Designed for everyday cooks, students, families, and anyone trying to eat better without spending more, it speaks to people who sense they are throwing away nutrition along with peels and stems but feel unsure what is safe or worthwhile. It is especially useful for budget-conscious households, urban kitchens with limited time, and readers curious about traditional food wisdom without wanting extreme rules. By clearly separating what can be eaten directly, what needs processing, and what should be discarded, it saves effort, protects digestion, and builds confidence. Readers gain practical ways to stretch food, reduce waste, support gut health, and make choices rather than following trends or guilt.

Why This Guide Exists

Food is becoming more expensive, yet many diets remain nutritionally thin. At the same time, large portions of edible plant matter are routinely discarded—not because they lack value, but because modern kitchens have lost the knowledge, confidence, or time to use them well. This creates a quiet contradiction: spending more on food while extracting less nourishment from it.

Much of the nutrition loss happens before food reaches the plate. Peels, stems, skins, and seeds often contain fiber, minerals, and protective compounds, but are removed by habit rather than informed choice. Traditional food cultures approached these parts with discernment—using some regularly, some occasionally, and avoiding others—without turning frugality into strain or ideology.

The purpose here is simple: help readers get more value from what they already buy. Not by forcing consumption, but by offering clarity, safety, and practical judgment.

How to Use This Guide (Decision-First Framework)

The purpose of this guide is not to encourage eating everything indiscriminately, but to help you decide wisely. Every peel, stem, or seed does not deserve a place on the plate. Good decisions come from asking the right questions before acting, not after discomfort or wasted effort.

The Three Questions to Ask First

1. Is it traditionally consumed somewhere?

Traditional use is the first and strongest safety filter. Foods that have been eaten repeatedly across regions and generations have undergone a kind of long-term human testing. For example, watermelon rind is commonly used in Rajasthani cooking (tarbooj ki sabzi), ridge gourd peel appears in South Indian thogayals, and jackfruit seeds are cooked and eaten across eastern and southern India. In contrast, mango peel has very limited culinary use in Indian traditions and is more often associated with irritation, indicating caution rather than neglect.

2. Does it need processing to be safe or digestible?

Many plant parts are edible only after the right preparation. Banana stem is a classic example—it is nutritious but fibrous and must be finely chopped, soaked, and thoroughly cooked. Sesame seeds with their skin are mineral-rich, but without dry roasting and grinding, much of their nutrition remains inaccessible. Bitter bottle gourd is another critical example: when bitterness appears, no processing makes it safe—it must be discarded entirely.

3. Does the nutrition justify the effort?

Not all edible parts are worth daily attention. Citrus peel contains valuable flavonoids, but requires drying, grinding, and small-dose use. This makes it an occasional addition, not a staple. On the other hand, cauliflower stalks and leaves offer fiber and minerals and can be easily chopped into regular sabzi, making them high return for low effort.

A Simple Safety Ladder (With Indian Examples)

1. Safe Raw With Washing

These can be eaten with minimal intervention once properly washed.

Cucumber peel

Carrot peel

Tomato skin and seeds

Tender coriander stems

These provide mostly insoluble fiber and mild phytonutrients and suit regular consumption.

2. Safe After Normal Cooking

These require basic cooking to become digestible and beneficial.

Potato skin (non-green, well-washed)

Cauliflower stalks and leaves

Pumpkin peel

Ridge gourd peel

Cooking softens fibers and reduces irritation while retaining minerals.

3. Safe Only After Specific Processing

These are valuable but demand correct technique.

Banana stem (soaking + cooking)

Jackfruit seeds (boiling or roasting)

Sesame seeds (dry roasting + grinding)

Citrus peel (drying, powdering, or marmalade)

Here, processing unlocks nutrients and prevents digestive stress.

4. Not Worth the Effort

Edible in theory, but nutritionally or practically inefficient.

Very thick citrus pith in large quantities

Mature okra stems

Tough onion skins (beyond broth use)

These may be composted without regret.

5. Must Be Discarded

These pose real health risks and should never be “experimented” with.

Green potato skin and sprouts

Bitter bottle gourd

Spoiled or fermented vegetable peels with off smells

No nutritional gain justifies the risk here.

Core Principle to Remember

Traditional diets never aimed to consume everything. They aimed to use what made sense, at the right time, in the right quantity, with the right preparation. This framework restores that judgment, helping you eat more wisely—not more aggressively.:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/uses-for-leftover-fruit-and-vegetable-peels-4863542copy-ca255d1fe43141e7b46cb7cc9c07f5dc.jpg)

First Principles: Safety, Source, and Digestion

Before increasing the use of peels, stems, seeds, or skins, three fundamentals must be clear: where the food comes from, how it is cleaned, and how the body handles it. Ignoring these basics turns a good intention into a digestive or health burden.

Organic vs Conventional: What It Really Changes

Organic produce generally carries a lower pesticide load, which makes eating peels and skins more reasonable—but not automatically safe. Organic does not mean unwashed, and conventional does not mean unusable. For hard-skinned vegetables like pumpkin, bottle gourd, or banana, peeling reduces exposure regardless of farming method. For soft peels such as apple, tomato, or cucumber, sourcing matters more. The key shift is not blind trust in labels, but adjusting usage: peels from conventionally grown produce may be used occasionally or after cooking, while those from trusted sources can be used more regularly.

Proper Washing Methods That Actually Help

Washing removes surface dirt, microbes, and some residues—not all chemicals. A practical approach is soaking vegetables for 10–15 minutes in clean water, followed by firm scrubbing under running water. Salt or vinegar soaks help loosen grime and reduce microbial load, but they are not detox solutions. Peels should never be eaten from produce that smells off, feels slimy, or shows mold, regardless of washing.

Antinutrients vs Toxins vs Irritants

These are often confused, but they are very different. Antinutrients (like phytates in grain bran or oxalates in some leaves) reduce mineral absorption but are manageable through soaking, cooking, or fermentation. Irritants cause digestive or skin discomfort—mango peel is a common example—and tolerance varies by person. Toxins, such as solanine in green potatoes or compounds in bitter bottle gourd, are non-negotiable and must be avoided entirely. No preparation makes them safe.

Quantity and Frequency Matter More Than Novelty

Using more of a food does not mean using it every day. Traditional diets rotated peels and fibrous parts seasonally and in small amounts. Citrus peel, sesame skin, or banana stem can be beneficial occasionally but become counterproductive when overused. The aim is not to add more elements to each meal, but to integrate them sensibly over time, respecting digestion and context rather than chasing novelty.

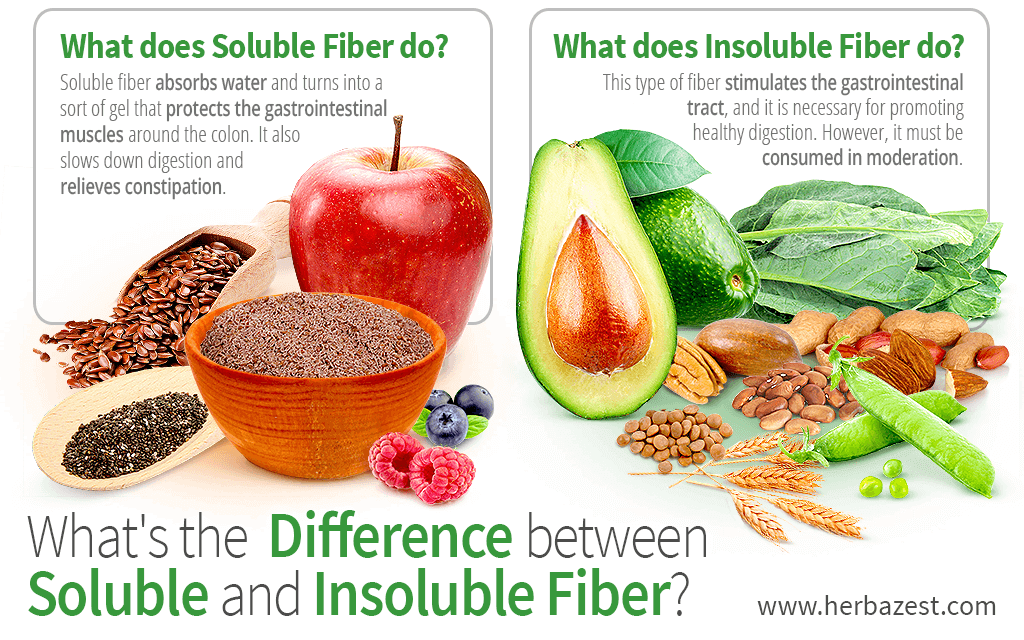

Fibre Matters: Soluble vs Insoluble (And Why It Changes Usage)

Fibre is often spoken of as a single nutrient, but how it behaves in the body depends on its type. Understanding the difference between insoluble and soluble fibre explains why some peels feel “rough,” others feel “slimy,” and why preparation methods matter as much as the food itself.

A. Insoluble Fibre–Heavy Parts

(Bulk, Gut Motility)

Insoluble fibre does not dissolve in water. It passes through the digestive tract largely intact, adding bulk to stool and helping move waste along.

Common Indian examples

Vegetable peels: potato, carrot, cucumber

Stems: cauliflower stalks, broccoli stems

Grain bran: wheat bran, rice bran

What it does

Increases stool volume

Speeds up bowel movement

Promotes fullness by physically occupying space

Why preparation matters

Insoluble fibre is structurally tough. Raw or poorly cooked forms can irritate the gut, especially for people with sensitive digestion. Cooking softens plant cell walls, reducing mechanical stress. Adding fat—such as oil, ghee, or coconut—helps lubricate digestion and improves tolerance. Adequate water intake is essential; without it, high insoluble fibre can worsen constipation rather than relieve it.

Practical example

Cauliflower stalks finely chopped and cooked into sabzi are easier to digest than grated raw stalks in salads. Potato skins roasted with oil are better tolerated than boiled skins eaten plain.

B. Soluble Fibre–Rich Parts

(Gut Bacteria, Sugar Control)

Soluble fibre dissolves in water to form a gel-like substance. This slows digestion and acts as food for beneficial gut bacteria.

Common Indian examples

Citrus pith (white inner layer)

Apple peel

Banana stem

Okra

What it does

Slows glucose absorption, stabilising blood sugar

Binds bile acids, helping regulate cholesterol

Feeds gut microbes, producing short-chain fatty acids

Why preparation matters

Soluble fibre becomes more effective—and gentler—when hydrated. Soaking, cooking, or fermentation allows it to swell and form gels that protect the gut lining. Raw intake may cause bloating or discomfort, especially in large amounts.

Practical example

Okra releases mucilage when cooked, which helps regulate blood sugar. Banana stem must be soaked and cooked to release soluble fibre without causing digestive strain. Citrus pith works best when slow-cooked into marmalade or dried and used sparingly.

Key Insight

Insoluble fibre moves things through the gut. Soluble fibre slows things down and feeds bacteria. Both are valuable, but they serve different roles. Using the wrong type, in the wrong form, or in excess leads to discomfort. Balanced diets succeed not by maximising fibre, but by matching type, preparation, and quantity to the body’s needs.

Parts That Can and Should Be Consumed Directly (With Normal Cooking)

Not all peels, stems, and seeds require elaborate preparation. Many parts are safe, nutritious, and easy to include with everyday cooking. Incorporating them wisely helps increase fibre, minerals, and phytonutrients while stretching your food budget.

A. Vegetable Peels & Stems

These are generally high in insoluble fibre, minerals, and some antioxidants. When tender and properly washed, they can be cooked like the rest of the vegetable.

Potato (non-green, thin-skinned): Provides potassium, fibre, and B-vitamins. Peel after washing or scrub gently; avoid green or sprouting parts. Roasting or boiling with skin keeps nutrients intact.

Carrot: Skin contains beta-carotene and fibre. Scrub instead of peeling completely. Works well in stir-fries, stews, or parathas.

Ridge gourd, bottle gourd (tender): Soft outer skin is edible; adds fibre and vitamins. Ideal for light stir-fries, stews, or thogayals.

Cauliflower leaves and stalks: Leaves are rich in calcium and iron; stalks contain fibre and antioxidants. Chop finely and add to curries, khichdi, or mixed vegetable dishes.

Broccoli stems: Contain fibre and vitamin C. Peel the outer fibrous layer if tough, then cook or stir-fry. Grated stems can be added to parathas or soups.

Tip: Even fibrous stems become digestible and palatable when chopped finely, lightly cooked, or combined with fat.

B. Seeds Naturally Meant to Be Eaten

Some seeds are already designed for consumption and can be used along with the fruit or vegetable pulp.

Tomato seeds: Rich in fibre, potassium, and antioxidants. They are soft and easily digestible, so no removal is necessary.

Pumpkin seeds (tender inside the fruit): Contain protein, magnesium, and healthy fats. Roast lightly with a pinch of salt for enhanced flavour.

Bottle gourd seeds (young): Small and tender, provide additional fibre and micronutrients. Use in curries or soups where the seeds soften during cooking.

Key Principle: These parts deliver high return for minimal effort. They are easily integrated into regular cooking and add nutrition without significant extra work. Avoid forcing parts that are tough, bitter, or otherwise unsafe—focus on what is naturally edible with simple washing and normal cooking.

Traditional & Global Recipes Where “Scraps” Are the Star

Using peels, stems, seeds, and other “discarded” parts doesn’t have to feel like a compromise. Across cultures, many dishes celebrate these parts as primary ingredients, showing that what we often throw away can be both flavorful and nutritious. These recipes provide practical inspiration for incorporating scraps in a way that is safe, tasty, and culturally validated.

A. Indian Regional Wisdom

Rajasthani Tarbooj ki Sabzi (Watermelon Rind): The tender inner rind is cooked with spices and oil, creating a subtly sweet, lightly spiced curry. It is hydrating, rich in fibre, and stretches the summer fruit further.

Ridge Gourd Peel Thogayal (South India): The thin peel is sautéed with spices, lentils, and coconut to make a concentrated, flavourful chutney that pairs with rice or idli.

Banana Stem Curry / Usili: Chopped banana stem is simmered with lentils and spices, providing fibre, potassium, and a unique texture. Common in South Indian homes as a post-festive or cooling dish.

Kumro’r Khosa Bhaja (Pumpkin Peel – Bengal): Pumpkin peel is pan-fried or sautéed with mild spices. It delivers fibre and antioxidants, making it a regular accompaniment in Bengali meals.

Jackfruit Seed Curry: Seeds are boiled or roasted, then cooked with spices. Rich in resistant starch and protein, they are a versatile ingredient in curries or snacks.

B. Global Examples

Citrus Marmalade (Mediterranean): Entire fruit, including peel, is cooked slowly with sugar to make a tangy preserve, unlocking flavonoids and antioxidants in the pith and peel.

Fried Potato Skins (UK/Ireland): Potato skins are crisped with seasoning or baked into chips, retaining fibre and minerals that would otherwise be discarded.

Pickled Vegetable Peels (Japan): Peels from daikon, cucumber, or carrot are pickled, creating a tangy, probiotic-rich side dish.

Apple Peel Vinegar (Eastern Europe): Apple peels are fermented with sugar and water to produce vinegar, concentrating nutrients and supporting gut health.

Key Insight

The success of these dishes comes from treating peels, seeds, and stems as central ingredients, not afterthoughts. Proper technique—washing, cooking, fermentation, or roasting—makes them palatable, safe, and nutritionally valuable. When approached this way, scraps stop being waste and start being a source of flavour, fibre, and micronutrients.

When Taste Is the Barrier: Managing Bitter, Grassy, Fibrous Notes

Even when a peel, stem, or seed is safe and nutritious, taste or texture can prevent regular use. Many discarded parts are naturally bitter, fibrous, or “grassy”, which can be off-putting. Fortunately, simple techniques and cooking methods can transform them into delicious, digestible additions to everyday meals.

A. Simple Techniques

Fine Chopping – Smaller pieces reduce chewiness and help the flavour blend with the rest of the dish. For example, finely chopped cauliflower stalks or ridge gourd peel integrate seamlessly into curries or parathas.

Salt Rest and Rinse – Lightly salting tough or slightly bitter vegetable parts for 10–15 minutes and rinsing removes excess water, reduces bitterness, and softens texture. Works well for bitter melon rind or banana stem.

Acid Addition (Lemon, Tamarind, Curd) – Acid balances bitterness and brightens flavour. A squeeze of lemon over cooked ridge gourd peel or adding tamarind pulp to pumpkin peel stir-fry makes the dish more palatable.

Fat Pairing (Ghee, Oil, Coconut) – Fat coats fibres, improves mouthfeel, and carries flavour. Cooking insoluble fibrous parts like cauliflower stalks or carrot peel with ghee or coconut oil softens texture and reduces “dry” chewiness.

B. Cooking Methods That Help

Dry Roasting Before Grinding – Seeds, peels, and spices can develop a nutty flavour while losing harshness. Roasting pumpkin or sesame seeds before grinding unlocks aroma and reduces bitterness.

Pressure Cooking for Stalks – Dense stems, like banana stem or broccoli stalks, become tender quickly under pressure, reducing chewiness and releasing natural sweetness.

Tempering to Add Umami – Mustard seeds, curry leaves, dried chilies, or cumin tempered in oil can transform bland or slightly bitter vegetable peels into flavourful accompaniments. For example, tempering ridge gourd peel thogayal with cumin and coconut adds depth without overpowering.

Key Insight:

Taste challenges can be solved without compromising safety or nutrition. By combining size, acidity, fat, and heat, even the toughest, fibrous, or bitter parts of vegetables and fruits can become delicious, digestible, and regularly usable.

Parts Better Processed Separately (Occasional Use)

Some peels, seeds, and other parts are nutritionally valuable but require special handling before they can be consumed safely or enjoyed. Processing them separately—not mixing them casually into everyday cooking—ensures maximum nutrient release, palatability, and safety. These techniques are worth the effort occasionally rather than daily.

A. Peels

Banana Peel (Boiled, Minced) – Banana peels are fibrous and slightly bitter raw. Boiling softens the fibres, reduces bitterness, and allows them to be minced into curries, stir-fries, or cutlets, adding fibre, potassium, and polyphenols.

Citrus Peel (Dried, Powdered) – Citrus peel contains flavonoids, antioxidants, and trace minerals. Drying and grinding it into powder concentrates these nutrients and allows small, controlled use in desserts, marmalades, or spice blends.

Ridge Gourd Peel Chutneys – Cooking and grinding ridge gourd peel with spices and lentils creates a flavourful chutney. The peel’s tough texture and mild bitterness are balanced, while nutrients like fibre, vitamin C, and antioxidants are preserved.

B. Seeds

Pumpkin and Watermelon Seeds (Washed, Dried, Roasted) – Seeds contain protein, magnesium, and healthy fats but may be tough and slightly bitter raw. Roasting enhances flavour and digestibility while making them snack-ready or suitable for powders and spice blends.

Jackfruit Seeds (Boiled or Roasted) – Dense seeds require cooking to remove antinutrients and improve digestibility. Boiling or roasting softens them, making them suitable for curries or snacks rich in resistant starch and protein.

C. Fermentation & Drinks

Ginger Bug from Ginger Skin – Ginger peels, often discarded, can be used to start a probiotic ferment (“ginger bug”). This produces a mildly fizzy, nutritious base for homemade sodas and gut-friendly drinks.

Fruit Peel Ferments (Small, Controlled Batches) – Citrus, apple, or pineapple peels can be fermented to make vinegar or probiotic drinks. Controlled fermentation unlocks bioactive compounds while preventing spoilage.

Key Insight:

Special processing—boiling, roasting, drying, fermenting—turns tough, bitter, or fibrous parts into nutritionally rich, edible components. These methods are not everyday steps but occasional enhancements that make the most of food that would otherwise go unused.

Grains, Legumes, Lentils & Seeds: Using Skins Wisely

Beyond vegetables and fruits, grains, lentils, legumes, and seeds also have parts that are often discarded—bran, husks, and skins. These components are nutrient-dense, containing fibre, minerals, and antioxidants. However, their digestibility and bioavailability vary, so understanding preparation methods is key.

A. Whole Grains & Bran

Examples: Rice bran, wheat bran, millets with husk intact

Benefits: Bran is rich in insoluble fibre, B-vitamins, and minerals such as magnesium and iron. It improves digestion, supports gut microbiota, and adds satiety.

Digestive Limits: Raw bran is very fibrous and can cause bloating or gas if consumed in large quantities. Gradual integration is advised.

Preparation Tips:

Soaking grains overnight reduces phytic acid, improving mineral absorption.

Fermentation (idli, dosa batter, sourdough) activates enzymes, making bran nutrients more bioavailable.

Sourdough or sprouting techniques further unlock micronutrients, enhance digestibility, and reduce antinutrients.

B. Lentils & Legumes With Skins

Examples: Whole masoor, whole moong, chickpeas with skins intact

Nutritional Value: Skins provide fibre, antioxidants, and some protein.

Preparation Tips:

Soaking softens skins and reduces cooking time.

Pressure cooking ensures even cooking and breaks down fibre, making it easier to digest.

Sprouting vs skin removal: Sprouting enhances nutrient availability and enzyme activity. Skin removal may be necessary for people with sensitive digestion, but nutrient loss occurs. Choosing depends on digestive tolerance vs nutritional maximization.

C. Seeds With Skins (e.g., Sesame)

Examples: Black sesame (with skin), white sesame

Benefits: Skin contains minerals like calcium, iron, and magnesium; also rich in lignans.

Processing Tips:

Dry roasting activates flavour and increases mineral availability.

Grinding with a little salt or fat (ghee, sesame oil) enhances absorption and integrates into chutneys, laddus, or curries.

Black sesame retains more phytonutrients due to skin; white sesame is milder but slightly less nutrient-dense.

Key Insight:

Grains, lentils, and seeds often hold hidden nutrition in their skins, but only when prepared correctly. Soaking, cooking, sprouting, roasting, or fermenting ensures digestibility and nutrient uptake, while raw consumption of fibrous husks may cause discomfort. Thoughtful preparation converts “discarded” parts into high-value dietary components.

Parts Best Avoided or Discarded

Not all peels, stems, and seeds are safe, digestible, or worth the effort. Some contain toxins or irritants, while others are simply too fibrous, bitter, or labor-intensive to make eating them worthwhile. Knowing what to leave behind is as important as knowing what to use.

A. Due to Toxins or Irritants

These parts can cause real health risks if consumed and should never be experimented with:

Green potato skin & sprouts: Contain solanine, a natural toxin that can cause nausea, vomiting, or neurological symptoms.

Bitter bottle gourd: Contains cucurbitacins, which are highly toxic when bitterness is present. Even small amounts can cause severe stomach upset.

Mango peel: Often irritant due to urushiol-like compounds; can cause rashes or digestive discomfort.

Rhubarb leaves: Contain oxalic acid at toxic levels, causing kidney and digestive issues.

Raw cassava peel: Contains cyanogenic glycosides, which are toxic unless properly processed.

Tomato leaves/stems: Contain alkaloids that can irritate the gut if eaten in quantity.

Bitter melon seeds (unripe or overly mature): Can be harsh on the digestive system.

B. Due to Poor Return on Effort

Some parts are safe but require significant work for minimal nutritional benefit:

Very thick citrus pith (large amounts): Extremely fibrous and bitter; better for small doses like marmalade or zest.

Mature okra stems: Tough, woody, and low in digestible nutrients.

Onion outer skin (beyond broth use): Hard, fibrous, and not palatable.

Garlic cloves with papery skins: Not toxic, but taste and texture are unpleasant unless used in broth.

Corn husks (for humans, not tamales): Too fibrous to eat; nutrients are minimal compared to effort required to cook them.

Cucumber thick skin of certain varieties: Very bitter and fibrous; only thin layers are worth using.

Key Insight:

Avoiding harmful or impractical parts is as important as using nutritious scraps. Safety, digestibility, and effort-to-nutrition ratio should guide decisions, ensuring that integrating peels, seeds, and stems adds value rather than risk.

Special Considerations

Using peels, stems, seeds, and other “scraps” is not one-size-fits-all. Individual factors—age, digestion, and lifestyle—determine what is appropriate, how often, and in what form.

Children, elderly, and sensitive digestion: Tough peels, fibrous stalks, or highly bitter parts may irritate or be hard to chew. Prioritise soft, cooked, or processed forms, and introduce slowly. Banana stem curry or finely chopped cauliflower stalks are usually well-tolerated in moderate amounts.

When to prioritise digestibility over fibre: Insoluble fibre is valuable, but in people prone to constipation, bloating, or gut sensitivity, softening via cooking, soaking, or roasting is better than forcing raw intake.

Seasonal and climatic alignment: Some parts are cooling (ridge gourd peel, cucumber skin), others warming (ginger skin infusions). Align use with climate, health, and body constitution for optimal benefit.

Is It Worth It? A Reality Check

Not all peels or seeds deserve your effort. A practical evaluation helps decide when to invest energy and when to skip.

Worth It When:

The scrap replaces store-bought items (e.g., citrus peel for marmalade or ginger bug for probiotic drinks)

There is a cultural precedent validating safety and palatability (e.g., tarbooj ki sabzi, ridge gourd thogayal)

Parts can be batch-prepped for efficiency (drying citrus peel, roasting seeds)

Skip When:

Digestive cost is high (fibrous, bitter, or tough parts causing bloating or discomfort)

Processing is fuel-, time-, or labour-heavy with minimal gain (very thick citrus pith, mature okra stems)

Nutritional return is marginal compared with the effort or risk

Key Insight:

Maximizing food value is about smart, selective use, not extreme consumption. Focus on parts that deliver nutrition, flavour, and convenience, and gracefully let go of those that do not. This approach balances health, time, taste, and sustainability.

Final Takeaway

Using more of your food is a skill, not a rule. It’s about understanding what adds value, what requires processing, and what is best left out. Traditional kitchens teach us balance—how much to use, how often, and in what form—without forcing consumption or creating strain.

Composting or repurposing peels, seeds, and stems is not failure—it’s completion. When something cannot be eaten, it can still nourish your garden, home, or body in other ways.

Eat fully, wisely, and without stress, focusing on safety, digestibility, and practicality.

Support Meda Foundation

This article, like all others, has been possible due to the support of patrons. If you have found it informative or useful, consider donating. Additionally, share your knowledge and experiences via the feedback form.

Resources for Further Research

National Institute of Nutrition, India – Food Composition Tables

ICAR – Indian Council of Agricultural Research: Post-Harvest & Food Processing

DIY Fermented Drinks: Ginger Bug & Fruit Peel Ferments – Cultures for Health

Nutritional Insights on Vegetable Stalks & Leaves – ResearchGate