India’s education system, dominated by marks, ranks, and rote memorization, has created a generation of learners who fear failure and value compliance over understanding. Real reform requires shifting focus from memory to reasoning, cultivating curiosity, and embracing pedagogical models that prioritize thinking, questioning, and application. By redefining assessments, empowering teachers as mentors, engaging parents, leveraging boards like NIOS, and building supportive learning ecosystems, it is possible to break systemic fear, honor individual potential, and create inclusive, future-ready learners capable of solving real-world problems while retaining the dignity of learning.

ಭಾರತದ ಶಿಕ್ಷಣ ವ್ಯವಸ್ಥೆ, ಅಂಕಗಳು, ಶ್ರೇಣಿಗಳು ಮತ್ತು ಮೆಮೊರೈಜೆಶನ್ಗೇ ಆಧಾರಿತವಾಗಿದೆ, ಇದು ಸೋಲು ಭಯದಿಂದ ಗಿರಿಳುವ ಮತ್ತು ಬುದ್ಧಿವಂತಿಕೆಯನ್ನು ಬದಲಾಗಿ ಅನುಸರಣೆಗೇ ಮೌಲ್ಯ ನೀಡುವ ವಿದ್ಯಾರ್ಥಿಗಳ ಪೀಳಿಗೆ ನಿರ್ಮಿಸಿದೆ. ನಿಜವಾದ ಸುಧಾರಣೆ ಅರ್ಥಪೂರ್ಣವಾದ ಕಲಿಕೆಗೆ ಗಮನಸೆಳೆಯುವ ಮೂಲಕ, ಕುತೂಹಲವನ್ನು ಬೆಳೆಸುವ ಮೂಲಕ ಮತ್ತು ವಿಚಾರ, ಪ್ರಶ್ನೆ ಮತ್ತು ಅನ್ವಯವನ್ನು ಆದ್ಯತೆ ನೀಡುವ ಪಾಠಶೈಲಿ ಮಾದರಿಗಳನ್ನು ಅಳವಡಿಸುವ ಮೂಲಕ ಸಾಧ್ಯ. ಮೌಲ್ಯಮಾಪನವನ್ನು ಪುನರ್ವ್ಯಾಖ್ಯಾನಿಸುವುದು, ಶಿಕ್ಷಕರನ್ನು ಗುರುಗಳಾಗಿ ಶಕ್ತಿಪೂರಕಗೊಳಿಸುವುದು, ಪೋಷಕರನ್ನು ತೊಡಗಿಸುವುದು, NIOS ಮೊದಲಾದ ಮಂಡಳಿಗಳನ್ನು ಸಮರ್ಥವಾಗಿ ಬಳಸುವುದು ಮತ್ತು ಬೆಂಬಲಿತ ಕಲಿಕಾ ಪರಿಸರಗಳನ್ನು ನಿರ್ಮಿಸುವ ಮೂಲಕ, ವೈಯಕ್ತಿಕ ಸಾಮರ್ಥ್ಯಕ್ಕೆ ಗೌರವ ಸಲ್ಲಿಸುವ, ಭವಿಷ್ಯಕ್ಕೆ ತಯಾರಾದ, ವಾಸ್ತವಿಕ ಸಮಸ್ಯೆಗಳನ್ನು ಪರಿಹರಿಸಲು ಸಮರ್ಥ ವಿದ್ಯಾರ್ಥಿಗಳನ್ನು ರೂಪಿಸಬಹುದು ಮತ್ತು ಕಲಿಕೆಯ ಗೌರವವನ್ನು ಉಳಿಸಬಹುದು.

From Rote to Reason: Reclaiming Education as the Art of Understanding

Education Reform Is Not Optional—It Is Civilizational

India cannot reform education superficially and expect transformational outcomes. Rote learning is not a flaw in the system; it is the logical output of a system designed for ranking, compliance, and control. Real reform demands that we dismantle the obsession with marks, democratize dignity across school types, and reposition education as the cultivation of thinking, judgment, and humane intelligence.

This article argues that learning by understanding is not a pedagogical luxury—it is a national survival skill in an age where memory is automated and relevance is fleeting.

To understand why this moment is civilizational rather than merely administrative, we must first look backward—not nostalgically, but honestly—at how India once understood education.

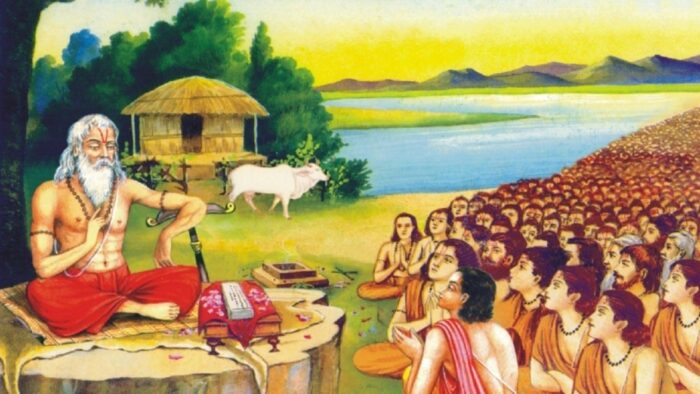

In the Gurukula system, education was not a service delivered, a syllabus completed, or a certificate earned. It was a way of being shaped. The student (śiṣya) did not enter an institution; he or she entered a relationship—with the guru, with nature, with discipline, and with truth. Learning unfolded through śravaṇa (listening), manana (contemplation), and nididhyāsana (deep internalization). Knowledge was not transferred; it was realized.

Crucially, the Gurukula system never separated knowing from living. Arithmetic was learned through trade and measurement. Astronomy through observation of the sky. Ethics through daily conduct. Philosophy through dialogue and silence. Education was slow by design, contextual by necessity, and personal by intent. There were no ranks because there was no race; no marks because learning was evident in action and character; no standardized outcomes because human beings were not standardized inputs.

Contrast this with the modern system we have inherited and amplified. Today’s education architecture treats students as batches, teachers as delivery mechanisms, and learning as a measurable commodity. The dominance of marks, ranks, and certificates is not accidental—it mirrors the logic of industrial production, colonial administration, and bureaucratic convenience. The system does not ask, “Has the student understood?” It asks, “Can the student be compared?”

This is where the civilizational fracture lies.

Ancient Indian education was purpose-driven. Modern education is filter-driven. One sought to awaken buddhi (discernment); the other optimizes for recall under pressure. One prepared individuals for dharma—right action in the world; the other prepares them for placement statistics. The tragedy is not that students memorize; the tragedy is that they are never taught why they are learning in the first place.

The Gurukula system understood something modern neuroscience is rediscovering: understanding precedes retention, not the other way around. A concept grasped deeply stays effortlessly; a fact memorized without meaning evaporates under stress. Yet our current system reverses this order, forcing memory first and hoping understanding will follow—if time permits. It rarely does.

Even more dangerously, rote learning reshapes aspiration itself. When education rewards repetition, students stop aspiring to wisdom and start aspiring to scores. Curiosity becomes risky. Questioning becomes inefficient. Silence becomes safer than thinking aloud. Over time, this does not just produce poorly educated citizens; it produces inwardly dependent minds—waiting for instructions, approvals, and validations.

From a civilizational standpoint, this is untenable.

India today stands at a paradoxical crossroads. We invoke ancient wisdom in speeches while running classrooms on fear and fragmentation. We speak of innovation while punishing intellectual risk. We celebrate heritage while structuring education in ways fundamentally hostile to how that heritage understood learning.

Reform, therefore, cannot mean cosmetic changes—new policies, new acronyms, new boards. It requires a return to first principles, not old forms. The Gurukula was not great because it was ancient; it was great because it was aligned with human nature. Any modern reform that ignores this alignment—how humans actually learn, internalize, and mature—will only reproduce rote learning in more sophisticated disguises.

Learning by understanding is not about abandoning rigor. On the contrary, it demands more rigor—intellectual, ethical, and emotional. It asks harder questions:

- Can the learner explain this in their own words?

- Can they apply it in a new context?

- Can they live it, not just repeat it?

In an age where artificial intelligence can outperform humans in memory, calculation, and pattern recognition, the only defensible role of human education is the cultivation of judgment, values, synthesis, and wisdom—precisely the domains the Gurukula system prioritized.

To ignore this is not merely an educational failure. It is a civilizational abdication.

![]()

Why This Article Matters Now (Context & Crisis)

- The Rote Learning Trap Is Systemic, Not Cultural

It is convenient—and intellectually lazy—to blame India’s rote learning problem on culture. The truth is more uncomfortable: rote learning is not a cultural flaw; it is a systemic outcome. When education systems are designed to rank, sort, and control large populations efficiently, rote learning emerges naturally, almost inevitably.

Paulo Freire called this the “banking model” of education—a system where students are treated as empty vessels and teachers as depositors of information. In such a model, questioning is dangerous, dialogue is inefficient, and obedience becomes the hidden curriculum. Learning is reduced to accumulation, not transformation.

John Holt went further by observing classrooms closely and compassionately. His insight was devastatingly simple: children do not fail because they are incapable; they fail because they are afraid. Fear of exams. Fear of judgment. Fear of being wrong. Under constant evaluation pressure, curiosity withers. The mind stops exploring and starts defending.

India’s exam culture has perfected this trap at scale. High-stakes testing, relentless comparisons, and early labeling of “merit” versus “failure” have turned learning into a survival exercise. Students learn not to understand, but to avoid punishment and secure approval.

From the lens of ancient Indian pedagogy, this is a grave distortion. The Gurukula system assumed that learning unfolds naturally when fear is absent and meaning is present. The modern system assumes the opposite—that fear motivates learning. History, neuroscience, and lived experience all suggest otherwise.

Key Insight:

Rote learning persists not because Indians lack creativity or curiosity, but because rote learning produces what the system rewards—obedience, predictability, and fast sorting, not understanding.

- Marks, Ranks, and Certificates Have Replaced Meaning

At the heart of the modern education crisis lies a dangerous illusion: the belief in the “average student.” Todd Rose, in The End of Average, dismantles this myth with scientific precision. There is no normal learner—only statistical abstractions created for administrative convenience.

India’s obsession with percentiles, cut-offs, and ranks assumes that intelligence can be plotted neatly on a single scale. This assumption is not just wrong; it is harmful. It flattens the rich diversity of human cognition into narrow numerical outcomes and then treats those numbers as destiny.

In ancient India, learners were never compared en masse. The guru observed the svabhāva (natural disposition) of each śiṣya and guided learning accordingly. Some were contemplative, some practical, some artistic, some analytical. Education adapted to the learner—not the other way around.

Modern standardization reverses this wisdom. Neurodiverse learners, creative thinkers, late bloomers, hands-on problem solvers, and emotionally intelligent students are systematically sidelined—not because they lack ability, but because they do not fit the template. Certificates replace competence. Marks replace meaning.

What emerges is a generation trained to ask, “Will this be in the exam?” instead of “Why does this matter?” When meaning disappears, motivation collapses—and anxiety takes its place.

Hard Truth:

Standardization was built for factories and bureaucracies, not for nurturing human potential or wisdom.

- Stratified Schooling Is Policy-Enabled Inequality

Ivan Illich warned decades ago that institutionalized schooling often reproduces social hierarchy while pretending to offer mobility. Education becomes a ritual of legitimacy rather than a pathway to liberation. India’s present schooling ecosystem validates this warning with painful clarity.

Differential funding and branding—KPS schools, PM SHREE schools, Morarji Desai schools, aided schools, private boards, elite boards—have quietly created educational caste systems. Each tier carries not just different resources, but different expectations, confidence levels, and life trajectories.

This stratification contradicts the philosophical foundations of Indian thought. The Gurukula did not ask where a student came from; it asked who the student could become. Learning spaces were austere but dignified, disciplined but humane. Equality was not declared; it was practiced through shared living, shared labor, and shared inquiry.

Today, boards like CBSE dominate not because of superior pedagogy, but because of signaling power. NIOS, despite its learner-centric flexibility and alignment with lifelong learning, suffers from a perception problem rather than a purpose problem. The system teaches society—implicitly but powerfully—that some learners deserve better structures than others.

This is not accidental. It is policy-enabled.

Blunt Reality:

You cannot preach equality of thought, innovation, and democracy while designing inequality of opportunity into the education system itself.

What Must Change: Core Shifts Required for Learning by Understanding

- Redefining the Purpose of Education

At the heart of meaningful reform lies a deceptively simple but profoundly disruptive question: What is education for?

Until this question is answered honestly, all reforms will remain cosmetic.

Modern schooling has quietly reduced education to content delivery—a transactional process where predefined information is transferred from syllabus to student, verified through examinations, and certified through marks. This model treats knowledge as a static commodity and the learner as a passive recipient. Paulo Freire warned that such an approach does not liberate minds; it conditions them. It produces compliance, not consciousness.

Freire’s call was radical yet humane: education must become a practice of freedom, not an act of domination. Learning, in his view, was not about absorbing facts but about developing the capacity to read the world, question power, and act with awareness. Education, therefore, was never neutral—it either humanizes or dehumanizes.

Seymour Papert approached the same truth from a different direction. Drawing from cognitive science and lived experimentation, he showed that children learn best when they actively construct knowledge—by building models, testing ideas, making mistakes, and explaining their reasoning. Learning deepens when the learner becomes a creator, not a consumer. Understanding emerges through interaction, not instruction alone.

This insight resonates deeply with the ancient Indian approach to learning. In the Gurukula, students did not memorize philosophy; they lived philosophical inquiry. They did not study ethics as a subject; they practiced it through daily conduct. Knowledge was forged through dialogue (samvāda), experimentation (prayoga), and reflection (chintana). The learner was expected to wrestle with ideas, not recite them.

To redefine the purpose of education today is to reclaim this orientation. Education must move from:

- Producing exam-ready candidates

to - Cultivating aware, capable, and responsible human beings.

This shift demands that we stop asking only, “What should students remember?”—a question suited to an age of scarcity of information. Instead, we must ask, “How do students think, question, connect, and create?”—a question suited to an age of overwhelming information and rapid change.

When education focuses on understanding, several transformations follow naturally:

- Questions become more valuable than answers.

- Mistakes become data, not disgrace.

- Dialogue replaces monologue.

- Learning becomes intrinsically motivated rather than fear-driven.

Such an education prepares learners not just for jobs, but for life in uncertainty—for ethical decision-making, civic participation, and personal responsibility. It produces citizens who can interpret complexity rather than memorize instructions.

Until we redefine the purpose of education from content delivery to consciousness development, every syllabus reform, policy announcement, or board restructuring will merely rearrange the furniture inside a collapsing house.

True reform begins not with what we teach, but with why we teach at all.

- Reimagining Assessment Without Abandoning Rigor

One of the most persistent myths in education reform is that moving away from rote memorization inevitably lowers standards. This belief has survived not because it is true, but because it is convenient. John Holt and Todd Rose, from different vantage points, expose the same fallacy: rigor is not the enemy of understanding—misplaced rigor is.

John Holt observed that high-stakes testing does not measure learning; it measures fear management under artificial constraints. Children learn quickly what is rewarded: speed over depth, certainty over curiosity, and silence over exploration. Over time, they stop thinking aloud and start guessing what the examiner wants. What appears as “achievement” is often strategic compliance.

Todd Rose adds a structural critique. When assessment is standardized for an imaginary “average student,” it inevitably misrepresents real learners. Some think slowly but deeply. Others reason visually, spatially, or narratively. Many require context before abstraction. A single timed test flattens this diversity and then mistakes the flattening for fairness.

Ancient Indian education understood assessment very differently. Learning was evaluated continuously through dialogue, demonstration, and application. A student’s grasp of grammar was evident in speech, of mathematics in measurement and trade, of philosophy in argumentation and conduct. There were no final exams because learning was always visible.

Reimagining assessment today does not mean abandoning rigor; it means restoring intellectual honesty. Rigor must test:

- Depth of understanding

- Ability to transfer concepts across contexts

- Quality of reasoning and judgment

- Capacity to explain, defend, and revise ideas

This demands a diversified assessment ecology, including:

- Open-book examinations that test synthesis rather than recall

- Concept maps that reveal how learners organize and connect ideas

- Oral reasoning and viva-style evaluations that expose clarity of thought

- Project defenses where students must justify decisions and trade-offs

- Learning portfolios that track growth over time, not performance on a single day

Such methods are harder to design and evaluate—but they are also harder to fake. They reward understanding, not memorization strategies.

The uncomfortable question must be asked openly:

If Google remembers better than humans, why are we still testing memory?

In an age of ubiquitous information, assessing recall is not just obsolete—it is irresponsible. Education must test what machines cannot easily replicate: meaning-making, ethical judgment, creativity, and contextual intelligence.

- Repositioning NIOS as a Future-Ready Board

Among India’s most underutilized educational assets is the National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS). Its marginalization is not due to weak pedagogy, but to misaligned narratives and inherited prejudices. Ivan Illich’s critique of institutional schooling helps us see why.

Illich argued that schooling often confuses attendance with learning and certification with competence. Open systems that break this monopoly are seen as inferior because they threaten institutional control. NIOS, by design, disrupts the notion that learning must occur at a fixed pace, in a fixed place, for a fixed kind of learner.

From a Papert-inspired perspective, NIOS is not a compromise—it is a prototype of future education. It aligns naturally with:

- Self-paced learning, respecting individual cognitive rhythms

- Modular credentials, allowing learners to build competence step by step

- Skill-linked education, connecting knowledge to real-world application

These features mirror the Gurukula ethos more closely than any rigid board structure. Learning was never time-bound or age-segregated; progress was determined by readiness, not calendars.

Yet today, NIOS is framed socially as a board for those who “could not cope.” This framing is both inaccurate and unjust. In reality, NIOS is ideally suited for:

- Innovators and early entrepreneurs

- Neurodiverse learners who do not thrive under standardized pacing

- Athletes, artists, and caregivers balancing multiple responsibilities

- Lifelong learners seeking reskilling in a changing economy

What is required is a narrative correction, not merely administrative support.

NIOS must be publicly repositioned as:

- A board of learning freedom, not academic failure

- A legitimate pathway for serious, self-directed learners

- A bridge between education, skills, and dignified work

The deeper truth is this: the future of education will look far more like NIOS than like traditional boards. Flexible, modular, learner-centric systems are not deviations—they are inevitabilities.

Narrative Correction:

NIOS is not an alternative for dropouts; it is an alternative to outdated schooling models that confuse rigidity with rigor.

How Reform Can Begin Despite the Nexus

The greatest obstacle to education reform in India is not a lack of ideas, evidence, or intent—it is the nexus of inertia. Boards, funding structures, examination bodies, coaching industries, political optics, and parental anxieties form a self-reinforcing loop. Expecting this system to reform itself from the center is unrealistic.

History offers a different lesson: every meaningful education reform began at the margins, not at the ministry.

- Reform Through Islands of Excellence

Seymour Papert’s work in constructionism makes one principle unmistakably clear: real learning emerges in environments where experimentation is permitted and failure is safe. Such environments rarely arise through large-scale mandates; they emerge through carefully protected pockets of practice.

System-wide reform will inevitably face resistance—bureaucratic, cultural, and economic. The solution is not confrontation but demonstration.

Reform must begin through islands of excellence:

- Concept-first classrooms, where depth is valued over coverage

- Project-led syllabi, anchored in real-world problems and interdisciplinary thinking

- Teacher-as-mentor models, where guidance replaces instruction and dialogue replaces dictation

These pilots do not require permission from the entire system. They require conviction, documentation, and continuity. When learners from such environments demonstrate stronger reasoning, adaptability, and confidence, the results speak louder than policy papers.

Ancient Gurukulas functioned precisely in this way. They were not mass institutions but centers of excellence, each shaped by the strengths of the guru and the needs of the learners. Their influence spread not through uniformity, but through reputation and replication.

The critical next step is horizontal scaling—sharing practices across schools, teacher communities, NGOs, and alternative boards rather than attempting top-down enforcement. Proof of concept must precede scale.

Historical Pattern:

Every meaningful education reform—from the Gurukula to the Montessori classroom to modern project-based learning—began at the margins and moved inward.

- Teacher Transformation Is the Keystone

No education system can rise above the quality of its teachers—but it can easily suffocate them.

Paulo Freire and John Holt both recognized a painful truth: teachers are often agents of a system they did not design and do not control. They are evaluated on syllabus completion, exam results, and classroom order—not on intellectual growth or learner confidence. Innovation becomes professionally risky; compliance becomes safe.

Teachers are not the problem. They are trapped inside broken incentives.

Reform demands a fundamental redefinition of the teacher’s role—from content transmitter to architect of thinking environments. This requires retraining teachers to:

- Ask better, deeper, and more open-ended questions

- Facilitate dialogue rather than dominate it

- Diagnose thinking errors instead of merely correcting answers

- Encourage intellectual risk-taking without fear of ridicule or penalty

In the Gurukula tradition, the guru was not a lecturer but a companion in inquiry. Authority came not from control, but from lived wisdom and ethical example. Teaching was relational, not procedural.

Modern teachers must be liberated to reclaim this role. This means:

- Reducing administrative overload

- Valuing pedagogical experimentation

- Creating communities of practice rather than inspection regimes

When teachers feel safe to think, students feel safe to learn.

Core Belief:

Empowered teachers do not produce obedient students; they produce liberated learners.

- Parents Must Be Re-Educated First

Perhaps the most sensitive—and most neglected—dimension of reform is the role of parents. John Holt observed that much of children’s anxiety originates not in classrooms, but in adult expectations. Todd Rose explains why: parents equate standardization with safety because the system trained them to do so.

For decades, marks, ranks, and brand-name boards have been sold as insurance policies against an uncertain future. Parents are not irrational; they are responding to a system that punished deviation. However, this fear-driven logic now actively harms learning and mental health.

Reform cannot succeed unless parents are engaged as partners in understanding, not consumers of credentials.

This requires deliberate efforts in:

- Parent literacy on learning science—how children actually learn, forget, and grow

- Exposure to long-term outcomes, not just immediate scores

- Honest conversations about anxiety, burnout, and relevance in a changing world

Ancient Indian education placed responsibility on the entire community. Parents chose gurus not for prestige, but for character and wisdom. Education was entrusted, not outsourced.

Today’s parents must be gently but firmly confronted with an uncomfortable truth: chasing marks may deliver short-term success at the cost of long-term resilience.

Uncomfortable Truth:

Many parents say they want learning, but behave as if they only want success—until success collapses under its own pressure.

The Role of Civil Society and MEDA Foundation

- Education Reform Needs Ecosystems, Not Policies Alone

Education reform in India has never failed due to a lack of policy. It has failed because policy alone cannot change lived reality. Ivan Illich warned that large institutions, even with noble intentions, tend to preserve themselves before they serve people. When education is treated as a centralized service rather than a living ecosystem, reform becomes slow, diluted, and performative.

What India needs now is not another circular or framework, but parallel ecosystems of learning—spaces where understanding, dignity, and usefulness are restored together.

This is where civil society becomes indispensable.

Illich envisioned “learning networks” that operate beyond formal classrooms—flexible, voluntary, peer-driven, and rooted in real-world relevance. Ancient India practiced precisely this. Learning was not confined to buildings; it happened in forests, workshops, farms, courts, and households. Knowledge flowed through relationships and purpose, not timetables.

MEDA Foundation’s mission aligns naturally with this civilizational logic.

MEDA’s work demonstrates that education cannot be isolated from life. It must be embedded in livelihood, community, and self-worth. By focusing on learning beyond classrooms, MEDA restores context to education. By building skill-to-employment pathways, it re-establishes the dignity of work. By prioritizing neurodiverse inclusion, it challenges the dangerous myth that intelligence comes in only one acceptable form. By nurturing self-sustaining community ecosystems, it moves beyond charity into capacity-building.

These are not peripheral activities; they are models of the future.

Non-governmental organizations have three strategic advantages that formal systems lack:

- They can move faster without waiting for universal consensus.

- They can experiment ethically, learning from failure without fear of reputational collapse.

- They can humanize reform, keeping learners visible rather than abstract.

In the Gurukula system, education thrived because it was relational, contextual, and purpose-driven. Civil society organizations like MEDA recreate these conditions in modern forms—bridging ancient wisdom with contemporary realities.

The strategic opportunity is clear. While the formal system debates reforms, civil society can prototype what works, generate evidence from the ground, and demonstrate scalable alternatives. Over time, these living examples exert moral and practical pressure on the system to adapt.

Education reform will not arrive as a grand announcement. It will emerge through hundreds of quiet successes, patiently built and openly shared.

Strategic Opportunity:

Civil society can prototype the future of education while the system catches up—and MEDA Foundation stands as a credible, compassionate, and courageous example of how this can be done.

Why Rural Schools Are Actually Better Positioned Than Urban Ones

A rural school does not need expensive infrastructure, smart boards, or policy permissions to break free from rote learning. What it needs is courage to change classroom behavior, clarity about purpose, and consistency in small daily practices. Rote learning survives not because of poverty, but because of habit, fear, and imitation of urban exam culture. A rural school can dismantle it—starting tomorrow.

Below is a practical, India-grounded, low-cost, high-impact roadmap, rooted in Gurukula principles and modern learning science.

Before solutions, an important reframing:

- Rural schools are closer to life, work, nature, and community.

- They are not yet fully captured by coaching mafias and brand anxiety.

- Children already learn through observation, doing, and imitation at home.

Irony: Urban schools need to recreate experiential learning. Rural schools already live inside it.

What a Rural School Can Do — Immediately and Practically

- Change the Question Culture (Zero Cost, Immediate Impact)

Stop asking:

- “What is the answer?”

- “Who remembers?”

Start asking:

- “Why do you think this happens?”

- “How do you know?”

- “Can you explain it in your own words?”

- “Where do we see this in our village?”

This single shift:

- Breaks memorization habits

- Forces thinking

- Signals that understanding matters more than speed

Gurukula parallel: Samvāda (dialogue), not recitation.

- Teach One Concept Slowly Instead of Ten Chapters Fast

Practical rule:

One deeply understood idea per week is better than ten memorized ones per day.

Example:

- Teach fractions using land division, ration sharing, crop yields.

- Teach science through wells, soil, seasons, cattle, cooking.

- Teach economics through local markets, self-help groups, farm loans.

Depth creates confidence. Confidence kills rote learning.

- Make Students Explain Before Writing

Before any written test or homework:

- Ask students to say the answer aloud in their own language.

- Let peers ask questions.

- Only then allow writing.

This:

- Exposes fake learning immediately

- Builds language, logic, and courage

- Reduces copying and fear

Rule: If a child cannot explain it, they do not understand it—no matter what is written.

- Replace “Note Writing” with “Note Making”

Instead of dictating notes:

- Ask students to write:

- What they understood

- One question they still have

- One real-life example

Even poorly written thoughts are better than perfectly copied nonsense.

Teacher mindset shift:

Messy thinking is progress. Neat notebooks can be deception.

- Use Local Work as Curriculum (No Textbook Required)

Turn village life into the syllabus:

Subject | Village Context |

Math | Measurements, wages, interest, yield |

Science | Water cycles, seeds, animals, tools |

Language | Storytelling, letters, interviews |

Social Studies | Panchayat, festivals, migration |

Gurukula truth: Knowledge was always connected to karma (action).

- Make Projects, Not Just Exams

Once every month:

- One group project

- Oral presentation

- No memorization allowed

Examples:

- Why crops fail

- How water reaches our village

- How prices are decided in markets

- What skills bring income here

Projects teach:

- Thinking

- Cooperation

- Responsibility

- Pride in local knowledge

- Reduce Fear Before You Reduce Syllabus

Rote learning is fear-based.

So schools must actively remove fear:

- No public shaming

- No punishment for wrong answers

- Praise effort, not just correctness

- Let students say “I don’t know” safely

Hard truth: A scared child cannot think.

The Teacher Is the Lever — Not the Building

- Retrain Teachers in Questioning, Not Content

Teachers already know the syllabus.

What they need is training in:

- Asking open-ended questions

- Listening without interrupting

- Allowing silence

- Letting students struggle productively

Even one trained teacher can change an entire school’s culture.

Parents Must Be Handled Wisely (Especially in Rural India)

- Talk to Parents in Simple, Honest Language

Parents fear that:

- “My child will fall behind”

- “Marks mean safety”

Tell them:

- Understanding improves marks later

- Fear reduces learning immediately

- Skills matter more than certificates

Show them:

- Children explaining concepts aloud

- Practical work

- Confidence growth

Seeing beats convincing.

What Not to Do (Common Mistakes)

- Do NOT copy urban “smart school” models blindly

- Do NOT overload teachers with paperwork

- Do NOT abolish exams suddenly

- Do NOT shame rote learners — they are victims, not culprits

The Bigger Picture — Why This Matters

Rural India does not need exam factories.

It needs thinking citizens, skilled hands, and confident minds.

If rural schools break free from rote learning:

- Migration becomes a choice, not compulsion

- Youth create local value

- Education regains dignity

This is where MEDA Foundation’s mission aligns deeply:

- Learning linked to livelihood

- Neurodiverse inclusion

- Self-sustaining ecosystems

1-Year Action Plan for a Rural School to Move from Rote to Understanding

WHY THIS PLAN WORKS (Before the How)

- It does not require new infrastructure

- It does not violate board rules

- It works inside existing syllabus and exams

- It changes behavior first, not paperwork

- It is rooted in Gurukula principles: dialogue, observation, practice, mentorship

PHASE 1: FOUNDATION & MINDSET RESET (Months 1–3)

Goal:

Break fear, reset expectations, and prepare teachers and parents for change.

- Teacher Orientation (Month 1)

Objective: Shift teachers from “coverage” to “understanding”.

Actions:

- 2 half-day internal workshops:

- Workshop 1: Why rote learning exists (fear, exams, habit)

- Workshop 2: How children actually learn (examples, errors, dialogue)

Key practices introduced:

- Ask why/how questions daily

- Allow “wrong answers” without punishment

- Replace dictation with discussion at least once per day

Success marker:

Teachers consciously pause before giving answers.

- Classroom Behavior Rules Reset (Month 1–2)

Introduce 5 school-wide learning rules:

- No laughing at wrong answers

- “I don’t know” is acceptable

- Every answer must have a reason

- Local examples are welcome

- Silence is thinking time, not failure

Display these in every classroom.

Gurukula parallel: Learning without fear (abhaya).

- Parent Alignment Meetings (Month 2–3)

Objective: Reduce resistance before it builds.

Actions:

- One group meeting per grade cluster

- Simple language, no jargon

Messages to parents:

- Understanding improves marks over time

- Fear reduces learning immediately

- We are not removing exams—only improving thinking

Demonstration:

- Ask children to explain one concept aloud

Success marker:

Parents begin asking how children are learning, not just marks.

PHASE 2: CLASSROOM PRACTICE TRANSFORMATION (Months 4–6)

Goal:

Change daily teaching habits without changing syllabus.

- Concept-First Teaching (All Subjects)

Rule:

One key idea per week, deeply taught.

Examples:

- Math: Fractions via land division, grain sharing

- Science: Evaporation via drying clothes

- Social Studies: Panchayat through observation

- Language: Storytelling before grammar

Teachers must answer:

- What is the core idea this week?

- Where does the child see this in real life?

- Oral Explanation Before Writing

Mandatory practice:

- Before tests or homework:

- Students explain answers orally

- Peer questions allowed

- Writing comes later

This instantly exposes rote learning.

Success marker:

Less copying, more hesitation—but better thinking.

- Replace Note Dictation with Note Making

Students write:

- “What I understood”

- “One example”

- “One doubt”

Marks not deducted for language errors.

Teacher role: Read for thinking, not handwriting.

PHASE 3: ASSESSMENT & PROJECT INTEGRATION (Months 7–9)

Goal:

Shift assessment from memory to reasoning.

- Monthly Mini-Projects (One per Class)

Examples:

- Why water levels change

- How prices are decided in the market

- How crops grow and fail

- How electricity reaches homes

Evaluation based on:

- Explanation

- Logic

- Participation

- Effort

No memorized speeches allowed.

- Open-Book / Open-Question Tests (Once per Term)

Questions like:

- Explain in your own words

- Give an example from village life

- Why do you think this happens?

Result:

Marks remain, but thinking improves.

- Teacher Peer Review Circles

Once a month:

- Teachers sit together

- Share what worked

- Share failures openly

Rule: No blaming, no inspection tone.

PHASE 4: CONSOLIDATION & CULTURE BUILDING (Months 10–12)

Goal:

Make change permanent, not personality-dependent.

- Student Reflection & Confidence Building

Students write or speak:

- What they can explain now

- What they still find hard

- What they enjoy learning

Confidence is the hidden metric.

- Parent Open Classroom Day

Parents observe:

- Oral explanations

- Group discussions

- Project displays

Seeing destroys resistance.

- School Learning Charter

Create a simple charter:

- How we teach

- How we assess

- How we treat mistakes

Display publicly.

This protects reform even if teachers transfer.

MEASURABLE OUTCOMES AFTER 1 YEAR

- Students speak more, copy less

- Teachers ask more questions than they answer

- Parents trust explanation over memorization

- Exam results remain stable or improve

- Dropout fear reduces

- Learning regains dignity

What This Plan Does NOT Promise

- Instant top ranks

- Zero syllabus pressure

- No exams

- Perfect English or handwriting

It promises something better:

Thinking children in a real village, facing real life, with real confidence.

How MEDA Foundation Can Support

MEDA Foundation can help rural schools with:

- Teacher training modules

- Context-based curriculum design

- Neurodiverse learner support

- Skill-to-employment linkages

Teacher Training Handbook

From Rote Learning to Learning by Understanding

A Practical Guide for Rural Schools in India

Conclusion First: What This Handbook Is Trying to Do

This handbook exists to liberate learning without breaking the school.

It is designed to help rural teachers move students out of rote learning and into understanding, without waiting for policy reform, expensive technology, or syllabus overhauls. The transformation proposed here is practical, low-cost, culturally grounded, and teacher-led.

At its heart, this handbook asserts a simple truth:

Rote learning is not a teacher failure. It is a system habit. Habits can be changed—systematically.

This handbook shows how.

It equips teachers to:

- Teach concepts, not pages

- Assess thinking, not memory

- Replace fear with curiosity

- Retain rigor without punishment

- Prepare students for life, not just exams

And it aligns directly with the mission of MEDA Foundation—creating inclusive, employment-linked, self-sustaining learning ecosystems, especially for rural and neurodiverse learners.

Why This Matters (Context & Crisis)

The Rural Reality

Rural schools face a triple constraint:

- Exam pressure without conceptual support

- Under-trained teachers carrying unrealistic expectations

- Parents equating marks with survival

Yet paradoxically, rural schools also have advantages:

- Smaller class sizes

- Community continuity

- Fewer distractions

- Strong oral traditions

This handbook leverages these strengths.

The Core Problem

Students are not failing because they lack intelligence.

They are failing because they are trained to repeat, not reason.

As Paulo Freire warned, when education becomes a “banking system,” students stop thinking and start memorizing to survive.

Intended Audience & Purpose

Intended Audience

- Primary and secondary school teachers

- Headmasters and academic coordinators

- NGO educators and volunteers

- Teacher trainers working in rural India

Purpose

- To retrain teachers without blaming them

- To shift classroom culture within one academic year

- To preserve exam performance while building understanding

- To create confident, curious, employable learners

Core Philosophy (Foundational Beliefs)

- Understanding precedes performance

- Fear kills learning faster than poverty

- Teachers are mentors, not content couriers

- Assessment must reveal thinking, not ranking

- Every child can think—if allowed

Section 1: The Teacher Mindset Shift

From Authority to Facilitator

Old Role | New Role |

Explains answers | Asks better questions |

Controls silence | Encourages dialogue |

Punishes mistakes | Uses mistakes diagnostically |

Rushes syllabus | Builds mental models |

Daily Practice:

- Speak 30% less

- Ask 3 open-ended questions per period

- Let students explain before correcting

Language That Changes Learning

Replace:

- “This will come in the exam”

With: - “Why do you think this works?”

Replace:

- “Wrong answer”

With: - “Interesting—how did you think about it?”

Section 2: Concept-First Teaching Framework

The 4-Step Lesson Structure

- Anchor (5 mins)

- Real-life story, local example, or problem

- Concept Discovery (15 mins)

- Question-led discussion

- Diagrams, objects, role-play

- Application (15 mins)

- New situation, not textbook repetition

- Reflection (5 mins)

- “What did we understand today?”

Example: Science (Photosynthesis)

- Anchor: “Why do plants near the well grow better?”

- Concept: Energy flow, sunlight, leaves

- Application: Predict growth in shade vs sun

- Reflection: Student explains in own words

Section 3: Questioning as a Teaching Skill

The Golden Rule

If the teacher is doing all the talking, learning is not happening.

Types of Questions

Type | Example |

Why | “Why does this happen?” |

How | “How would you test this?” |

What if | “What if we change this condition?” |

Explain | “Explain this to a younger child.” |

Weekly Target: Each teacher prepares 10 thinking questions per chapter.

Section 4: Assessment Without Fear

What to Stop Immediately

- Surprise tests

- Public shaming of marks

- Ranking on classroom walls

What to Introduce Gradually

- Open-Book Tests – test reasoning

- Oral Explanations – 2 minutes per student

- Concept Maps – draw connections

- Mini Projects – local problem-solving

Rigor Redefined:

Rigor = depth + transfer + clarity of thought

Section 5: Supporting Slow & Neurodiverse Learners

Key Insight

Slow learning is often deep learning delayed by fear.

Classroom Practices

- Allow verbal answers before written

- Pair learners strategically

- Use drawings and storytelling

- Reduce time pressure

Do Not Label. Do Not Compare.

Section 6: Teacher Collaboration Model

Weekly Teacher Circles (30 mins)

Agenda:

- One success story

- One classroom difficulty

- One student insight

No judgment. No inspection.

Section 7: Parent Engagement Guide

Parent Orientation Topics

- Why marks are not learning

- How understanding improves long-term success

- Mental health and confidence

Simple Message for Parents

“We are not reducing standards. We are raising thinking.”

Section 8: 1-Year Implementation Roadmap (Summary)

Quarter | Focus |

Q1 | Teacher mindset & questioning |

Q2 | Concept-first lessons |

Q3 | Assessment reform |

Q4 | Parent alignment & documentation |

Teacher Training Handbook – NIOS Focused

From Rote Learning to Learning by Understanding

Conclusion First: What This Handbook Enables

This handbook positions NIOS not as a fallback board, but as India’s most future-ready education framework—designed for learners who need flexibility, dignity, depth, and relevance. When used well, NIOS enables schools and teachers to move decisively away from rote memorization toward conceptual understanding, self-paced mastery, and real-world application.

NIOS is not weak where CBSE is strong. It is strong where CBSE is outdated.

Why NIOS Is Uniquely Suited for Learning by Understanding

NIOS already embodies many principles reformers struggle to introduce elsewhere:

- Self-paced learning

- Modular subject structure

- Tutor-facilitator model

- Multiple assessment windows

- Recognition of diverse learner journeys

Key Insight

NIOS fails only when it imitates conventional schooling. It succeeds when it embraces its original philosophy.

Intended Audience and Purpose

Audience:

- NIOS teachers, tutors, and facilitators

- Heads of Open Schooling Study Centres (AI/AVI)

- NGOs and civil society partners supporting NIOS learners

Purpose:

- To train teachers to use NIOS flexibility for deep learning

- To reposition NIOS classrooms as spaces of thinking, not coaching

- To restore learner dignity, especially for neurodiverse, working, rural, and non-linear learners

Section 1: Redefining the Role of the NIOS Teacher

From Instructor to Learning Guide

In NIOS, the teacher is not a syllabus enforcer but a learning architect.

Responsibilities shift from:

- Explaining everything → Designing learning pathways

- Completing portions → Ensuring conceptual clarity

- Policing attendance → Supporting learner autonomy

Gurukula Parallel: Acharya as mentor, not examiner.

Section 2: Understanding the NIOS Learner Profile

NIOS learners often include:

- School dropouts

- Working youth

- Neurodiverse learners

- First-generation learners

- Late bloomers

- Entrepreneurs and creatives

Hard Truth

These learners failed a system—not intelligence.

Teachers must replace judgment with diagnosis:

- What does the learner already know?

- Where is fear blocking learning?

- What pace suits this learner?

Section 3: Teaching for Concepts, Not Coverage (NIOS-Aligned)

Core Practice: One Concept, Multiple Expressions

For every topic:

- Explain orally

- Apply to real life

- Draw or map it

- Teach it to a peer

Example (Science – Force):

- Pushing carts

- Drawing force arrows

- Explaining friction in daily work

NIOS flexibility allows depth over speed—use it.

Section 4: Self-Paced Learning Without Isolation

Avoid the Biggest NIOS Risk: Loneliness

Self-paced does not mean unsupported.

Practices:

- Weekly discussion circles

- Peer explanation groups

- Mentor check-ins

- Learning journals

Rule: No learner should feel invisible.

Section 5: Assessment the NIOS Way (With Integrity)

Move Beyond Guess Papers and Coaching

Recommended methods:

- Open-book preparation sessions

- Oral reasoning checks

- Concept maps

- Portfolio evidence

- Reflection notes

Provocation: If assessment rewards memorization, NIOS becomes a coaching centre—not an education system.

Section 6: Reframing Certification and Dignity

Teachers must actively counter stigma:

- Speak proudly of NIOS certification

- Highlight alumni success stories

- Emphasize skill, thinking, and adaptability

Narrative Shift

NIOS is not an alternative for failures.

It is an alternative to rigidity.

Section 7: Working with Parents and Employers

Parent Education

- Explain flexible pacing

- Show thinking growth, not just marks

- Address fear of ‘mainstream loss’ honestly

Employer Engagement

- Showcase learner projects

- Emphasize skills and responsibility

- Build apprenticeship pathways

Section 8: Role of NGOs and MEDA Foundation

MEDA Foundation can support NIOS centres through:

- Teacher training and mentoring

- Learning-by-doing modules

- Neurodiverse learner inclusion

- Skill-to-employment bridges

Strategic Advantage: NIOS + Civil Society = Scalable reform without policy paralysis.

Section 9: 90-Day Teacher Action Plan (NIOS)

- Month 1: Shift questioning style

- Month 2: Introduce learner journals

- Month 3: Pilot portfolio assessment

Small changes, consistently applied, transform learning culture.

Closing Reflection

NIOS was designed for freedom—but freedom without guidance becomes neglect.

When NIOS teachers reclaim their role as mentors, facilitators, and thinkers, the system becomes what it was always meant to be: education for real life, not rank lists.

NIOS Subject-wise Sample Lessons

Concept-First, Context-Rooted, Exam-Compatible

Conclusion First: What These Lessons Achieve

These sample lessons demonstrate how NIOS subjects can be taught for understanding first and examination success second—without increasing cost, time pressure, or syllabus deviation. Each lesson is designed to:

- Start from lived reality

- Build core concepts deeply

- Encourage explanation before memorization

- Remain fully NIOS-exam compatible

This is Gurukula wisdom applied through modern open schooling.

How to Use These Lessons

Each lesson follows a common structure:

- Core Concept

- Real-Life Anchor (Rural / Indian context)

- Teacher Facilitation Guide

- Learner Activities

- Understanding Checks (Non-rote)

- Exam Alignment

Teachers may adapt pace and language based on learner profiles.

SUBJECT 1: MATHEMATICS

Lesson: Understanding Fractions (Secondary Level)

Core Concept

A fraction represents a relationship, not a number to memorize.

Real-Life Anchor

Dividing land, sharing rice, splitting wages, ration distribution.

Teacher Facilitation

- Ask: “If 1 acre is divided among 4 people, what does each get?”

- Draw land divisions on the floor or board.

Learner Activities

- Physically divide objects (paper, food items)

- Draw fraction models

- Explain fraction meaning orally

Understanding Checks

- Why is 1/2 bigger than 1/3?

- Can 2/4 and 1/2 be the same? Why?

Exam Alignment

Covers representation, simplification, comparison of fractions.

SUBJECT 2: SCIENCE

Lesson: Evaporation and Condensation

Core Concept

Matter changes state due to energy transfer.

Real-Life Anchor

Drying clothes, water droplets on steel plates, steam from cooking.

Teacher Facilitation

- Observe wet cloth drying

- Ask learners to predict outcomes

Learner Activities

- Daily observation journal

- Draw water cycle locally

- Explain process to peers

Understanding Checks

- Why do clothes dry faster in summer?

- Why do lids drip water?

Exam Alignment

States of matter, change of state, heat transfer.

SUBJECT 3: SOCIAL SCIENCE

Lesson: Panchayati Raj System

Core Concept

Decentralized governance enables local decision-making.

Real-Life Anchor

Village panchayat meetings, local dispute resolution.

Teacher Facilitation

- Invite discussion on village issues

- Map governance hierarchy

Learner Activities

- Role-play Gram Sabha

- Identify panchayat responsibilities

Understanding Checks

- Why can’t all decisions be taken by the central government?

- What happens if local bodies fail?

Exam Alignment

Civics chapters on democracy and governance.

SUBJECT 4: LANGUAGE (Hindi / English / Regional)

Lesson: Storytelling for Comprehension

Core Concept

Language is a tool for meaning-making, not rule-following.

Real-Life Anchor

Folktales, family stories, local events.

Teacher Facilitation

- Narrate a short story

- Ask learners to retell in their own words

Learner Activities

- Oral retelling

- Change ending of story

- Identify emotions and intentions

Understanding Checks

- Why did the character act this way?

- What would you do differently?

Exam Alignment

Reading comprehension, writing skills, grammar in context.

SUBJECT 5: ECONOMICS / BUSINESS STUDIES

Lesson: Demand and Supply

Core Concept

Prices change due to availability and need.

Real-Life Anchor

Vegetable prices, festival demand, crop seasons.

Teacher Facilitation

- Discuss recent price changes

- Draw simple demand-supply curves

Learner Activities

- Market observation

- Interview local vendor

- Explain price fluctuation

Understanding Checks

- Why do onion prices rise suddenly?

- Who benefits when supply falls?

Exam Alignment

Basic economic concepts and diagrams.

SUBJECT 6: ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES

Lesson: Water Conservation

Core Concept

Resources are finite and interconnected.

Real-Life Anchor

Borewells, tanks, monsoon cycles.

Teacher Facilitation

- Local water mapping

- Discuss past vs present availability

Learner Activities

- Household water audit

- Propose conservation ideas

Understanding Checks

- Why is groundwater declining?

- How does individual action matter?

Exam Alignment

Environmental awareness, sustainability topics.

SUBJECT 7: LIFE SKILLS / WORK EDUCATION

Lesson: Decision-Making

Core Concept

Good decisions balance information, values, and consequences.

Real-Life Anchor

Spending money, choosing work, handling conflict.

Teacher Facilitation

- Present real dilemmas

- Encourage multiple solutions

Learner Activities

- Role-play scenarios

- Reflect on past decisions

Understanding Checks

- What made a decision good or bad?

- Can right decisions still fail?

Exam Alignment

Employability skills, personal development modules.

Closing Reflection

Concept-first teaching does not dilute academic rigor—it reclaims it. When NIOS teachers anchor learning in lived reality and guide learners to explain ideas, education becomes durable, transferable, and dignified.

Closing Reflection

Rote learning is not the enemy—fear is.

Fear of failure.

Fear of non-conformity.

Fear of falling outside an imposed rank order that mistakes comparison for competence.

Fear is a powerful but corrosive motivator. It produces short-term compliance and long-term fragility. It trains learners to seek approval rather than understanding, safety rather than truth. Over time, fear narrows curiosity, silences questions, and teaches young minds that being wrong is more dangerous than being shallow. This is not an accident of the system; it is one of its most predictable outcomes.

India’s civilizational strength has never rested on fear-based conformity. It rested on śraddhā (trust in learning), viveka (discernment), and abhyāsa (patient practice). The Gurukula did not motivate learners through threat or ranking, but through meaning, belonging, and purpose. Understanding was not rushed; wisdom was not standardized; dignity was not conditional.

When education replaces fear with understanding, something profound shifts. Marks lose their tyranny. Certificates stop pretending to be character references. Learning regains its rightful place as a humanizing force, not a sorting mechanism. Students stop asking, “Will this come in the exam?” and start asking, “What does this mean, and how should I live with it?”

This is the transformation India urgently needs—not incremental reform, but restorative reform. A return to first principles expressed through modern forms. An education system that produces thinkers instead of test-takers, citizens instead of credential-holders, and contributors instead of competitors trapped in zero-sum races.

Participate and Donate to MEDA Foundation

This vision will not realize itself through policy documents alone. It requires ground-level experimentation, patient institution-building, and moral courage.

MEDA Foundation is actively working to build inclusive, self-sustaining learning ecosystems, with a special focus on neurodiverse learners and those excluded by rigid credentialism. Through teacher training, learner-centric models, skill-to-employment pathways, and community-rooted initiatives, MEDA is piloting education that works in the real world—not just on paper.

Your participation, collaboration, and donations directly support:

- Teachers who want to teach for understanding, not just coverage

- Learners who do not fit standardized molds but carry immense potential

- Education models that restore dignity, relevance, and self-reliance

Civilizations are not renewed by intentions alone. They are renewed by people who choose to act.

Book References

- Pedagogy of the Oppressed – Paulo Freire

- How Children Fail – John Holt

- Deschooling Society – Ivan Illich

- Mindstorms – Seymour Papert

- The End of Average – Todd Rose

If this article resonated with you, consider it an invitation—not merely to agree, but to participate. Education reform is not someone else’s responsibility anymore. It is ours.