memory) shuts down.

They may scream, shut down, run away, or lash out—not from disobedience, but from a primitive survival response. Unfortunately, this is often met with punishment, shame, or exclusion.

Over time, the trauma compounds:

- Hypervigilance develops—they become anxious in anticipation of input.

- Masking increases—they try to “act normal” until they collapse at home.

- Trust erodes—they feel unsafe in places meant to support them.

And yet, this trauma is largely invisible. There are no bruises, no scars. Only a child curled up under a desk, biting their sleeve, misunderstood again.

Strengths of Sensory-Divergent Children: Creativity, Sensitivity, Innovation

Despite (or because of) their sensory differences, many children with SPD demonstrate remarkable abilities:

- Deep Sensitivity: They are finely attuned to people’s emotions, atmospheres, and subtle shifts in tone or energy.

- Inventive Minds: Sensory avoiders often retreat into vivid inner worlds, rich in imagination, stories, and systems.

- Resilient Problem-Solving: Children who live in a world not built for them often learn adaptability and unconventional approaches.

- Tactile & Visual Genius: Some children with tactile or visual sensitivity show excellence in arts, music, design, or spatial reasoning.

- Unique Perspectives: Because they process the world differently, they often ask unusual questions and see connections others miss.

These are not “disabled” children waiting to be fixed. They are divergent learners, feelers, and thinkers needing translation—not transformation.

Toward a Sensory-Informed Society

What if we shifted from:

- “How do we make this child behave?”

to - “What is this child experiencing?”

What if classrooms had quiet corners, texture-free uniforms, and flexible seating?

What if birthday parties included sensory-sensitive spaces?

What if parents had support, not shame, when asking for accommodations?

What if neurodiversity was seen as a design challenge, not a disciplinary failure?

We would begin to unlock the brilliance of children who are not out-of-sync with life—but rather waiting for the world to sync up with their rhythm.

6. Practical Strategies for Parents and Caregivers

“When we tune into the child’s sensory world, we stop reacting and start relating.”

— Inspired by Carol Stock Kranowitz

Raising a sensory-divergent child isn’t about correcting behavior—it’s about co-creating a world that honors their needs. This begins not in therapy rooms, but in living rooms, kitchens, bathrooms, and bedtime routines. You don’t need to be an expert in neuroscience to make an impact—you need to be curious, observant, and willing to try.

This section offers concrete, field-tested strategies that empower parents and caregivers to create environments of regulation, respect, and resilience.

1. Sensory Diets: Daily Nourishment for the Nervous System

A sensory diet is not about food—it is a customized set of activities designed to give a child the sensory input their body craves or lacks. Just as some children need glasses for vision, others need movement, pressure, or quiet to see the world clearly.

Common Sensory Diet Components:

- For Sensory Seekers:

- Jumping on a trampoline

- Crawling through tunnels

- Chewy foods or safe oral-motor toys

- Pushing/pulling weighted items

- For Sensory Avoiders:

- Deep pressure hugs or compression garments

- Dim lighting and noise-canceling headphones

- Slow rocking or swinging

- Tactile bins with preferred textures only

🔶 Tip: Activities must be tailored. What soothes one child may overwhelm another. Work with an OT to build a structured, consistent plan based on observed behaviors.

2. Environmental Modifications: Designing for Sensory Regulation

Children with SPD experience their environment as either a refuge or a trigger. Simple changes to the home can dramatically improve their sense of control and calm.

Sensory-Smart Home Ideas:

- Lighting:

- Use soft, indirect lighting. Avoid flickering fluorescents.

- Introduce warm-toned lamps or natural daylight.

- Textures:

- Allow choice in clothing—remove tags, offer soft materials.

- Provide tactile bins with rice, beans, kinetic sand—for exploration or avoidance.

- Sound:

- Create quiet zones or listening corners with noise-canceling options.

- Use white noise or calming music to buffer ambient chaos.

- Routine:

- Create visual schedules and storyboards.

- Keep daily routines predictable—especially around meals, sleep, and transitions.

🔶 Tip: Let the child help co-design their space. Autonomy breeds regulation.

3. Preparing for Transitions: Predictability and Visual Supports

Transitions—leaving the park, starting homework, going to bed—can trigger meltdowns not from defiance, but from sensory disorientation and emotional anxiety.

Strategies That Work:

- Visual Timers: Show the countdown to the next activity.

- First-Then Boards: “First brush teeth, then story time.”

- Social Stories: Short picture books that explain what’s coming and what’s expected.

- Transition Objects: A favorite item to carry between settings.

- Pre-Event Narration: “In five minutes, we’re putting away toys and heading to dinner. Want to do one last thing?”

🔶 Tip: Transition strategies reduce fear of the unknown—a core anxiety trigger in SPD.

4. Working with Occupational Therapists (OTs): Partners in Progress

Occupational Therapists trained in sensory integration are often the lifeline for parents navigating SPD.

What a Good OT Does:

- Evaluates the child’s sensory profile (seeker, avoider, mixed)

- Designs individualized sensory diets

- Helps develop motor skills and body awareness

- Coaches parents in sensory-informed parenting

Tips for Collaborating with Your OT:

- Keep a sensory journal to track meltdowns, avoidance, triggers.

- Share video recordings of challenging situations.

- Ask for home carryover activities—therapy doesn’t end at the clinic.

- Involve teachers—ask your OT to write a sensory support plan for school.

🔶 Tip: Trust your instincts. If an OT is too rigid or dismisses your observations, seek another opinion. You are the child’s expert-in-residence.

5. Mindful Parenting: Slowing Down, Tuning In, Regulating Yourself First

Children with SPD often co-regulate with the adults around them. If you are anxious, rushed, or emotionally dysregulated, the child’s nervous system mirrors your state.

Foundational Practices:

- Breathe before you respond. Your calm becomes their anchor.

- Validate feelings before correcting behavior. (“That shirt feels awful, huh? Let’s find something softer.”)

- Use descriptive, not judgmental, language. Avoid “bad” or “naughty.”

- Honor pacing. Slow routines down. Rushing = stress.

- Practice radical acceptance. You are not failing. You are learning.

The Deeper Work:

SPD parenting often unearths your own sensory or emotional patterns. Many caregivers discover their own sensory sensitivities or undiagnosed differences. This journey is not just about fixing a child—it is about evolving as a family system.

🔶 Tip: Join support groups, engage in parent coaching, and be kind to yourself. You are doing sacred work.

❤️ In Summary:

- Practical support begins with recognition and readiness—not reprimands.

- A sensory diet, OT collaboration, and mindful caregiving can unlock joy in daily routines.

- Your child’s progress is not linear—but with safe environments and informed parenting, it is transformative.

- You are not alone. SPD parenting requires a village, not just a diagnosis.

7. Classroom Solutions and Teacher Training

“The child who cannot sit still isn’t trying to disrupt the class. They’re trying to regulate their world.”

— Reflecting Kranowitz’s vision of education with empathy

Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) does not stay at home—it follows the child into the classroom, where expectations for uniformity in behavior, posture, attention, and communication often clash with neurological reality. The school environment can become either a launchpad for thriving or a minefield of overwhelm, depending entirely on how educators are equipped.

This section addresses both classroom-level strategies and systemic teacher training essential for inclusive learning.

1. SPD-Aware Teaching Practices: Tools, Not Taboos

Teachers are often undertrained in sensory differences, and yet they hold a crucial key: the ability to reduce overstimulation and offer movement opportunities in neurodivergent-friendly ways. These are not privileges—they are accommodations.

In-Class Support Tools:

- Fidget tools (stress balls, putty, silent twisters) to channel excess energy without distracting others.

- Flexible seating: bean bags, wobble stools, textured chair pads for proprioceptive input.

- Movement breaks: stretch breaks, chair push-ups, “walk and talk” partner discussions every 20–30 minutes.

- Noise management: headphones, quiet corners, carpeted areas, low-noise machines for soothing auditory input.

- Modified lighting: allow natural light, avoid fluorescent flicker, use lamp lighting for quiet zones.

🔶 Tip: Present these tools to the whole class, not just one child. Normalize difference by offering options to all students—this prevents stigma.

2. Universal Design for Learning (UDL): A Framework for Sensory Inclusivity

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a proactive educational approach that recognizes variability in learners—not as an exception, but as a rule. SPD fits beautifully into UDL’s emphasis on multiple means of engagement, expression, and representation.

UDL Applications for Sensory-Diverse Classrooms:

- Provide varied input modes: visual schedules, audio recordings, tactile materials.

- Offer choices in output: oral answers, typed responses, drawing instead of writing.

- Allow self-pacing: extended time, “pause cards” during tests or group work.

- Create sensory-friendly zones: a quiet reading nook, a chill corner, or a standing desk area.

- Embed emotional regulation tools: feelings charts, breathing visuals, mindfulness stations.

🔶 Tip: UDL is not about lowering standards. It’s about flexibility in how we reach them.

3. Communicating with Educators: Empowerment, Not Blame

Parents and teachers often become adversaries when they need to be allies. SPD is invisible, and behaviors may be misread as laziness, manipulation, or oppositional defiance. Clear, respectful communication can build bridges.

How to Advocate Effectively:

- Share a brief sensory profile of your child (PDF or one-pager). Include triggers, calming strategies, and support tools.

- Focus on collaboration, not complaint. (“What’s working at home is this—can we try it here?”)

- Request a meeting with the class teacher, counselor, and special educator—not just email threads.

- Use documentation: OT reports, sensory integration plans, progress logs.

- Show gratitude and patience—it’s a learning curve for the teacher too.

🔶 Tip: Use inclusive language. Avoid clinical jargon. “My child learns better with movement breaks” is more effective than “He has SPD.”

4. Sensory Integration Rooms and Inclusive Pedagogy

In many progressive schools worldwide, sensory integration rooms are becoming as essential as libraries and science labs. These rooms provide safe spaces for sensory exploration, regulation, and calm.

What These Rooms Might Include:

- Swinging equipment, crash pads, body socks

- Bubble lamps, lava lights, tactile walls

- Resistance tunnels, weighted blankets

- Music stations with adjustable volume and frequencies

- Soothing visuals and aromatherapy options

They serve children with diagnosed sensory needs and those struggling with undiagnosed stress, trauma, or anxiety. In India, while such rooms are still rare, a movement toward inclusive infrastructure is emerging—especially in progressive private and NGO-led educational spaces.

Training the Teachers:

- Offer SPD-specific workshops as part of in-service teacher training

- Provide educators with behavior decoding charts: e.g., “Child hides under desk = seeking deep pressure, not avoiding work”

- Encourage co-planning between occupational therapists and special educators for lesson design

- Promote reflective teaching: “How might this activity feel to a child with sound sensitivity?”

🔶 Tip: Teacher empathy rises when training includes simulation exercises—having adults wear headphones, scratchy tags, or experience sensory overload for themselves.

❤️ In Summary:

- A sensory-informed classroom is not a luxury—it is a right for neurodiverse children and a gift for every student.

- UDL provides the framework; SPD-informed tools provide the methods.

- Parents, therapists, and educators form a three-legged stool of support, insight, and consistency.

- Inclusive education is not only about access—it’s about dignity, engagement, and empowerment.

8. Healing, Growth, and Hope

“Children grow when they are seen, heard, and supported—not fixed.”

— Inspired by Kranowitz’s philosophy of possibility

While Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) can present immense daily challenges, it is not a life sentence of struggle. The human brain—especially a child’s brain—is inherently malleable. With timely support, informed interventions, and deep emotional attunement, children with SPD can not only function better but flourish on their own terms.

This section unpacks the science, practices, and mindset shifts that support long-term healing, empowerment, and joy.

1. Neuroplasticity: The Brain’s Hidden Promise

Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s lifelong ability to change, reorganize, and build new connections in response to experience. For children with SPD, this is foundational hope.

How It Works in SPD:

- Repetitive, structured sensory experiences help rewire processing pathways

- Activities targeting vestibular and proprioceptive input improve balance, coordination, and emotional regulation

- Multisensory play can reduce hypersensitivities and support tolerance over time

- The earlier the intervention, the more impactful—but it’s never too late to start

🔶 Realistic insight: While SPD may not “go away,” its impact can be significantly reduced. Skills grow. Adaptations become habits. Struggles shrink.

2. Building Resilience Through Small Wins and Loving Structure

Children with SPD often face a barrage of “no’s,” frustrations, and overwhelm. This can erode self-esteem. Instead of focusing on what they can’t do, we must engineer small, achievable successes that build a sense of agency.

Strategies:

- Break down tasks into manageable steps with visual or sensory cues

- Celebrate tiny victories: brushing teeth without distress, trying a new food texture, sitting through a class circle

- Provide predictable routines—structure is soothing to a dysregulated nervous system

- Use visual calendars, choice boards, and social stories to support autonomy

- Ensure a safe, non-judgmental environment where mistakes are accepted, not punished

🔶 Tip: Every small success changes the child’s story from “I can’t” to “I can—maybe even in my own way.”

3. Fostering Self-Awareness and Self-Regulation

Healing isn’t just about behavior—it’s about helping children understand their own internal states and learn tools to regulate them. This internal empowerment builds lifelong confidence.

Tools for Self-Awareness:

- Feelings thermometers and “zones of regulation” visuals

- Sensory charts (“What helps me feel calm / alert / safe”)

- Mind-body exercises: deep breathing, stretching, tapping, rocking

- Naming and normalizing sensations (“Your body is telling you it needs to move—that’s okay!”)

Long-Term Goal:

To shift from “sensory reactive” to “sensory responsive”—where the child learns to anticipate, adapt, and soothe themselves over time.

🔶 Tip: Co-regulation comes before self-regulation. An adult’s calm presence is the child’s nervous system training ground.

4. The Healing Power of Play, Art, and Movement

Healing for sensory-divergent children does not happen in worksheets and lectures—it happens in the language of the body, through creative and playful expression.

Core Modalities:

- Movement-based therapies: swinging, jumping, climbing, animal walks

- Art therapy: finger painting, clay modeling, scribble drawing—tactile exploration

- Music and rhythm: drumming, humming, dancing—regulates the auditory system

- Dramatic play and storytelling: externalizing internal confusion through roleplay

- Nature-based play: digging, barefoot walking, tree hugging—restores sensory harmony

🔶 Tip: Let the child lead. What looks like “just playing” is often deep regulation work beneath the surface.

5. Celebrating Neurodivergent Gifts: Not Broken, Just Brilliantly Wired

Too often, neurodivergent children grow up hearing what they are not. What if we flipped the script? SPD doesn’t diminish intelligence, creativity, or emotional depth—it just delivers the world through a different channel.

Strengths Common in SPD Children:

- High empathy and emotional sensitivity

- Out-of-the-box thinking and unconventional problem solving

- Deep aesthetic appreciation—sights, sounds, textures others miss

- Hyperfocus and perseverance in areas of passion

- Inventiveness in adapting to sensory discomfort

What these children need is not fixing—they need adults who believe in them, adapt to them, and amplify their gifts.

🔶 Tip: Reframe your language. Instead of “difficult” say “different.” Instead of “resistant,” say “sensitive.” Shift the lens—change the life.

💛 In Summary

- Children with SPD can and do improve—especially when we work with, not against, their sensory reality.

- Healing is not linear, but small daily actions rooted in love, rhythm, and sensory attunement create profound transformation.

- Our job is not to normalize these children, but to normalize inclusion.

- Joy, play, and connection are not luxuries—they are the therapy.

9. Reframing the Narrative: From Disorder to Difference

“What if we stopped asking, ‘What’s wrong with this child?’ and started asking, ‘What does this child need to thrive?’”

— Rooted in the heart of neurodiversity and compassion

The prevailing language around Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD)—with its medicalized tone of deficits and disorders—often obscures a deeper truth: that sensory divergence is not inherently pathological. Instead, it is one of many variations in human experience. By reframing SPD within the neurodiversity paradigm, we move from “fixing the child” to restructuring society to include all kinds of brains and bodies.

This is not just semantic. It’s a paradigm shift that changes everything—from diagnosis to therapy to identity.

1. SPD and the Broader Neurodiversity Movement

The neurodiversity movement, originally championed by autistic self-advocates, holds that neurological differences such as autism, ADHD, SPD, and dyslexia are natural variations of the human genome, not diseases to be cured.

What This Means for SPD:

- SPD is a different way of processing sensory information—not a behavioral problem or cognitive failure

- Interventions should focus on accommodation, empowerment, and communication, not normalization

- Support should evolve from clinical settings to community ecosystems that welcome difference

🔶 Insight: Sensory divergence may feel like dysfunction only because society isn’t designed for it.

2. From Deficit-Based Labels to Strength-Based Support

Traditional language like “impairment,” “maladaptive,” or “disorder” can unintentionally pathologize children who are operating with a different sensory compass. Instead, we need language—and systems—that reflect a more affirming, functional, and inclusive reality.

Practical Applications of Strength-Based Framing:

- Label: “sensory-defensive child” → Reframe: “highly attuned child”

- Label: “problem behavior” → Reframe: “sensory communication”

- Label: “developmental delay” → Reframe: “asynchronous development”

Support Practices:

- Focus on what works for the child, not what is “wrong” with them

- Build on interests, not just deficits

- Provide alternative pathways to success: through art, music, tactile play, or kinesthetic learning

🔶 Tip: When we change our language, we change our expectations—and expectations shape outcomes.

3. Intersection with Autism, ADHD, and Trauma-Informed Care

SPD rarely exists in isolation. It often intersects with, mimics, or accompanies other neurodevelopmental or psychological conditions. Understanding these overlaps helps prevent misdiagnosis and enables integrated care.

Overlapping Diagnoses:

- Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): Many autistic children also experience SPD, but not all children with SPD are autistic.

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Sensory-seeking or avoiding behaviors can resemble hyperactivity or inattention.

- Childhood Trauma/PTSD: Sensory dysregulation is common in trauma survivors; creating safe, predictable environments is essential.

Why This Matters:

- Avoids over-pathologizing and inappropriate medication

- Emphasizes trauma-informed, sensory-safe environments in schools and homes

- Encourages interdisciplinary support teams (OTs, psychologists, special educators)

🔶 Insight: The right question is not “Which label fits?” but “Which support systems free this child to thrive?”

4. Changing Social Narratives and Cultural Stigmas

Much of the distress experienced by out-of-sync children is not from their sensory differences, but from society’s intolerance of those differences.

Current Realities:

- Misunderstood as “naughty,” “lazy,” or “attention-seeking”

- Excluded from classrooms, playdates, and opportunities

- Parents often shamed, isolated, or gaslit by professionals

Shifting the Cultural Narrative:

- Normalize variation: Just as some wear glasses or use ramps, others need sensory headphones or movement breaks

- Celebrate individuality: Value sensitivity, creativity, and emotional depth as assets

- Educate communities: Sensory literacy should be part of parenting, teaching, and public health dialogues

Role of NGOs and Media:

- Advocate for inclusive public spaces—parks, schools, transport

- Amplify voices of neurodivergent individuals in policy and storytelling

- Run community awareness campaigns that make sensory sensitivity visible, not shameful

🔶 Tip: The ultimate measure of an inclusive society is how it treats the children who don’t fit its mold.

💛 Closing Thought

Reframing SPD from disorder to difference is not about denying challenges. It is about choosing dignity over diagnosis, empathy over enforcement, and hope over helplessness. Every child deserves to feel like they belong—not someday, but right now.

10. Systems Thinking: What Society Must Learn and Change

“We don’t need to change the child—we need to change the system.”

Despite growing awareness of Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD), the larger societal structures—education, healthcare, urban design, and policy—remain largely unequipped to support neurodivergent individuals. Without systems thinking, efforts remain fragmented, reactive, and inequitable.

This section calls for a paradigm shift: from isolated interventions to ecosystemic change. SPD is not just a family’s challenge. It is a societal blind spot—one that we can and must correct.

1. The Role of Schools, Medical Systems, and Policy Makers

Education Systems:

- Current Gap: Teachers are often undertrained to recognize sensory needs, leading to misinterpretation as behavioral problems.

- Change Needed:

- Mandatory sensory inclusion training in teacher education programs

- Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) and 504 accommodations that explicitly address sensory issues

- Integration of occupational therapy within school hours, not just as an afterthought

Medical Systems:

- Current Gap: SPD is not recognized as a standalone diagnosis in many diagnostic manuals (e.g., DSM-5), limiting access to services.

- Change Needed:

- Expanded pediatric screening tools for early identification

- Cross-referrals between pediatricians, neurologists, and OTs

- Recognition of SPD within insurance and medical coding systems

Policy Makers:

- Current Gap: Neurodivergent individuals lack representation in policy design.

- Change Needed:

- Policies that mandate sensory audits in schools, parks, public events

- Government support for inclusive infrastructure and therapeutic services

- Data collection on prevalence and outcomes for children with SPD to inform public health strategies

🔶 Insight: Sensory inclusion is a civil rights issue. Inaccessibility is systemic discrimination.

2. The Need for Early Screening in Preschools and Pediatric Clinics

SPD often manifests in early infancy and toddlerhood—long before formal schooling begins. However, it is frequently mistaken for “delayed maturity” or “bad behavior.”

Critical Screening Windows:

- Infancy: Feeding difficulties, hypersensitivity to touch/sound, lack of cuddling response

- Toddlerhood: Extreme aversion to textures, erratic sleep, violent tantrums from overstimulation

- Preschool: Avoidance of messy play, over-reliance on routines, difficulty with transitions

Systemic Recommendations:

- Include sensory checklists during regular pediatric wellness visits

- Train Anganwadi workers, childcare providers, and pre-K teachers to spot early signs

- Fund public health campaigns to educate families across socioeconomic levels

🔶 Early support = faster regulation = fewer secondary issues like anxiety, aggression, or academic delays.

3. Insurance Barriers and Therapy Access

For many families, the diagnosis is just the beginning of an exhausting and expensive journey. SPD-related therapies—especially occupational therapy (OT) and sensory integration therapy—are often:

- Not covered by insurance

- Out of financial reach for low- and middle-income families

- Restricted to urban centers

What Needs to Change:

- Government subsidies and inclusion of SPD under disability benefit schemes

- Therapist training programs in rural and tier-2/3 cities

- Creation of community-based therapy centers tied to public health systems

- Teletherapy platforms with sliding-scale fees for continued access

🔶 Equity in therapy access is not charity—it is a public investment in human potential.

4. Sensory-Friendly Urban Design, Public Spaces, and Events

Our cities and public life are built for neurotypical sensory baselines. For children with SPD, the world can be overwhelming, chaotic, even painful.

Everyday Barriers:

- Loud public announcements

- Fluorescent lighting and echo-heavy rooms

- Scratchy uniforms, crowded public transport, jarring sirens

- Events that overload with noise, smell, light, and social density

Transformational Design Principles:

- Install quiet zones, low-stimulation rooms, or sensory pods in public spaces like airports, malls, and schools

- Ensure adaptive lighting and acoustic controls in classrooms and clinics

- Make sensory-friendly events (quiet hours, reduced lighting/sound, chill-out zones) a norm, not an exception

- Include neurodivergent voices in design review boards and city planning

🔶 Designing for the sensory-sensitive benefits everyone: pregnant women, elders, trauma survivors, introverts, and more.

💡 Systemic Shifts: From Awareness to Transformation

Traditional Approach | Systems Thinking Approach |

Focuses on the child | Focuses on the environment |

Individual therapy | Community adaptation |

Occasional workshops | Policy and institutional reform |

Awareness days | Embedded, permanent practices |

🔔 Final Insight:

To truly support “out-of-sync” children, we must create “in-sync” systems. SPD doesn’t have to remain invisible. With the right changes in schools, cities, policies, and health care, we can build a world that listens to the unheard, sees the unseen, and accepts the unalike.

12. Conclusion: Reclaiming the Sync – A Loving Call to Action

“When a flower doesn’t bloom, you fix the environment in which it grows—not the flower.”

— Alexander Den Heijer

🌍 The World Must Adapt, Not Just the Child

Children with Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) are not broken—they are responding to a world that often overwhelms, misunderstands, and invalidates their sensory truth. The real disorder lies in a society that prizes conformity over compassion, silence over understanding, and convenience over care.

We must evolve from trying to make neurodivergent children fit into rigid systems, to redesigning those systems to welcome diversity of perception and experience. This isn’t just an SPD issue—it’s a human rights imperative.

🤝 Compassion, Awareness, and Collective Wisdom Can Make a Profound Difference

Progress is not driven by experts alone. It happens when:

- A parent holds space for a meltdown without shame

- A teacher retools the classroom for sensory comfort

- A neighbor quiets the noise out of love

- A society normalizes difference without pathologizing it

Every act of kindness rooted in understanding changes the narrative from “what’s wrong with this child?” to “what does this child need to thrive?”

💖 Every Child Deserves to Feel Safe in Their Body and at Home in the World

The sensory world of a child is not visible to the naked eye. But it is very real. When we dismiss their discomfort, we erode trust. When we believe them, we become bridges.

Let us become advocates, not fixers. Listeners, not silencers. Mirrors, not molds. When children feel safe in their bodies, they learn. When they feel seen, they grow. When they are embraced as they are, they shine.

🎵 Let’s Lead with Love, Not Fear—and Help Every Child Find Their Rhythm

In every child who struggles to sit still, there’s a soul craving movement. In every child who screams at the seams of sensory chaos, there is a signal—not defiance, not dysfunction, but distress.

Let us be the generation that chose to tune in rather than shut down. That chose to dance to each child’s rhythm, no matter how unusual the beat.

Because in that dance, we do not just rescue a child from isolation.

We reclaim our own humanity.

📚 Book References and Further Reading

To deepen your understanding, we highly recommend these seminal works:

- Carol Stock Kranowitz – The Out-of-Sync Child

- Carol Stock Kranowitz – The Out-of-Sync Child Has Fun

- Jean Ayres – Sensory Integration and the Child

- Lindsey Biel & Nancy Peske – Raising a Sensory Smart Child

- Temple Grandin – The Autistic Brain

- Mona Delahooke – Beyond Behaviors

- Stephen Porges – The Polyvagal Theory

Each book offers deep insights into the neurological, emotional, and practical dimensions of SPD, empowering caregivers and communities with actionable tools and heartfelt wisdom.

🌱 Participate and Donate to MEDA Foundation: Co-Creating a Sensory-Inclusive World

At MEDA Foundation, we believe that every child—regardless of their neurological wiring—deserves the right to learn, play, work, and live with dignity.

Your support can:

- Help us train parents and teachers across India in sensory literacy

- Build sensory-friendly learning and therapeutic spaces

- Sponsor occupational therapy access for underserved families

- Launch awareness drives in schools, pediatric centers, and urban communities

🙏 You can be the difference. Whether through time, funds, resources, or word-of-mouth, every action ripples outward.

➤ Visit: www.MEDA.Foundation

➤ Donate | Volunteer | Partner | Advocate

💬 Final Thought:

SPD is not a flaw to be corrected—it is a language to be understood. When we learn that language, we don’t just help children regulate their senses.

We help them sense that they belong.